Bereaved Parents Experiences of Hospital Practices and Staff Reactions after the Sudden Unexpected Death of a Child

Received: 01-Jan-1970 / Accepted Date: 01-Jan-1970 / Published Date: 20-Feb-2018 DOI: 10.4172/1522-4821.1000385

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to examine the experiences of bereaved parents and caregivers, who experienced a sudden unexpected infant or child death, an infant death attributed to Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) or a child death attributed to Sudden Unexplained Death in Childhood (SUDC), with hospital practices and staff upon the child’s arrival at the emergency department. A convenience sample of 139 parents, caregivers and guardians responded. Data collected were descriptive and narrative. Narrative data was analyzed using phenomenological qualitative analyses. The study addressed the parents’ experience with: the ambulance service, contact with professionals, information received about procedures, access to or holding the child, extended family’s access to the child, perceived respect and support of the hospital staff, obtaining keepsakes or the child’s belongings and the parent’s aftercare instructions upon leaving the hospital. Implications to improve or revise current hospital procedures are discussed.

Keywords: Sudden infant death syndrome; Hospital policies; Bereaved parents; Staff reaction

Introduction

Each year in the United States roughly 3,500 children reportedly die a sudden and unexpected death classified under Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) or other ill-defined and unspecified causes of mortality (ICD R99) (Centers for Disease Control, 2018). SIDS and Sudden Unexpected Infant Death (SUID) are diagnoses of exclusion and considered when an infant, under the age of 1 year, has died suddenly and unexpectedly and the autopsy, examination of the death scene and a review of the clinical history provide little explanation to the cause of death leaving the death ultimately unexplained (Centers for Disease Control, 2018). There remains another subset of sudden and unexpected deaths in childhood, referred to as Sudden Unexplained Death in Childhood (SUDC), that typically occur in children over the age of 1 year old, and much like SUID and SIDS deaths, the cause of death goes unexplained after a thorough case investigation. The rate of deaths is approximately 1.5 deaths per 100,000 children, with most of these deaths occurring in children ages 1 to 4 years old. In 2016, there were 236 toddler deaths in the United States classified as ill-defined or unknown causes of mortality (Sudden Unexplained Death in Childhood, 2018).

In many sudden and unexpected child death cases, the child is brought to the emergency department by way of caregiver or ambulance, whereas a much smaller number of children are pronounced and remained at the scene (Rudd, Capizzi-Marain & Crandall, 2014). Unlike more common reasons for sudden child deaths, such as drowning or accidents, children later identified as SIDS, SUID or SUDC come to the emergency department with no easily identifiable cause for the presenting symptoms. Therefore, hospital personnel are tasked with not only providing life-saving measures to the child, but balancing the caregiver’s grief and ensuing requests that can include requesting to be with or hold the child, and the local medicolegal death investigative practices.

Hospital practices regarding the family’s access to the child or honoring the family’s requests are often informed by, or completed in conjunction with, the county’s coroner or medicolegal death investigative practices. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) published a policy statement in 2014 outlining best practices when there is a death of a child in the emergency department. The policy suggests departments follow a patientcentered approach with compassion and respect for families. The AAP recommends health care teams provide parents with information on the child’s condition and resuscitation attempts, medical or hospital protocols impacting the family’s experience, available support service available at the hospital and community support resources. Furthermore, in 2016 the U.S. Department of Justice’s National Committee on Forensic Science released their view regarding the medico-legal death investigative practices. They suggest investigators should make or allow all reasonable attempts to provide caregivers time with their child, information on the investigative process, and a timeline for procedures including the autopsy and other measures. However, families experience of the death investigation practices continues to be widely varied across the United States depending on the emergency department, agency and jurisdiction (Drake, Cron, Giardino, Trevino, & Nolte, 2015; Posey & Neuilly, 2017).

Regardless of the cause of death, hospital personnel are tasked with the supporting bereaved families, many without clear guidelines for best-practices (Field & Behrman, 2003; Rudd, Capizzi-Marain & Crandall, 2014). Additionally, due to the unexpected nature of these deaths, hospitals must also comply with the county’s corner and local law enforcements death investigative protocols which in some cases may conflict with the family’s wishes (Department of Health and Human Services, 2007). Therefore, the responsibility is relegated to emergency room staff to meet the conflicting requirements of all involved after the sudden and unexpected death of a child. The purpose of this study was to examine the experiences of caregivers with hospital procedures and staff after the sudden and unexpected death of their child.

Methods

Design and Collection

This study was specifically interested in the experiences, opinions and frequencies of events for parents bereaved by a sudden unexplained death and whose child was taken to the emergency room. A survey research design was chosen. A convenience sample of parents, grandparents or guardians who lost a child under the age of 18 due to a sudden and unexpected death was obtained through three organizations: Sudden Unexplained Death in Childhood (SUDC) Foundation, The CJ Foundation for SIDS and First Candle. Participants were asked to complete a 20-minute multiple choice and narrative fill-in survey created in an online survey software program. The survey was developed to identify the experiences of participants with hospital personnel and procedures including the policies of the medicolegal death investigative process while at the hospital, the experiences with medical staff, access to their child and their child’s belongings and opinion of perceived support from those involved. The invitation to participate in the survey was made via e-mail communications from the three major support organizations. The data was collected over a three-month period. Inclusion criteria were restricted to a parent, grandparent or guardian whose child was taken into the emergency room and pronounced dead. These individuals are referred to as caregiver in this article. Also, the child’s death was ultimately ruled undetermined, unexplained or lacked evidence to substantiate the final cause of death. This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Hackensack University Medical Center IRB.

Data Analysis

Data collected was both descriptive and narrative. Descriptive data was analyzed by identifying number of participants for each category and percentage of the total scores. Furthermore, qualitative data was also obtained which allowed participants to expand upon their answers. The qualitative data was analyzed using phenomenological analysis. The first author read the narrative data for each question independently. This was completed two times and then the first author summarized each statement in the column of the paper. After this step was completed the first author went through the list of summarized statements and identified statements of similar meaning or intent. The author developed theme title to summarize the essence of these statements. Once this step was completed the author went back through the narrative data to ensure accuracy of the theme identified. Themes were weighted according to frequency (i.e., “witnessing resuscitation attempts were helpful” (f=5) and used to inform descriptive data.

Participants

A total of 139 participants responded to the survey and of those, 7 were male and 132 were female. 118 identified as the parent to the child who died, 21 identified as the grandparent, and 1 identified as the guardian. Of the children who died, 84 were male and 55 were female. A total of 30 children died between ages 0-2 months, 45 children died between the ages of 3-5 months, 7 between the ages of 6-9 months, 9 between 10-12 months, 17 between 13-17 months, 14 between 18-23 months, and 15 between 2 and 4 years, 2 between 5-9 years, and no deaths reported between 10-13 years and 14-18 years old. Furthermore, the cause of death was later determined as follows: 29 due to SUDC, 64 due to SIDS, 7 positional asphyxiation, 5 asphyxiation due to overlay, 1 to gastric asphyxiation, 4 to bronchopneumonia, and 1 to each of the following: overwhelming enterovirus, suspected seizure, Influenza B, septic shock from E Coli infection, reactive airway disease and bilateral adrenal hemorrhage.

Results

In addition to the descriptive data, several themes emerged from qualitative analysis which provides useful information on the varied experiences of the bereaved and their suggestions for professionals.

Transportation to Hospital

When asked if caregivers rode in the ambulance with the child the results were varied. A total of 21.1% (24) of caregivers had requested to ride in the ambulance to the hospital but were not permitted. One mother reported “They did not let me (the mother) ride in the ambulance with my baby nor did they know which hospital they were going to right away-they argued about which hospital to go to in front of me.” 21.9% (25) did not ride in the ambulance but did not ask to do so. While over 40% of caregivers had to use his or her own transportation to the hospital, 15.8% (18) caregivers were allowed to sit in the front of the ambulance and 4.4% (5) were able to sit next to his or her child.

Professional Contacts

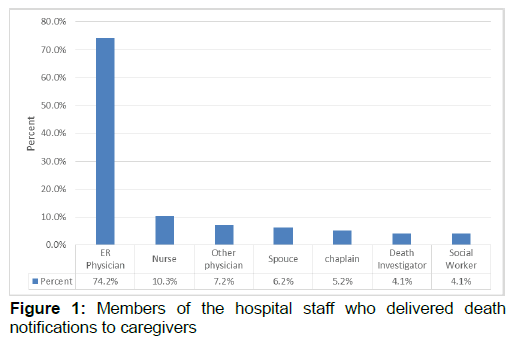

Once at the hospital, caregivers met with numerous hospital staff. The most frequent contacts with staff members were nurses 85% (96) and ER Physicians 85% (96). 66.1% (n=72) of caregivers were asked if they wanted a spiritual or religious advisor called (i.e., Clergy, chaplain or rabbi), and only 56.6% (n=64) of the total number of participants received that service. A lower number of caregivers reported contact with a hospital social worker (35.4%, n=40) and only 33% (n=36) had a social worker assigned to their family. Additionally, families had the lowest amount of contact with hospital physicians (31%, n=35). However, a few caregivers reported no contact with hospital staff or doctors (f=4). One parent shared “Our experience was terrible. We were left alone, no one explained anything. No one offered to get a social worker or chaplain.” Regardless of the contact-types with hospital staff, overwhelmingly caregivers were provided the death notification by the ER physician, however, some received this information from other staff (see Figure 1). Some families reported a team of professionals provide the death notification. Whereas other families were present for resuscitation attempts and present when the time of death was called (f=11), therefore did not receive a formal death notification from staff.

Information

The caregivers surveyed had never experienced a sudden, unexpected and ultimately, unexplained death of a child. They felt unfamiliar with policy and procedure related to the medico-legal investigative process. 49.5% (n=54) of the caregivers received information from the medical staff about what was happening and 10.1% (n=11) received written information on the autopsy and autopsy procedure. Furthermore, some caregivers reported that communication was key. Any shared information on what was done to their child, explanation of any life saving techniques that were used, or even being present for resuscitation was helpful (f=2). This was further validated by caregivers who expressed negative experiences because of not being told what was happening, or not informed of procedures or hospital and death investigative policies (f=7). One parent reported “we felt very uniformed. I know that the medical staffs were hard working to save my baby, but if I had known how close to death he was I would have demanded more time with him.”

Holding the Child

The range of experiences at the hospital undoubtedly vary for each family, but it was important to identify the frequency at which some experiences, identified in the literature as positive to the grief process, occurred for SUID, SIDS and SUDC families. Most caregivers were allowed to touch their child (92.6%, n=100). 76.1% (n=83) of caregivers were allowed to hold their child and of that percentage, 74.3% (81) were allowed to hold the child unsupervised, whereas 33.9% (n=37) were allowed to hold the child under supervision of a professional. In many cases resuscitation attempts were made therefore medical equipment was still attached to the child’s body. Some caregivers (f=3) noted it was helpful when the nursing staff removed medical equipment, bathed the child or wrapped the child in a warm blanket prior to the caregivers’ time with the child. Only 4.6% (n=5) of caregivers were given the opportunity to bathe their child. A caregiver shared “they were wonderful! After he was pronounced, they removed all resuscitation equipment, bathed him and wrapped him in a warmed blanket. They dimmed the lights and brought in a rocking chair.” A few caregivers (f=3) detailed negative experiences when the child’s body was not prepared, or they were not briefed on the child’s condition. Nevertheless, caregivers wanted to see their child and demonstrated regret if they were not given or did not take that opportunity. Ten caregivers expressed appreciation that hospital staff allowed them private time with the child and helped the family remain comfortable. One caregiver shared “the nurses offered to help make telephone calls, provided tissues and water and a private area.” Another caregiver shared “they were very courteous, they gave us time and space. They brought in coffee and Danishes.” Often in busy hospitals privacy and space are hard to come by, but 74.3% (n=81) reported privacy to be with their child. Some parents reported a negative experience (f=8) such as feeling rushed by hospital staff. One caregiver shared “they would not let me stay and hold my baby as long as I needed too.”

In many cases, extended family came to the hospital to support the newly bereaved family. Many respondents reported that hospital staff asked if they could contact family for the newly bereaved (32.1%, n=35). A total of 78% (n=85) immediate family members were allowed by hospital staff to see the child, whereas only 61.5% (n=67) of extended family able to see the child.

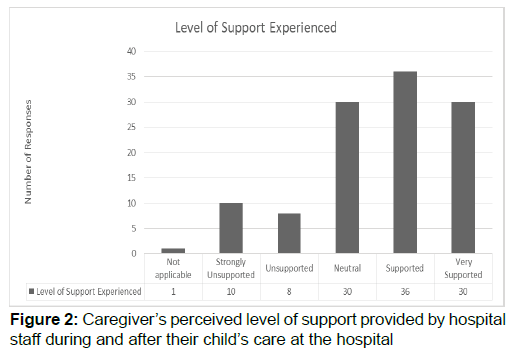

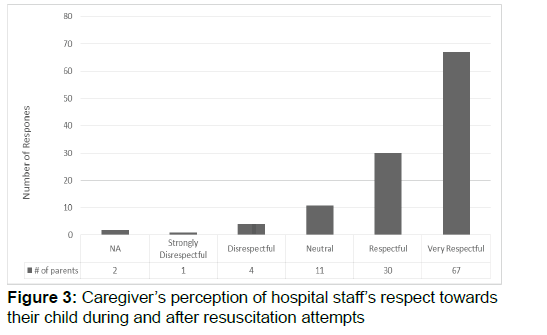

Perceived Respect

One area of interest was the caregiver’s perception of perceived support and respect from hospital staff (see Figure 2) Caregivers overwhelmingly reported their appreciation for the staffs’ compassion, respect and attention provided to the newly bereaved (f=23). One parent wrote “upon first arriving at the hospital a nurse stayed with me the entire time explaining everything that was going on.” Caregivers also shared their appreciation for the staff’s sympathy (f=7). One parent shared “we had an amazing team of professionals that cared for us and even cried with us.” On the other hand, parents who reported negative experiences believed those staff were inept, too emotional or too insensitive (f=12). A parent shared “by the time we got the hospital, they needed her room apparently and put her-on her gurney in a room that was being used [as a] storage closet. We saw her, touched her and said goodbye next to a stack of supply boxes-we felt this was very disrespectful.” Another parent shared “one inconsiderate nurse said ‘don’t worry, you’re young and can try again’ while I rocked my newly deceased infant.” The majority of participants, believed the care shown to their child by professionals was “very respectful” (Figure 3).

Child’s Belongings and Keepsakes

Upon leaving the hospital it is not uncommon for caregivers to want his or her child’s belongings such as clothes or other items that may have traveled with the child to the hospital. When caregivers were asked if items were returned the majority of caregivers noted the items were collected by the police and/or investigators (35.7%, n=41). A total of 31.3% (36) of caregivers did not receive the child’s belongings and 30.4% (35) of caregivers did. Of those caregivers who were asked by hospital staff if they wanted to take the child’s belongings 1.7% (2) of caregivers did not. Furthermore, 1 (0.9%) caregiver was able to take the items home but had to initiate the request. In addition to the child’s belongings only 40.4% (n=44) of caregivers were provided a memorial keepsake box (i.e., footprints, handprints, locket of hair). Two parents stated they were thankful a keepsake was provided. A parent stated, “really a blur I do remember them taking a piece of her hair and a foot print which was super nice and they wrapped her in a special blanket.” Five caregivers noted they would have liked to take a keepsake home but was not given an option. One parent stated “the hardest part for me was leaving empty handed. There’s a box at the hospital in the nursery for stillbirth but ours was the first SIDS case they had encountered so nothing was offered to us as far as keepsakes and we had to leave empty handed. I still feel bitter about that.”

Aftercare

Caregivers came to the hospital with little to no knowledge regarding hospital protocol after a sudden and unexpected death, the medico-legal death investigative process, or grief resources after such deaths. Only 40.4% (n=44) of caregivers reported leaving the hospital with grief information or follow-up resources. Four caregivers provided narrative comments on the lack of information received. One caregivers shared “wish there was more support afterwards – no follow up, no grief packet, didn’t know where to turn or what to even do next.” Only 15.6% (n=17) of our caregivers stated they received follow-up from hospital staff after leaving the hospital. Some caregivers provided narrative feedback expressing disappointment that promises made by the hospital staff, or requests made to the hospital by the family were not ultimately followed through by hospital personnel. A parent shared “I had to talk the hospital staff to get the plaster casts they made of my son’s hand and foot…. for nearly one month and got 101 reasons why they didn’t ‘get them done.’ I had to email hospital administration because I felt put off.”

Discussion

While these sudden and unexpected infant and child deaths are not frequently encountered in emergency departments, they do occur. The various factors unique to these deaths such as: the age of the child, the sudden and unexpected nature, the potential for traumatic reactions from family and caregivers, and ways polices regarding death investigation may contradict the needs of the family may all pose a unique challenge to hospital personnel. It is imperative that hospitals have policies in place which not only meet to the needs of the death investigation but also consider the needs of these families. Standardized procedures can go a long way in supporting parents through this process.

Undoubtedly caregivers will encounter a variety of different hospital and emergency department personnel upon arrival at the ER, and these professionals will understandably focus all their efforts on saving the life of the child. However, after all resuscitation efforts have ceased and/or death is pronounced, it is important that a designated hospital physician or nurse follow-up with the family regarding what resuscitation attempts were made (If the family was not present), answer any questions the family may have about the child’s death and explain the purpose of the autopsy and autopsy procedures. Additionally, an assigned hospital staff should be the point of contact for the family and ensure the family has adequate time with the child and answer any follow-up questions.

Over half of those who participated in this study did not receive information on the policies and procedures typically enacted when a child comes to the emergency department. This time is not only stressful, but emotional for these families. Knowing what one can expect, the procedures their child will endure, who will be their point of contact, and what they can expect will go a long way to comfort a family through a very difficult experience. Additionally, hospital staff should consider providing information on the autopsy and autopsy procedure as many families often are unaware of this policy or what it entails.

The majority of our participants were allowed to see or touch their child at the hospital. However, the quality and nature of this time varied greatly among our participants. Some caregivers were able to hold their child unsupervised while others were only allowed to touch their child with supervision present. Caregivers and family members expressed appreciation for the invitation to not only be with their child after death, but to be given a private space with ample time to be with their child. Hospital and death investigative staff should weigh the family’s desire and wishes to hold the child with the death investigative process. The opportunity to spend time holding and being with the child appears to have a lasting meaningful and memorable impact for these parents and should be strongly considered.

Participants of this study were overwhelmingly pleased with the level of perceived respect, compassion, and attention their child received in the emergency department and overall felt positively supported by hospital staff. This suggests that current patientcentered or family-centered care practices are making a big impact on these families.

Many hospitals with maternal wards have policies and procedures in place to support parents after the death of a fetus such as keepsake boxes which include footprints, handprints or lockets of hair. Emergency departments may consider offering this service to these caregivers especially if the materials and policies are in place. When caregivers become bereaved suddenly and unexpectedly they do not often think to request keepsakes or even know such options exist. Hospital staff can create a memorable and priceless memento for these caregivers to take with them when they leave.

Understandably, the emergency department is focused on patient care and saving lives and is not intended provide long-term aftercare to grieving families-or in these cases, even providing discharge instructions. However, caregivers may benefit from receiving aftercare instructions to include: contact information for the coroner or medical examiner’s office, the purpose of the autopsy and suggested timeline for procedures and results, grief or bereavement support services in their community, and if the investigative procedures do not allow for keepsake boxes to be made, suggestions on working with the funeral home or mortuary to receive these keepsakes. These inexpensive and simple gestures have potential for immense impact and subsequent gratitude for these grieving families.

While the majority of caregivers were satisfied and pleased with the care their child received, and the perceived level of support and respect received by hospital staff, there remained and alarming number of cases which suggest hospitals can do more to support newly bereaved families. Hospitals and emergency departments would benefit from development or adoption of policies and procedures on how to support bereaved families after an unexpected child death. The American Academy of Pediatrics (2014) published a policy statement regarding bestpractice approaches for supporting bereaved families in the emergency department while also adhering to guidelines for the forensic evaluation. The recommendations set forth by the AAP are reinterred by the families in this study suggesting emergency departments would be well served by formalizing such procedures.

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics. (2014). Policy statement: Death of a child in the emergency department. Centers for Disease Control. (2018). Underlying Cause of Death, 1999-2016. Drake, S. A., Cron, S. G., Giardino, A., Trevino, V., & Nolte, K. B., (2015). Comparative analysis of the public health role of two types of death investigation systems in Texas: Application of essential services. J Forensic Sci, 60(4), 914-918. Department of Health and Human Services. (2007). Infant death investigation: Guidelines for the scene investigator. Sudden, unexplained infant death investigation. Field, M.J., & Behrman, R.E., (2003). When children die: Improving palliative and end-of-life care for children and their families. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. Posey, BM., & Neuilly, MA., (2017). A fatal review: Exploring how children’s deaths are reported in the United States. Child Abuse & Neglect, 72, 433-445. Rudd, R., Capizzi-Marain, L., & Crandall, L., (2014). To hold or not to hold: Medicolegal death investigative practices used during unexpected child death investigations and the experiences of next of kin. ‎Am J Med Pathol, 35, 132-139. Sudden Unexpected Death in Childhood. (2017). Statistics. United States Department of Justice. (2016). National Committee on Forensic Science: Views of the commission communication with next of kin and other family members.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 7316

- [From(publication date): 0-2018 - Jun 30, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 6345

- PDF downloads: 971