Research Article Open Access

Beyond Primary Care: Integrating Psychiatry into a Certified Home Health Agency to Identify and Treat Homebound Older Adults with Mental Disorders

Ceïde ME, Nguyen SA, Korenblatt A and Kennedy GJ*

Montefiore Medical Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine Bronx, NY, USA

- *Corresponding Author:

- Gary J Kennedy

Professor and Vice Chair for Education; Director of Division of Geriatric Psychiatry and Fellowship Program

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Montefiore Medical Center

Albert Einstein College of Medicine, USA

Tel: +1 718 920 4236

Fax: +1 718 920 6538

E-mail: GKENNEDY@montefiore.org

Received date: September 01, 2016; Accepted date: October 07, 2016; Published date: October 24, 2016

Citation: Ceïde ME, Nguyen SA, Korenblatt A, Kennedy G (2016) Beyond Primary Care: Integrating Psychiatry into a Certified Home Health Agency to Identify and Treat Homebound Older Adults with Mental Disorders. J Community Med Health Educ 6:479. doi: 10.4172/2161-0711.1000479

Copyright: © 2016 Ceïde ME, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Community Medicine & Health Education

Abstract

Introduction: The purpose of this study was to determine if the Montefiore Home Care (MHC) Geriatric Psychiatry Program (MHC-GPP) increases access to mental health care and appropriate management as evidenced by timeliness of psychiatric evaluation, patient acceptance of the intervention, communication of diagnoses and recommendations to primary care physicians (PCPs) and rate of medical hospitalization. Methods: 178 MHC patients’ charts were reviewed. The time from social work referral to initial psychiatric evaluation was calculated as well as how many patients were agreeable to pharmacological intervention at the time of assessment. The rate of 30-days and 60-days hospitalization from the date of the in-home geriatric psychiatric evaluation to inpatient medical hospitalization was calculated. A group of 95 patients with Montefiore Medical Center (MMC) PCPs were sampled from the original 178. The percentage of new mental disorders diagnosed by the psychiatrist was collected and the percentage of primary care physicians who continued to prescribe the recommended pharmacologic intervention at 6 months follow-up. Results: In terms of timeliness of psychiatric evaluation, 13% were seen the same day, 46% of patients were evaluated within one week of referral. 92% of patients were agreeable to pharmacological intervention at the time of evaluation. In regards to the risk of hospitalization, 16% of patients were admitted to a within 30 days of psychiatric evaluation. An additional 9% were admitted within 60 days of evaluation. 78% of the new diagnoses were a neurocognitive disorder. At 6 months follow-up 59% of PCPs were prescribing and titrating the recommended medication. Conclusion: The MHC-GPP has successfully increased access to mental health evaluation and treatment for this unrecognized and undertreated population for the past 12 years.

Keywords

Homebound older adults; Behavioral integration; Home care

Background

The purpose of this paper is to describe a model of behavioral integration that goes beyond primary care to access homebound older adults by co-locating a geriatric psychiatrist into a Certified Home Health Agency (CHHA) and collaborating with primary care physicians (PCPs) and Managed Long Term Care Providers (MLTC). 20% of older adults have a mental health need but only 3% of them will seek care from a mental health specialist [1]. In addition, minority older adults tend to report worse mental health status, more disability and poorer access to mental health services as compared to their Non- Hispanic White counterparts [2,3]. This lack of access to mental health services is particularly concerning given the cost of untreated mental illness. Meta-analyses have found that untreated depression was associated with more frequent medication noncompliance [4], amplifies the morbidity of chronic physical diseases like sleep apnea and diabetes [5,6] and is associated with a 43% increase risk of allcause mortality [7]. Conversely studies have found physical ailments like diabetes and heart failure are associated with an increased prevalence of depression [8,9].

To address the increased prevalence of mental disorders in medically ill patients and poor access to mental health care, models of behavioral integration have been developed. The most notable is the multicenter randomized control trial, Improving Mood-Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment (IMPACT) collaborative care management program [10,11]. In this model of integration, a depression care manager provides psychoeducation and support, while the primary care provider (PCP) prescribes antidepressant therapy and the social worker provides psychotherapy. The psychiatrist provides supervision and consultation for complex cases. In adults 60 years and older, the IMPACT model yielded more satisfaction with depression care, lower depression severity, less functional impairment, and improved quality of life at 3, 6, and 12 months follow-up [11,12]. Another collaborative care trial, Primary Care Elderly: Collaborative Trial (PROSPECT) demonstrated that depression care management mitigated the increased mortality associated with depression in medically ill older adults [13]. Other models of integration include colocation, in which the mental health specialist sees the patients in the same setting as the PCP. Although this model is less cost effective in large settings, it may work well in smaller settings like home care agencies [14].

Although mental health integration in primary care settings has been successful, frail or homebound older adults may be unable to engage these programs. Among homebound elders, the prevalence of mental disorders doubles to 40%, of which 28% is depression [15]. The increase in prevalence maybe due to the presence of multiple chronic illnesses, cognitive impairment and poor social support [15,16]. One House Calls for Seniors Program found that 31.9% of elders have 4 or more medical illnesses and 53% of patients had a Mini Mental Status Exam score of 23 or less [17]. Other risk factors for mental disorders in homebound older adults include lower education level, less financial resources, and trauma history [18]. Based on the overwhelming evidence that homebound older adults are more depressed, more cognitively impaired, more medically ill and have more psychosocial stressors than their ambulatory counterparts, an interprofessional home-based approach working in collaboration with PCPs, is promising.

For example, Montefiore Medical Center (MMC) has 20 years of experience as a Care Management Organization (CMO) and was chosen to be the only Pioneer Accountable Care Organization (ACO) in New York State in 2012. Within the MMC health network, 9% of ACO beneficiaries incur 55% of the medical cost. 55% of this high risk population has a mental health diagnosis. In order to improve the quality of care, improve health outcomes, and reduce unnecessary health care expenditures, MMC has introduced numerous initiatives to integrate mental health specialists into nontraditional medical settings. These models of integration include collaborative care, colocation and psychiatric hospitalist programs.

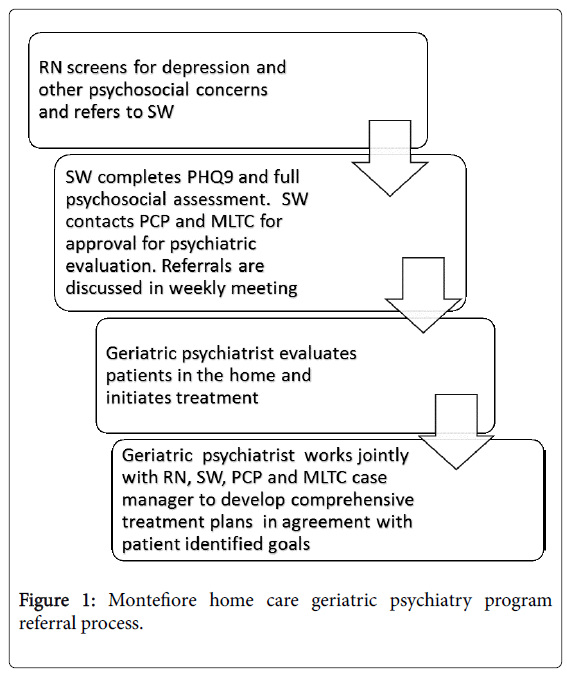

In 2004, Montefiore Home Care (MHC) in collaboration with the MMC Department of Psychiatry with funding from the United Jewish Appeal established an innovative program to identify and treat homebound older adults with depression known as the Montefiore Home Care Geriatric Psychiatry Program (MHC-GPP). Weill Cornell Medical College led by Martha Bruce, PhD, MPH who has extensive experience in training home care nurses to screen for depression [19] provided education and training on how to screen for depression using the Patient Health Questionnaire 2 (PHQ-2) [20,21] in the home care Outcome and Assessment Information tool (OASIS). The home care social workers were trained to administer the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9) [22]. Home Care nurses can refer patients with a PHQ-2 of 3 or more or other concerning psychiatric symptoms to the home care social work department. The MHC-GPP team consists of the geriatric psychiatrist, the director of home care social work and the home care social workers who provide the initial comprehensive screening. Referrals are discussed in a weekly conference and appropriate cases are evaluated by the psychiatrist in the home (Figure 1). Unlike the collaborative care model, the psychiatrist in the MHC-GPP initiates pharmacological treatment immediately and transitions care to the PCP or a mental health clinic for follow-up. The psychiatric evaluation and recommendations are shared with the home care team including the social worker and nurse, the PCP and the Managed Long Term Care (MLTC) manager via encrypted email and electronic health record (EHR).

The purpose of this study is to describe the MHC-GPP and identify trends towards increases access to mental health care and provides appropriate management as evidenced by timeliness of psychiatric evaluation, patient acceptance of the intervention, communication of diagnoses and recommendations to PCPs and rate of medical hospitalization.

Material and Methods

We reviewed patient charts for 178 MHC patients referred to the MHC-GPP consecutively from June 2013 to September 2014 to provide descriptive data. Patient information is documented in two separate electronic health records (Allscripts® and CareCast®). Using the EHR, gender, ethnicity, psychiatric diagnoses and recommendations were collected. The time from social work referral to initial psychiatric evaluation was calculated to assess timeliness of intervention. We calculated how many patients were agreeable to pharmacological intervention at the time of assessment. Next the rate of 30-days and 60-days hospitalization from the date of the in-home geriatric psychiatric evaluation to inpatient medical hospitalization was calculated. This was compared with the Montefiore Home Care (MHC) risk of 30 days re-hospitalization score. The MHC risk score is a validated scale using 26 risk factors gathered from the OASIS [23]. The scores range from 1 to 16; a higher score signifies an increased risk of 30-day readmission after a hospitalization.

In order to assess the ability of the MHC-GPP to identify previously unrecognized mental disorders, the percentage of new mental disorders diagnosed by the psychiatrist was collected. Of the original 178 charts reviewed, 95 patients with MMC PCPs were sampled from the original 178. The percentage of new mental disorders diagnosed by the psychiatrist was collected in order to assess the ability of the MHCGPP to identify previously unrecognized mental disorders. To assess the effectiveness of the communication between the MHC-GPP psychiatrist and the PCP, the percentage of PCPs who continued to prescribe the recommended pharmacologic intervention at 6 months follow-up was also calculated. Prescribing was defined as refilling the medication and mentioning the medication in the treatment plan.

Results

Table 1 displays the baseline demographics of the 178 patient charts reviewed; the majority of patients were 70 years old or older. The majority of patients served by the program were Hispanic or Non- Hispanic Black. This is consistent with Bronx County census data from 2015 showing a population of 55% Hispanic and 43% Non-Hispanic Black [24].

| Variables | Value (N) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| 60-70 | 26% (46) |

| 71-80 | 34% (60) |

| 81 and older | 35% (62) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 26% (47) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 49% (88) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 30% (54) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 18% (32) |

Table 1: Demographics N=178.

In terms of timeliness of psychiatric evaluation, 13% were seen the same day, 46% of patients were evaluated within one week of referral, and 28% were seen within 2 weeks. 109 patients out of 178 received a recommendation for pharmacological intervention, 92% of which were agreeable to pharmacological intervention at the time of evaluation.

In regards to the risk of hospitalization, the most prevalent risk factors for 30 days re-hospitalization are illustrated in Table 2. The mean MHC risk score was 7 which is associated with 22% risk of 30 days re-hospitalization [23]. 16% of patients were admitted to a medical hospital within 30 days of psychiatric evaluation. An additional 9% were admitted within 60 days of evaluation.

| Risk Factors | Value (N) |

|---|---|

| Medical Comorbidities | |

| Three or More Diagnoses | 81.6% (142) |

| CHF | 14.4% (25) |

| Diabetes | 46.0% (80) |

| Obesity | 13.2% (23) |

| Medical Related Factors other than disease process | |

| Confusion | 13.2% (23) |

| DC From Hosp | 16.1% (28) |

| Polypharmacy (5 or more meds) | 75.9% (132) |

| History of Falls | 14.4% (25) |

| High risk of Falls | 68.4% (119) |

| Med Management Issues | 67.2% (117) |

| Multiple Hospitalizations | 31.0% (54) |

| Social Risk Factors | |

| Support Network Issues | 57.5% (100) |

| Low Socio Economic | 60.9% (106) |

*MHC Risk Score is calculated by giving 1 point for each risk factor. Only factors with prevalence over 10% were included in table.

Table 2: Patient risk factors for hospitalization.

Of the 95 patient charts reviewed with MMC PCPs, 52% of them received a new mental disorder diagnosis following psychiatric consultation. Table 3 shows the percentage of new diagnoses made. Of note 78% of the new diagnoses were a neurocognitive disorder (Alzheimer’s, Vascular Dementia, Cognitive Disorder NOS, or Mild, Moderate, to Severe Cognitive Impairment). Also 64% (N=61) of patients were started on a psychotropic medication. At 6 months follow-up, PCPs were prescribing and titrating the recommended medication in 59% (N=31) of patients.

| Variable | %(N) |

| Neurocognitive Disorders | 78% (38) |

| Mood Disorders | 45% (22) |

| Substance Use Disorders | 14% (7) |

| Other | 4% (4) |

Table 3: Percentage of new diagnoses N=95.

Conclusion

We have described a model of behavioral integration utilizing colocation in a CHHA to provide mental health services to homebound older adults who would not be able to engage in primary care based interventions. Based on the descriptive data above, the MHC-GPP serves and older population with multiple medical illnesses and psychosocial stressors. Our findings suggest that the program design allows for timely evaluation, with the majority of cases seen within 2 weeks of referral. Despite a diverse population with a majority Hispanic and Non-Hispanic Blacks, two groups that traditionally do not accept psychiatric treatment [25,26], over 90% were agreeable to psychotropic intervention. This is striking, suggesting that behavioral integration programs may reduce health disparities by increasing access to mental health care in a non-stigmatized setting. In addition the MHC-GPP minimized unnecessary 30 days medical hospitalization for a high risk population of home care patients. While 16% of 30 days medical hospitalization may appear high, Medicare data from 2011 found a rate as high as 29% in home care patients [27]; suggesting our program significantly minimized the 30 days hospitalization rate compared to CHHA patients in general.

Our findings also demonstrate that the MHC-GPP identified mental disorders that had previously been unrecognized by the PCP, especially neurocognitive disorders. This highlights the poor recognition of mild and moderate cognitive impairment by PCPs likely due to a number of factors including limited time and lack of reporting of cognitive complaints by caregivers. In a cross sectional study of PCPs, mild dementia was missed 90% of the time and moderate dementia was missed 50% of the time [28] Using the colocation model of integration in which the psychiatrist initiates pharmacological treatment, our study also found that almost over half of PCPs were still prescribing and titrating the recommended medication. Furthermore, past studies have found that PCPs initiate medications like antidepressants but often do not adjust to an effective dose, even when poor response is noted [29].

Our findings have several limitations, however. Firstly, the MHCGPP is available to all patients but it has not been assess in a randomized controlled clinical trial. Specifically, we can extrapolate that we have a lower than expected 30 days hospitalization rate but we did not compare to historical controls or other home care patients who did not receive the intervention. In terms of patient acceptance of treatment, actual medication compliance was not track over time. It is possible that patients agreed to interventions but later did not adhere to recommendations. We also did not track patients’ responses to treatment over time. In addition while our diverse population is strength this may limit the generalizability of our findings to nonurban settings with few ethnic minorities. However, in terms of medical morbidities, our population is consistent with Certified Home Health Agency (CHHA) patients in other cities. Finally, as described in Tables 1 and 2, our patient population is medically and socially complex. They receive care in from multiple providers, making it challenging to determine if our interventions are changing outcomes.

While this study identified trends in patient outcomes further analysis is warranted. Future analysis of the MHC-GPP cohort will include identifying aged matched Montefiore Home Care controls and preforming multivariate regression analysis to identify risk factors for medical hospitalization. Future directions of our program will include following patient outcomes possibly by repeating the PHQ9 prior to discharge from the CHHA. As many of the patients served by the MHC-GPP are CMO recipients and MLTC recipients, tracking hospitalizations over time and health care utilization for patient’s prior to the MHC-GPP and then after made the program interventions. In terms of quality improvement, future plans include expanding the MHC-GPP team to provide in-home psychotherapy for depressed and anxious patients with and without cognitive impairment. We also plan to deepen our collaboration with the MLTC and work closely with care management to identify patients with depression and/or cognitive impairment who are higher health care utilizers [27,30].

In summary, homebound older adults particularly those receiving services from a CHHA, have a high prevalence of mental disorders including depression and cognitive impairment [15,16]. The Montefiore Home Care Geriatric Psychiatry Program has successfully increased access to mental health evaluation and treatment for this unrecognized and undertreated population for the past 12 years. This model highlights the strength of colocation as a model of integration when coupled with collaboration across a health system [14]. As behavioral integration becomes the norm in psychiatry it is important to think beyond primary care. Home care services are a unique avenue to bring behavioral care to underserved populations.

References

- Directors CfDCaPaNAoCD (2008) The state of mental health and aging in america issue brief 1: what do the data tell us? National association of chronic disease directors, Atlanta, GA, pp: 1-12.

- Ng JH, Bierman AS, Elliott MN, Wilson RL, Xia C, et al. (2014) Beyond black and white: race/ethnicity and health status among older adults. Am J managed care 20: 239-248.

- Sorkin DH, Pham E, Ngo-Metzger Q (2009) Racial and ethnic differences in the mental health needs and access to care of older adults in california. J Am Geriatrics Society 57: 2311-2317.

- DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW (2000) Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med 160: 2101-2107.

- Lustman PJ, Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, de Groot M, Carney RM, et al. (2000) Depression and poor glycemic control: a meta-analytic review of the literature. Diabetes care 23: 934-942.

- Ceide ME, Williams NJ, Seixas A, Longman-Mills SK, Jean-Louis G (2015) Obstructive sleep apnea risk and psychological health among non-Hispanic blacks in the Metabolic Syndrome Outcome (MetSO) cohort study. Ann med 47: 687-693.

- Saint Onge JM, Krueger PM, Rogers RG (2014) The relationship between major depression and nonsuicide mortality for U.S. adults: the importance of health behaviors. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 69: 622-632.

- Koenig HG (1998) Depression in hospitalized older patients with congestive heart failure. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 20: 29-43.

- Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ (2001) The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes care 24: 1069-1078.

- Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, Williams JW Jr, Hunkeler E, et al. (2003) Depression treatment in a sample of 1,801 depressed older adults in primary care. J Am Geriatr Soc 51: 505-514.

- Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, Williams JW Jr, Hunkeler E, et al. (2002) Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 288: 2836-2845.

- Williams JW Jr, Katon W, Lin EH, Noel PH, Worchel J, et al. (2004) The effectiveness of depression care management on diabetes-related outcomes in older patients. Ann Intern Med 140: 1015-1024.

- Gallo JJ, Hwang S, Joo JH, Bogner HR, Morales KH, et al. (2016) Multimorbidity, depression, and mortality in primary care: randomized clinical trial of an evidence-based depression care management program on mortality risk. J Gen Intern Med 31: 380-386.

- Weiss M, Schwartz BJ (2013) Lessons learned from a colocation model using psychiatrists in urban primary care settings. J Prim Care Community Health 4: 228-234.

- Wang J, Kearney JA, Jia H, Shang J (2016) Mental Health Disorders in Elderly People Receiving Home Care: Prevalence and Correlates in the National U.S. Population. Nurs Res 65: 107-116.

- Qiu WQ, Dean M, Liu T, George L, Gann M, et al. (2010) Physical and mental health of homebound older adults: an overlooked population. J Am Geriatr Soc 58: 2423-2428.

- Beck RA, Arizmendi A, Purnell C, Fultz BA, Callahan CM (2009) House calls for seniors: building and sustaining a model of care for homebound seniors. J Am Geriatr Soc 57: 1103-1109.

- Cohen-Mansfield J, Shmotkin D, Hazan H (2010) The effect of homebound status on older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 58: 2358-2362.

- Brown EL, Raue PJ, Roos BA, Sheeran T, Bruce ML (2010) Training nursing staff to recognize depression in home healthcare. J Am Geriatr Soc 58: 122-128.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB (2003) The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Medical care 41: 1284-1292.

- Li C, Friedman B, Conwell Y, Fiscella K (2007) Validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire 2 (PHQ-2) in identifying major depression in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc 55: 596-602.

- Zuithoff NP, Vergouwe Y, King M, Nazareth I, van Wezep MJ, et al. (2010) The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for detection of major depressive disorder in primary care: consequences of current thresholds in a crosssectional study. BMC Fam Pract 11: 98.

- (CMO) MMCCMO (2014) CMO Data analysis and reporting.

- http://www.census.gov/

- Berkman CS, Guarnaccia PJ, Diaz N, Badger LW, Kennedy GJ (2005) Chapter 4 Concepts of mental health and mental illness in older hispanics. J Immigrant & Refugee Services 3: 59-85.

- Cooper LA, Gonzales JJ, Gallo JJ, Rost KM, Meredith LS, et al. (2003) The acceptability of treatment for depression among African-American, Hispanic, and white primary care patients. Medical care 41: 479-489.

- Medicare MPAC (2011) Medicare payment advisory committee medicare and the health care delivery system.

- Valcour VG, Masaki KH, Curb JD, Blanchette PL (2000) The detection of dementia in the primary care setting. Arch Intern Med 160: 2964-2968.

- Chang TE, Jing Y, Yeung AS, Brenneman SK, Kalsekar I, et al. (2012) Effect of communicating depression severity on physician prescribing patterns: findings from the Clinical Outcomes in MEasurement-based Treatment (COMET) trial. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 34: 105-112.

- Monsen KA, Swanberg HL, Oancea SC, Westra BL (2012) Exploring the value of clinical data standards to predict hospitalization of home care patients. Appl Clin Inform 3: 419-436.

Relevant Topics

- Addiction

- Adolescence

- Children Care

- Communicable Diseases

- Community Occupational Medicine

- Disorders and Treatments

- Education

- Infections

- Mental Health Education

- Mortality Rate

- Nutrition Education

- Occupational Therapy Education

- Population Health

- Prevalence

- Sexual Violence

- Social & Preventive Medicine

- Women's Healthcare

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 17438

- [From(publication date):

October-2016 - Aug 20, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 16559

- PDF downloads : 879