Case Report Open Access

Esthetic and Functional Rehabilitation of Molar Incisor Hypomineralisation: Report of Two Cases

Nagaveni N.B*, Shashikant Katkade, Shilpa Kothari and Poornima P

Department of Pedodontics and Preventive dentistry College of Dental Sciences, Davangere, India

- *Corresponding Author:

- Nagaveni N.B

Department of Pedodontics and Preventive dentistry

College of Dental Sciences, Davangere, India

Tel: 08105482841

E-mail: nagavenianurag@gmail.com

Received Date: April 05, 2014; Accepted Date: April 20, 2014; Published Date: April 26, 2014

Citation: Nagveni NB, Katkade S, Kothari S, Poornima P (2014) Esthetic and Functional Rehabilitation of Molar Incisor Hypomineralisation: Report of Two Cases. J Oral Hyg Health 2:130. doi: 10.4172/2332-0702.1000130

Copyright: © 2014 Nagveni NB, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Oral Hygiene & Health

Abstract

Molar incisor hypomineralization (MIH) is a relatively common condition that varies in clinical severity, localized to permanent incisors and first permanentmolars. There is no specific etiologic factor involved and remains unclear till date. Late or improper diagnosis can result in mismanagement of the condition and results in early loss of especially first permanent molars. A treatment protocol has been put forward for early identification; grading and specific treatment optionsavailable for better management of this elusive condition.This article provides diagnostic information for identification and specific protocol management of molar-incisor hypomineralisation.

Keywords

Hypomineralization; Hypoplastic; Cheesy molar

Clinical Relevance

Failure of early diagnosis and prompt treatment in cases of Molar- Incisor Hypomineralization leads to continuous enamel breakdown, increased pulpal inflammationand failure of local anesthesia complicating the further treatment modalities.

Introduction

Molar-Incisor-Hypomineralisation (MIH) is a qualitative defect of 1-4 first permanent molars with or without the maxillary and mandibular permanent incisors. It seems to have been recognized first in the 1970s and prevalence varies between 2.8% and 25% [1], dependent upon the study.

The term molar incisor hypomineralization (MIH) was introduced in 2001 to describe the clinical appearance of enamel hypomineralization of systemic origin affecting one or more permanent first molars (PFMs) that are associated frequently with affected incisors [2]. Earlier condition was referred as hypomineralized PFMs, idiopathic enamel hypomineralization, dysmineralized PFMs, non-fluoride hypomineralization and cheese molars and is attributed to disrupted ameloblastic function during the transitional and maturational stages of amelogenesis [3].

MIH’s clinical management is challenging due to: 1) the sensitivity and rapid development of dental caries in affected PFMs; 2) the limited cooperation of a young child; 3) difficulty in achieving anesthesia; and 4) the repeated marginal breakdown of restorations.

Examination for MIH should be undertaken on clean wet teeth and that the age of 8-years was optimum, as at this age all permanent first molars and most of the incisors will have erupted [4]. In addition, if it is believed that MIH is a progressive condition, then the permanent first molar teeth will be in relatively good condition without excessive post eruptive breakdown and treatment can provide at an earlier age.

Case 1

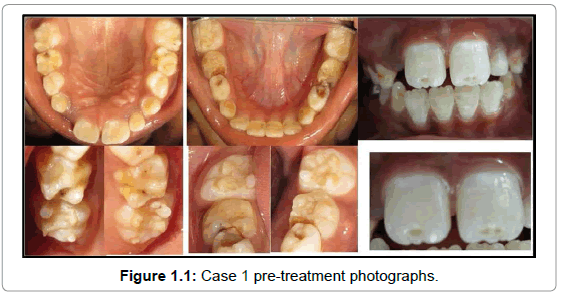

A 9-year-old boy reported to the out patient Department of Pedodontics with chief complaint of pain in lower left back teeth region of jaw. Intra oralexamination showed-deep dentinal caries with mandibular primary left second molar associated with gingival swelling and draining sinus (Figure 1.1), moderate dentinal caries with mandibular primary right first and second molars and left first molar. Clinical and radiographic examination revealed dentoalveolar abscess with mandibular primary left second molar. Presence of localized hypoplastic and hypomineralised enamel of permanent maxillary central incisors andfirst permanent molars (PFM) with no specific identifiable etiology confirmed our diagnosis as MIH (Figure 1.1). Prenatal and post natal history revealed no relevant information.

Pulp therapy was done for mandibular primary left second molar, restoration of affected incisors was done by etch-bleach-seal technique, suggested by Wright, yellow-brown defects of the lesions are etched with 37% phosphoric acid for 60 s, bleached with 5% sodium hypochlorite for 5-10 min, re-etched and covered with a composite restoration. Preformed stainless steel crown as an interim restoration for all permanent first molars was placed to prevent further tooth loss, control sensitivity and establish correct interproximal and proper occlusal contacts (Figure 1.2). Tooth preparation was done under local anesthesia to overcome the sensitivity.

Case 2

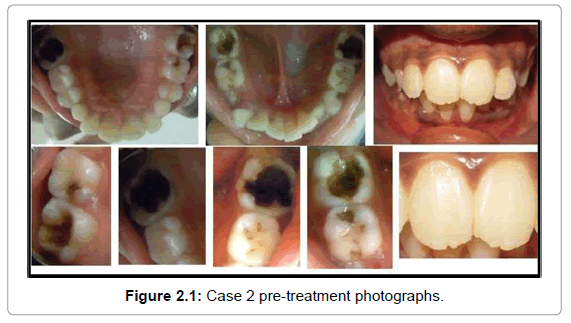

An 11-year-old girl reported to the out patient Department of Pedodontics with chief complaint of pain in lower left back teeth region of jaw since one month. Intra oral examination showed- moderate dentinal caries with mandibular primary right second molar and arrested caries with mandibular primary left first molar. Presence of deep dentinal caries of PFM secondary to hypomineralisation and hypoplasia as well as localized hypoplastic and hypomineralised enamel of permanent maxillary central incisors was also found. Radiographic examination revealed dentinal radiolucency very close to pulp of all PFM. This condition which had no specific identifiable etiology confirmed our diagnosis as MIH (Figure 2.1). Prenatal and post natal history revealed no relevant information.

Indirect pulp capping of all PFM was carried out followed by preformed stainless steel crown as an interim restoration for all permanent first molars to prevent further tooth loss, control sensitivity and establish correct interproximal and proper occlusal contacts. Affected incisors were restored as suggested by Wright using composite restoration (Figure 2.2).

Discussion

There are wide range of restorative options available to the dental clinician treating the patients with MIH: GIC, Resin Modified Glass Ionomer Cements (RMGIC), Polyacid modified composite resins (PMCR), Composite resins, amalgam and full coronal coverage restoration that includes Preformed metal crowns (PMC) or stainless steel crown (SSC).

Amalgam is a non-adhesive material and its use in these atypically shaped cavities is not indicated; the inability to protect the remaining structures usually results in further enamel breakdown [5]. Restorations with GIC, RMGIC and PMCR are not recommended in the stress bearing areas and they can only be used as intermediate approach until a definite restoration is placed [5]. GIC has been additionally proposed as an intermediate layer restoring the dentinal contours, prior to composite placement, in cases where the cavity involves large areas of dentine [6]. The only material that appears to be usable for one or more surfaces restorations in MIH molars is Composite resin. Preformed metal crowns are still recommended as a treatment option for MIH posterior teeth [5]. They prevent further tooth loss, control sensitivity, establish correct interproximal and proper occlusal contacts, are not costly and require little time to prepare and insert [7].

Based on recent research on MIH, it has been shown that 71.6% of affected children may have incisors as well as FPM involved [8]. As a result the children with MIH face serious aesthetic and psychological problems that need to be treated as early as possible. Unfortunately the literature lacks evidence-based results for the management of such defects for the anterior teeth [7]. An interesting approach, called etchbleach- seal technique, as suggested by Wright in 2002 can be employed. Some other authors have suggested the use of opaque resins and direct Composite resin veneering. Opaque resins as intermediate layer should always be considered in order to mask the reflection of the deep discolored lesions [9].

Yellow or brownish-yellow defects are of full thickness whilst those that are creamy-yellow or whitish-creamy are less porous and variable in depth [10]. As a result the former defects may occasionally respond to bleaching with carbamide peroxide [9] and the latter to microabrasion with 18% hydrochloric acid or 37.5% phosphoric acid and abrasive paste [11]. More pronounced enamel defects might be dealt with by combining the two methods [12].

Conclusions

In children, early identification and management of this condition helps in preventing first permanent molar morbidity and mortality, as enamel in this condition deteriorates quickly, making the tooth extremely sensitive and difficult to manage. Hence early identification and appropriate treatment delivery remains crucial in its management. Prospective studies in order to help clarify the etiology are required and further research is needed into restorative options. Further ultrastructural and biochemical studiescould point the way towards better management possibilities and help in the issue of etiology.

References

- Willmott NS, Bryan RA, Duggal MS (2008) Molar-incisor-hypomineralisation: a literature review. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 9: 172-179.

- Weerheijm KL, Jälevik B, Alaluusua S (2001) Molar-incisor hypomineralisation. Caries Res 35: 390-391.

- Fearne J, Anderson P, Davis GR (2004) 3D X-ray microscopic study of the extent of variations in enamel density in first permanent molars with idiopathic enamel hypomineralisation. Br Dent J 196: 634-638.

- Weerheijm KL (2003) Molar incisor hypomineralisation (MIH). Eur J Paediatr Dent 4: 114-120.

- William V, Messer LB, Burrow MF (2006) Molar incisor hypomineralization: review and recommendations for clinical management. Pediatr Dent 28: 224-232.

- Mathu-Muju K, Wright JT (2006) Diagnosis and treatment of molar incisor hypomineralization. CompendContinEduc Dent 27: 604-610.

- Lygidakis NA (2010) Treatment modalities in children with teeth affected by molar-incisor enamel hypomineralisation (MIH): A systematic review. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 11: 65-74.

- Chawla N, Messer LB, Silva M (2008) Clinical studies on molar-incisor-hypomineralisation part 1: distribution and putative associations. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 9: 180-190.

- Fayle SA (2003) Molar incisor hypomineralisation: restorative management. Eur J Paediatr Dent 4: 121-126.

- Jalevik B, Noren JG (2000) Enamel hypomineralisation of permanent first molars: a morphological study and survey of possible aetiological factors. Int J Paediatr Dent 10: 278-289.

- Wray A, Welbury R (2001) UK National Clinical Guidelines in Paediatric Dentistry: Treatment of intrinsic discoloration in permanent anterior teeth in children and adolescents. Int J Paediatr Dent 11: 309-315.

- Sundfeld RH, Croll TP, Briso AL, de Alexandre RS, SundfeldNeto D (2007) Considerations about enamel microabrasion after 18 years. Am J Dent 20: 67-72.

Relevant Topics

- Advanced Bleeding Gums

- Advanced Receeding Gums

- Bleeding Gums

- Children’s Oral Health

- Coronal Fracture

- Dental Anestheia and Sedation

- Dental Plaque

- Dental Radiology

- Dentistry and Diabetes

- Fluoride Treatments

- Gum Cancer

- Gum Infection

- Occlusal Splint

- Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology

- Oral Hygiene

- Oral Hygiene Blogs

- Oral Hygiene Case Reports

- Oral Hygiene Practice

- Oral Leukoplakia

- Oral Microbiome

- Oral Rehydration

- Oral Surgery Special Issue

- Orthodontistry

- Periodontal Disease Management

- Periodontistry

- Root Canal Treatment

- Tele-Dentistry

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 18654

- [From(publication date):

May-2014 - Aug 31, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 13845

- PDF downloads : 4809