Picture Books and Reading Aloud to Support Children after a Natural Disaster: An Exploratory Study

DOI: 10.4172/1522-4821.1000414

Abstract

Objective: Picture books have been used after disasters to support children’s recovery, without empirical validation. This study explored the long-term effects of a modified Reach Out and Read (ROR) intervention after a typhoon in the Philippines.

Methods: Two months following Typhoon Haiyan, doctors trained parents and children in reading aloud and distributed picture books. Thirteen months later, participants described their reactions to the typhoon and the intervention, and answered the CRIES-8 trauma symptom questionnaire.

Results: Subjects were 113 working-class parents and their children, 6 months to 11 years of age. At follow-up, 47% mentioned the books in response to an open-ended question about interventions that had helped them. Qualitative responses indicated the books were seen in equal measure as supporting education and helping children to feel happy again; nonetheless 21% of the children scored in the clinical range on the CRIES-8. Higher CRIES-8 scores were associated with severity of initial stress reactions (but not extent of injury, death, and loss), and with more recent use of the intervention books.

Conclusion: More than a year following a natural disaster, survivors recalled being helped by a modest intervention providing picture books and guidance about reading aloud; many continued using the books. Recent book use was associated with higher post-traumatic symptoms. Book-based interventions may help to mitigate the effects of natural disasters.

Keywords: Reading aloud, Books, PTSD, Recovery, Intervention, Philippines, Reach Out and Read

Introduction

Picture books serve many purposes in the lives of children. They can play important roles in daily routines; reading aloud by parents offers children entertainment and interaction, while exposure to books promotes language development, print awareness, and familiarity with story structures and conventions. Linguistically rich interactions play a role in literacy acquisition and later academic success, and also nurture children’s emotional development. Interventions that enhance responsive reading aloud have been shown to reduce parenting stress and depression, as well as the use of harsh discipline and child behavior problems (Berkule et al., 2014; Cates et al., 2016; Mendelsohn et al., 2018, 2007; Weisleder et al., 2016). By strengthening parent-child communication and emotional connection, picture books and the stories they convey may bolster children’s resilience in the face of stressors, mild and severe (Murray, 2018; Shonkoff, Garner, Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care, & Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 2012). In addition to supporting comforting parent-child interactions, picture books are symbolic links to education and school. As such, they serve as reminders of the everyday activities that provide structure in children’s lives, suggesting an optimistic future of safety and accomplishment, and may assist in children’s educational recovery after disasters (Olness, Sinha, Herran, Cheren, & Pairojkul, 2005; Peek & Richardson, 2010).

For these reasons, it is reasonable to expect that picture books might be helpful to children exposed to the extreme stresses that accompany war and natural disasters. Picture books have been included in UNICEF’s “Return to Happiness” program, first employed in 1992 in Mozambique, and later throughout Central America (“Progress Evaluation of UNICEF‟s Education in Emergencies and Post-Crisis Transition Programme: Colombia Case Study,” 2010; UNICEF, 2009). One of the books used in the program features a traumatized little monkey who is too agitated to sleep. His mother appears uninterested in his distress until the moon (in the role of therapist) teaches her how to sing to him, reestablishing their connection and his security. The book thus provides both a comforting story and implicit instructions to parents who themselves have experienced trauma. Books were distributed following the tsunami in Thailand in 2004; in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in 2005; and following the earthquake in Haiti in 2010. However, the effectiveness of picture books paired with guidance about reading aloud has not been evaluated as an adjunct to other interventions intended to promote psychosocial recovery after exposure to natural disasters.

On November 8, 2013, Typhoon Haiyan (aka Yolanda) hit the Philippines. One of the strongest storms ever recorded in that country, it was also the deadliest, claiming more than 6,000 lives. In the aftermath of the typhoon, the leadership of a national association of pediatricians decided to contribute to the efforts of other governmental and non-government institutions that were providing humanitarian and disaster relief. Working together with officials of the federal and local Departments of Health, Education and Social Welfare, the pediatricians designed a brief intervention to teach parents to use reading aloud as a way of supporting children’s emotional recovery. Pediatricians and teachers worked with groups of children and families, explaining the value of shared reading and modeling effective reading aloud techniques. Sessions typically lasted a little over an hour. Picture books were provided to families to take home. This intervention was modified from Reach Out and Read (ROR), a widely-implemented program.

It was hoped that helping families develop reading aloud routines might prove comforting to children who were struggling with fears and loss in the aftermath of the typhoon. Preliminary observations made during the initial sessions suggested that this might be the case. During the reading sessions, parents and children were responsive. One pediatrician recalled, “We observed in the eager and happy faces of the children who received the books and clasped these to their chest, in the grateful smile of the parents, and the deep appreciation of the teachers that the books had brought some pleasure and meaning to their lives during this period of transition.”

Aim

The purpose of the present study was to explore the longerterm effects of the intervention, using a combination of qualitative and quantitative data, collected 13 months following the initial intervention. We hypothesized that symptoms of PTSD at followup would be related both to the severity of the losses endured by the children and to their recalled emotional responses to those losses. Although we did not expect our very modest intervention to prevent the development of PTSD, we thought that story books and developmentally appropriate guidance introduced relatively early in the post-disaster recovery period might partially ameliorate the trauma-related symptoms of children who had lived through the typhoon. We hoped that qualitative reports from the parents and children would illuminate ways in which the modified ROR intervention had affected children’s recovery.

Methods

The study used a retrospective, mixed-methods approach to assess trauma exposure, trauma-related symptoms, and parents’ and children’s subjective responses to the typhoon and to the modified ROR intervention. The intervention and data collection were planned in close coordination with local government officials and with the Philippines Department of Health, the Department of Education, and the Department of Social Welfare and Development. The Chair of the Philippines Research Ethics Board advised that review by his office was not necessary, in light of the endorsement by the relevant agencies, and his judgment that the intervention was timely, safe and urgently needed. The principles that comprise the Declaration of Helsinki informed the design and execution of this study, in particular autonomy, beneficence, and respect for vulnerable populations.

Baseline Sample Recruitment and Intervention: The intervention took place in January, 2014, approximately 2 months after the typhoon. Pediatricians traveled to three of the most severely affected municipalities. Under direction from the relevant government agencies, local teachers and social workers identified families who were at greatest need of assistance, and personally invited them to participate in the intervention. Participating families were grouped according to the age of children: infant to preschool (6 months through 3 years), early school aged (4 to 7) and older school age (8 to 11). Within each group, leaders described the benefits of reading aloud as a way to calm and connect with children, and an ageappropriate storybook was read aloud, with the parent(s) present. Older children were also invited to read aloud to the rest of the children in the group. Each child was invited to take home a new copy of one of the books that had been featured in the training session. The books were chosen to include themes of recovery or optimism, including a book in which a child decides to take care of the ocean, to keep it beautiful and healthy, and a book on taking care of plants in the garden. Volunteers collected contact information from the families.

Follow-Up Data Collection: Follow-up interviews were conducted in February, 2015, approximately 13 months after the intervention. Using the sign-up list from the trainings, the same teachers and social workers who had recruited families to the intervention contacted families to participate in the follow-up. Parents who participated were given token financial compensation (approximately $2) and another picture book.

Written informed consent was not obtained, but all participants were told that the interview was entirely voluntary and optional, and that they were entitled to refuse or to stop at any time; therefore, the participants’ willingness to proceed with the interview was taken to signify assent. The interviews were administered verbally, in either English or local dialect depending on the participants’ preference, by pediatricians who had been involved in the original intervention.

For children less than 6 years of age, the respondents were the parents. Children 6 and older were interviewed directly, with help from their parents as needed. The interview included basic demographics, descriptions of the nature of the losses incurred as a result of the typhoon, and descriptions of the child’s experience in the immediate aftermath, including symptoms of stress. Stress symptoms were elicited through multiple yes/no questions, for example, respondents were asked if the child had experienced any of 8 reactions including, e.g., nightmares, loss of appetite, extreme fears, loss of concentration, and “other.” Recall of the intervention was ascertained in two ways. First, respondents were given an openended question asking about help they received after the typhoon. The response was scored positive for “un-prompted recall” if it mentioned having gotten a book at the intervention session. Second, respondents who had not demonstrated un-prompted recall were asked directly if they recalled having gone to a session 2 months after the typhoon in which doctors talked about reading aloud and gave out books. Affirmative responses to this closed-ended question were scored positive for “prompted recall”. Respondents were also asked to describe how the book-based intervention had been useful to them. The interview concluded with the 8 questions comprising the CRIES-8, a widely-used measure of PTSD-related symptoms (Deeba, Rapee, & Prvan, 2014).

Data analysis: In order to gauge the severity of losses experienced, an index of “injury severity” was created using the following formula: 2 points for injury to the child, plus 1 point for injury to a parent(s), plus ½ point for injury to a sibling or other relative. A similar formula was used to quantify deaths: 2 points for death of a parent (no child lost both parents), plus 1 point for death of a sibling(s), plus ½ point for death of other relative(s) or friend(s). As a measure of the intensity of the child’s immediate response to the trauma, each stress symptom was given a value of 1, and the symptom total was calculated. An index reflecting how recently the book had been last used by the parent or child was created using the following formula: 4 points for last use in the previous week, 3 points for last use in the past month, 2 points for last use in the past 6 months, and 1 point for use within the past year. Responses to open-ended questions about how the books had been helpful were recorded by the interviewer, and later grouped according to common themes (Flick, 2019).

CRIES-8 scores were treated both as a continuous variable, and as a dichotomous variable using a cutoff score of 17 following Perrin, et al. (Perrin, Meiser-Stedman, & Smith, 2005). Data cleaning resulted in 18 CRIES-8 scores being discarded because of coding irregularities. Analyses included descriptive statistics, ANOVA and multiple linear regressions. All analyses were done using SPSS version 25.

Results

Approximately 500 children participated in the modified ROR sessions, 256 of whom provided contact information. At followup 13 months later, 113 interviews were completed (57% of the original 256). Table 1 presents demographic data.

| Interviewed Group n=113* n, (%) | |

| Child Age (years) <6 yrs ≥6 yrs. |

mean 7.1 ± sd 3.6 8 (24.2) 25 (75.8) |

| Child sex Female Male |

58 (51.3) 49 (43.4) |

| Municipality Town A Town B Town C |

49 (43.4) 23 (20.4) 41 (36.3) |

Table 1: Demographic data

For the most part, the families were working class. Of those parents who provided an education level, roughly 50% endorsed high school, 30% elementary school, and 20% college. Some of the more common job descriptions included housewife, pedicab driver, vendor, and fisherman; among those with more education were electricians, a fisherman, a government employee, and a teacher. Prior to the typhoon, most of children in both intervention and comparison groups were living in their own houses (99% and 88%, respectively), and only a few reported living with relatives or in other housing.

The children suffered dire losses during the typhoon, including the loss of homes and other property, serious injuries to self and family members, and deaths of family members and friends (Table 2).

| Intervention Group n=113 n, (%) | |

| House lost | 104 (92.0) |

| Other property lost | 95 (84.1) |

| Injuries Self Parent Sibling |

8 (7.1) 27 (23.9) 15 (13.3) |

| Deaths Parent Sibling Relative/friend |

6 (5.3) 2 (1.8) 63 (55.8) |

Table 2: Losses, injuries, and deaths.

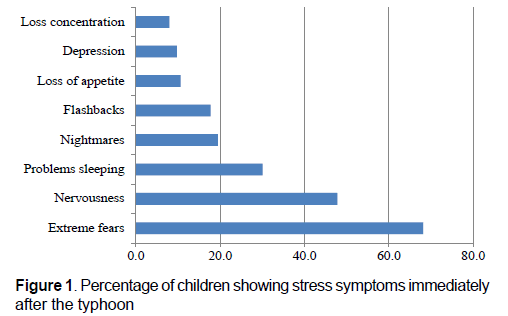

Interviewed 13 months later, they recalled experiencing many stress symptoms in the immediate aftermath of the storm (Figure 1). Families and children received a range of assistance in the aftermath of the storm, both from the government and NGO sources, including necessities such as food, housing, and cash (94% of respondents), and other goods such as school supplies, crayons, paper, or toys (31%).

Of the 113 children, 53 (47%) mentioned the modified ROR session in response to an open-ended question about help they had received in the immediate post-storm period (i.e., “unprompted recall”). In response to a direct question, another 50 (44%) recalled having taken a book. When asked, “Did the book make you/your child feels better,” 100% responded affirmatively. At follow-up 13 months later, 64 (57.5%) reported that they still possessed the book; 29 (26%) reported that they had looked at the book within the past year; 22 (20%) within the past 6 months; 14 (12%) within the past 1 month; and 36 (32%) within the past week. Of the 48 children who did not still have their book, in 25 (52 %) the book was reported to have been destroyed in a subsequent typhoon (Typhoon Ruby); in 19% the books had been destroyed by another person; in 8% they had been given away to a relative or friend; and in 21% they had been lost or stolen.

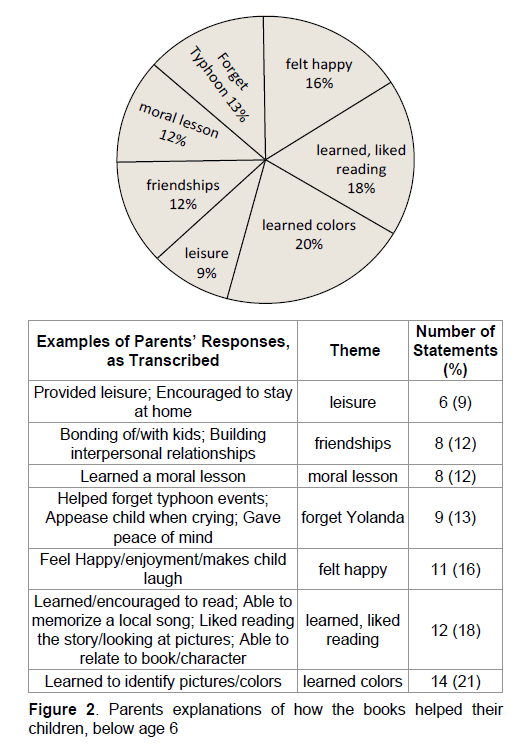

Parents and children told of various ways the books had helped them (Figure 2). Two main themes emerged from these responses: learning, and comfort/happiness. For younger children, 16% of the parents believed that reading aloud made their children happy, and 13% specifically mentioned that the stories helped their children forget the typhoon. Among the older children, 48% reported that the picture books made them feel happier or “better,” and 6% specifically mentioned that the book helped them forget the typhoon. (The percentages sum to >100% because respondents often gave multiple reasons.) Table 3 presents representative quotations from parents and children, some translated from the Filipino language.(i.e. PTSD) range. In univariate analyses, the CRIES-8 total score was associated with the total number of immediate stress symptoms (Pearson r=.429, p<.001), and with the town (ANOVA F=3.4, p<0.04); but not with our summed index of injury, death and property loss (r-.17, ns). Among the 53 subjects with un-prompted recall of the book, 30% reported CRIES-8 scores in the clinical range, compared to 13% of the 60 subjects who did not have unprompted recall. There was also an association between CRIES-8 score and our index of recent book use: the more recent the book use, the higher the CRIES-8 score (F=3.6, p<0.02). In a categorical analysis, 30% of children who were reported to have used the book within the past month reported CRIES-8 scores at or above 17 (i.e., in the clinical range) compared with 14% of 51 children who had not used the book as recently (chi-sq 3.9, p<0.05).

| It helped the child by way of forgetting some bad memories. (Mother of 5 yr old/female) |

| (The book) alleviated the children's fears. It provided them leisure. My daughter became sad when her book got wet by the recent storm. (Mother of a 5 yr old/female |

| (The book) relieved her of her trauma. (Mother of a 5 yr old/female) |

| She was happy and forgot about the loss of their house, death of her aunt and of strong winds and waves. (9 yr old/female) |

| The child feels happy about the book and his parents would read it before he goes to sleep. (9 yr old/male) |

| The book made me feel better (at ease). (15 yr old/female) |

| The child told the story of the book, how the character after the war planted again. The child loves plants so the book made her thinking to plant again. (10 yr old/female) |

| The child learned to take care of the environment, appreciate flowers and started to plant. (14 yr old/female) |

Table 3. Representative quotations from parents and children, some translated from the Filipino language

In a multiple linear regression analysis controlling for town, child sex, extent of reported losses, severity of initial stress symptoms, un-prompted recall of the book, and recent book use, only initial stress symptoms and recent book use remained significantly associated with total CRIES-8 score (beta =2.0, p<0.001; and beta =1.26, p<0.023, respectively).

Discussion

This is the first study we know that has evaluated the use of picture-books and training in reading aloud as an adjunct to other supports provided immediately following a natural disaster. The intervention was modeled after Reach Out and Read (ROR), modified for the post-disaster setting. Since 2007, ROR had been implemented as part of the Outpatient Services in several hospitals in the Philippines, and thus was familiar to the team of doctors who carried out the intervention. The central components of ROR are expert advice, modeling of developmentally appropriate reading aloud, and provision of developmentally and culturally appropriate picture books at each health supervision visit beginning in infancy. Numerous studies have documented the efficacy of this approach in promoting language development and positive reading aloud interactions within families challenged by educational and social disadvantage (R. D. Needlman, Dreyer, Klass, & Mendelsohn, 2019; R. Needlman & Silverstein, 2004; R. Needlman, Toker, Dreyer, Klass, & Mendelsohn, 2005; Zuckerman & Augustyn, 2011).

The current study adds to the existing body of evidence by demonstrating long-term outcomes of a ROR-like intervention in families traumatized by a natural disaster. In a group of children and parents who had participated in the intervention 2 months after the typhoon and who were interviewed 13 months later, nearly half recalled the intervention in response to an open-ended question about interventions that had helped them. Respondents described how the books supported learning and literacy, and contributed to pleasure, comfort, and resilience. Parents and children prized the books. Few of them had been misplaced; some had been shared with friends. Of those that were lost, in many cases the identified cause was a subsequent typhoon. Overall, just over one half of the children still had the books given to them as part of the brief intervention; many were still making use of them on a regular basis. We observed an association between recent book use and higher scores on a standardized measure of PTSD-related symptoms, even after controlling for potential confounding factors.

As a group, the children in our study were severely traumatized. Most of them lost their homes to the storm, lost family members, or suffered serious injuries. From the vantage point of a year later, they reported having experienced multiple symptoms of stress, such as sleeplessness and extreme fears. One year later, more than one fifth of the children were experiencing symptoms above the usual cutoff for PTSD. In partial support of our hypotheses, the number of PTSD symptoms at follow up was associated with the extent of stress symptoms in the immediate aftermath, but not with the extent of initial losses.

Other than initial stress responses, the only factor found associated with PTSD symptoms was recent use of the intervention books. This association requires interpretation, because the causal arrow could point in either direction. Several items on the CRIES-8 reference unwanted memories and avoidance of reminders. If the books reminded children of the immediate post-typhoon period, it is possible that looking at the books could serve to exacerbate these symptoms, as though the book use were a manifestation of compulsive repetition. This interpretation, while possible, seems unlikely. In their qualitative responses, children identified the books as sources of educational stimulation, comfort or both; nearly all endorsed the statement that the books were “helpful.” Therefore, a more plausible explanation is that many of the children who continued to experience traumatic symptoms continued to make use of the books as a source of comfort. They were more likely to have used them recently, because they were in greater need of comfort. Our data do not allow us to unpack which aspect of the books – their association with learning and school, the optimistic stories they contained, or the connection with loving parental interactions – may have been instrumental in conveying comfort. Moreover, we cannot exclude the possibility that the observed association between recent use and trauma symptoms was an artifact of the interview process: perhaps remembering the book intervention cast the respondents’ minds back to a stressful time, leading them to report their current symptoms at a higher level.

This exploratory study has several other limitations. Lacking a control group, it cannot establish causality. The interviews were necessarily brief, and did not permit detailed descriptions of the children’s experiences nor of the traumas experienced by their parents and other family members, nor of ongoing stresses (e.g. domestic violence or poverty) which play an important role in the persistence of PTSD symptoms (Fernando, Miller, & Berger, 2010); nor of any other therapeutic inputs which might have aided the children’s recovery. Verbal responses were transcribed by the interviewers rather than recorded electronically, and therefore could have incorporated the interviewers’ biases. Retrospective reports of losses and symptoms in the immediate aftermath were subject to recall bias; children experiencing higher levels of post-traumatic symptoms a year out might have been biased toward amplifying their recollections of immediate trauma. Social desirability may have colored some of the responses as well.

Nonetheless, as an initial exploration of a potentially useful intervention, our study contributes new information to the study of psychosocial supports offered to children exposed to natural disasters (Chemtob, Nakashima, & Hamada, 2002; Forman- Hoffman et al., 2013; Peek, 2008; Pfefferbaum, Newman, & Nelson, 2014a). In recent years, Reach Out and Read and related interventions have begun to spread to under-resourced areas of the globe that are disproportionately vulnerable to natural disasters (Srivastava et al., 2015). As a result, going forward there are likely to be more opportunities to incorporate books and guidance about reading aloud into the disaster response through the efforts of local professionals, as in the current study. Whether or not it makes sense to offer books and guidance about reading aloud following disasters depends on our confidence that such interventions are helpful. This question has not heretofore been examined empirically. For example, a recent special issue of Child Development devoted entirely to children’s psychosocial responses to natural and manmade disasters did not address the potential value of reading aloud (Ager, Stark, Akesson, & Boothby, 2010); nor did a systematic review of psychosocial interventions for children exposed to disasters (Pfefferbaum, Newman, & Nelson, 2014b). Therefore, the present study has merit in beginning the discussion, even though the data are not definitive. Given the limitations of using a brief measure of trauma symptoms as the main quantitative outcome, the qualitative data become that much more important. Our respondents told us that the picture books brought happiness and relief and promoted learning. In some cases, they led the children to think more optimistically about the world around them and their own futures.

Conclusion

Certainly, it makes sense to empower parents to provide comfort and hope. The growing list of natural and human-created disasters, in which children are particularly vulnerable, is paralleled by an expanding body of knowledge about the immediate and longterm needs of the children and the interventions which support their recovery. Interventions that deliver picture books paired with guidance about reading aloud may prove to be a scalable, wellaccepted, and enduring adjunct to existing approaches.

Conflicts of Interest and Sources of Funding

The work described in this article was funded by the Philippine Ambulatory Pediatric Association (PAPA), a non-profit organization. The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgements

PAPA pediatricians Drs Rosalia Buzon, Cecil Gan, Wenslyn Salvador, Angelie Tomas, Ofelia Alcantara, and Florianne Valdes. Thanks to Adam Perzinsky, PhD, for his statistical expertise and consultation.

References

- Ager, A., Stark, L., Akesson, B., &amli; Boothby, N. (2010). Defining best liractice in care and lirotection of children in crisis-affected settings: a Dellihi study. Child Dev, 81(4): 1271-1286. Berkule, S. B., Cates, C. B., Dreyer, B. li., Huberman, H. S., Arevalo, J., Burtchen, N., et al. (2014). Reducing maternal deliressive symlitoms through liromotion of liarenting in liediatric lirimary care. Clin liediatr, 53(5): 460-469. Cates, C.B., Weisleder, A., Dreyer, B.li., Johnson, S.B., Vlahovicova, K., Ledesma, J., et al. (2016). Leveraging Healthcare to liromote Reslionsive liarenting: Imliacts of the Video Interaction liroject on liarenting Stress. J Child Fam Stud, 25(3): 827-835. Chemtob, C.M., Nakashima, J.li., &amli; Hamada, R.S. (2002). lisychosocial intervention for liostdisaster trauma symlitoms in elementary school children: a controlled community field study. Arch liediatr Adolesc Med, 156(3): 211-216. Deeba, F., Raliee, R. M., &amli; lirvan, T. (2014). lisychometric lirolierties of the Children’s Revised Imliact of Events Scale (CRIES) with Bangladeshi children and adolescents. lieerJ, 2: e536. Fernando, G.A., Miller, K.E., &amli; Berger, D.E. (2010). Growing liains: the imliact of disaster-related and daily stressors on the lisychological and lisychosocial functioning of youth in Sri Lanka. Child Dev, 81(4): 1192-1210. Flick, U. (2019). An Introduction to Qualitative Research (Sixth edition). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE liublications Ltd. Forman-Hoffman, V.L., Zolotor, A.J., McKeeman, J.L., Blanco, R., Knauer, S.R., Lloyd, S.W., et al. (2013). Comliarative effectiveness of interventions for children exliosed to non-relational traumatic events. liediatrics, 131(3): 526-539. Mendelsohn, A.L., Cates, C.B., Weisleder, A., Berkule Johnson, S., Seery, A.M., Canfield, C.F., et al. (2018). Reading Aloud, lilay, and Social-Emotional Develoliment. liediatrics, 141(5). Mendelsohn, A.L., Valdez, li.T., Flynn, V., Foley, G.M., Berkule, S.B., Tomolioulos, S., et al. (2007). Use of videotalied interactions during liediatric well-child care: imliact at 33 months on liarenting and on child develoliment. J Dev Behav liediatr, 28(3): 206-212. Murray, J. S. (2018). Toxic stress and child refugees. J Sliec liediatr Nurs, 23(1): e12200. Needlman, R.D., Dreyer, B.li., Klass, li., &amli; Mendelsohn, A L. (2019). Attendance at Well-Child Visits After Reach Out and Read. Clin liediatr, 9922818822975. Needlman, R., &amli; Silverstein, M. (2004). liediatric interventions to suliliort reading aloud: how good is the evidence? J Dev Behav liediatr, 25(5): 352-363. Needlman, R., Toker, K.H., Dreyer, B li., Klass, li., &amli; Mendelsohn, A. L. (2005). Effectiveness of a lirimary care intervention to suliliort reading aloud: a multicenter evaluation. Ambulatory liediatrics: J Ambul liediatr Assoc, 5(4): 209-215. Olness, K., Sinha, M., Herran, M., Cheren, M., &amli; liairojkul, S. (2005). Training of Health Care lirofessionals on the Sliecial Needs of Children in the Management of Disasters: Exlierience in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Ambul liediatr, 5(4): 244-248. lieek, L. (2008). Children and Disasters: Understanding Vulnerability, Develoliing Caliacities, and liromoting Resilience. An Introduction. Child Youth Environ, 18(1): 1-29. lieek, L., &amli; Richardson, K. (2010). In their own words: dislilaced children’s educational recovery needs after Hurricane Katrina. Disaster Med liublic Health lireli, 4 Sulilil 1: S63-70. lierrin, S., Meiser-Stedman, R.., &amli; Smith, li. (2005). The Children’s Revised Imliact of Event Scale (CRIES): Validity as a Screening Instrument for liTSD. Behav Cogn lisychother, 33(4): 487-498. lifefferbaum, B., Newman, E., &amli; Nelson, S.D. (2014a). Mental health interventions for children exliosed to disasters and terrorism. J Child Adolesc lisycholiharmacol, 24(1): 24-31. lirogress Evaluation of UNICEF‟s Education in Emergencies and liost-Crisis Transition lirogramme: Colombia Case Study. (2010). United Nations Children‘s Fund, New York. Shonkoff, J. li., Garner, A. S., Committee on lisychosocial Asliects of Child and Family Health, Committee on Early Childhood, Adolition, and Deliendent Care, &amli; Section on Develolimental and Behavioral liediatrics. (2012). the lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. liediatrics, 129(1): e232-246. Srivastava, G., Bhatnagar, S., Khan, H., Thakur, S., Khan, K.A., &amli; lirabhakar, B.T. (2015). Imliact of a clinic based literacy intervention Reach Out and Read (ROR) modelled lirogram on lireschool children in India. Int J Contemli liediatrics, 2(4): 345-348. UNICEF (2009). Colombia: Evaluation of the ‘Return to Haliliiness’ methodology as a strategy for lisychosocial recovery and as a comlionent of the strategy for lireventing the recruitment of children and adolescents by illegal armed groulis. Retrieved from httlis://www.unicef.org/evaldatabase/index_67861.html Weisleder, A., Cates, C.B., Dreyer, B.li., Berkule J.S., Huberman, H.S., Seery, A.M., et al. (2016). liromotion of liositive liarenting and lirevention of Socioemotional Disliarities. liediatrics, 137(2): 1-9. Zuckerman, B., &amli; Augustyn, M. (2011). Books and Reading: Evidence-Based Standard of Care Whose Time Has Come. Acad liediatr, 11(1): 11-17.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 4651

- [From(publication date): 0-2019 - Dec 20, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 3641

- PDF downloads: 1010