Research Article Open Access

Profiling Psychiatric Inpatient Suicide Attempts in Japan

Katsumi Ikeshita1, Shigero Shimoda1, Kazunobu Norimoto2, Keisuke Arita1, Takuya Shimamoto4, Kiyoshi Murata3, Manabu Makinodan1*, Toshifumi Kishimoto1

1Department of Psychiatry, Nara Medical University, Japan

2Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine, Nara Medical University, Japan

3Preventive Health Division, Nara Prefecture Office, Japan

4Osaka Psychiatric Medical Center, Japan

Visit for more related articles at International Journal of Emergency Mental Health and Human Resilience

Abstract

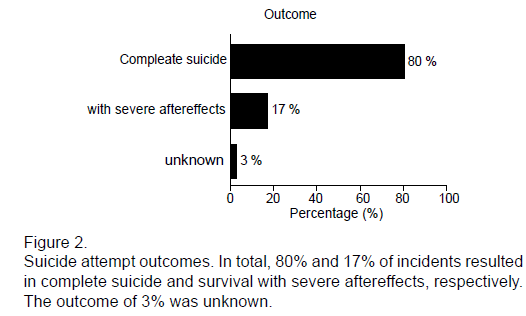

Suicide is an adverse event that can occur even when patient are hospitalized in psychiatric facilities. This study delineates the demographic characteristics of suicide attempts in mental hospitals and psychiatric wards of general hospitals in Japan, a country where the suicide rate is remarkably high. Analyses of incident reports on serious suicide attempts in psychiatric inpatients were performed using prefectural incident records between April 1, 2001, and December31, 2012. Suicide reports were included for 35 incidents that occurred over 11years, and demonstrated that 83% of patients (n=29) committed suicide and 17% (n=6) survived their attempt with serious aftereffects, such as cognitive impairment or persistent vegetative state. The male/female ratio of inpatient suicide was 1.5:1. The mean age of the attempters was 50.5 years (SD = 18.2). The most common psychiatric diagnoses for those with suicide incident reports were schizophrenia spectrum disorders (51.4%) and affective disorders (40%). Hanging (60%) was the most common method of suicide attempt, followed by jumping in front of moving objects (14.3%) and jumping from height (11.4%). Fifty-four percent of suicides (n=19) occurred within hospital sites and the remainder (46%; n=16) occurred outside hospital sites (e.g., on medical leave or elopement) while they were still inpatients.

Keywords

Inpatient, suicide, Psychiatry, Japan

Introduction

Suicide is a worldwide public health issue. According to a World Health Organization (WHO) report, one million people per year commit suicide throughout the world (WHO, 2013). It is noteworthy that in Japan, more than 30,000 suicide incidents have occurred per year for 14 consecutive years since 1998 (Cabinet Office, Government of Japan, 2013). Although the number of suicides has slightly decreased in the last two years, the suicide rate is still remarkably high at approximately 22 per 100,000 persons (WHO, 2013). In the Nara prefecture of Japan, approximately 250 people (roughly 18 per 100,000 persons) commit suicide every year (National Police Agency, 2013). Compared with other countries the rate of suicide in Japan is higher than the rate in the United States (11 per 100,000 in 2002) (Mann et al., 2005) and the average world rate (14.5 per 100,000) (Hawton & Heeringen, 2009).

There is a strong association between suicide and psychiatric disorders, and studies show that more than 90% of all completed suicides fulfill the criteria for at least one psychiatric diagnosis (Conwell et al., 1996; Foster, Gillespie & McCelland, 1997; Isometsa et al., 1995). Psychiatric inpatients are known to be at high risk for suicide (Appleby, 1992) with a prevalence rate of 13.7 per 10,000 admissions (0.137%) (Powell, Geddes, Deeks, et al., 2000). While suicide is the second most common adverse event in hospitals, following wrong-site surgery (The Joint Commission, 2013), there are few studies which have examined hospital suicide incidents in detail. In this report, we define the demographic characteristics of suicide attempts that occur in inpatient psychiatric settings in Nara Japan.

Materials and Methods

Participants

The study participants were inpatients who attempted suicide during hospitalization between April 1, 2001 and December 31, 2012. We obtained personal data from incident reports provided by the Nara Preventive Health Division of the Nara Prefecture Office. The incident reports were submitted from nine mental hospitals and one psychiatric ward of a general hospital in Nara, for a total of 2,700 psychiatric inpatient beds.

Procedures

Incident reports were submitted to the prefecture office from mental health hospitals when a serious incident occurred. We retrospectively investigated and analyzed the data regarding serious suicide attempts in psychiatric inpatients using these reports. We collected clinical data and demographic characteristics: age, sex, diagnosis, method of suicide attempt, time and location of incident, and outcome. Psychiatric diagnoses from medical records were based on the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10).

Results

Thirty-five incidents of attempted suicide were reported over the eleven-year period. The inpatient and suicide attempt characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The number of suicide attempts was higher in males (60%; n=21) than females (40%; n=14), and the mean age of the attempters was 50.5years (SD=18.2) (males, 51.6 years, SD=17.8; females, 48.8 years, SD=19.3). The age ranges in which the highest number of suicide attempts took place was 40–49 and 60–69 years. The most common psychiatric diagnoses wereschizophrenia spectrum disorders (51.4%; n=18) and affective disorders (40%; n=14). With regard to when suicides took place, 31% (n=11) occurred during the night (20:00–8:00) and 66% (n=23) occurred during the day (8:00–20:00). Fifty-eight percent (n=11) and 42% (n=8) of the incidents which took place within hospital sites occurred during the day (8:00–20:00) and night (20:00–8:00), respectively. There were also 16 suicide attempts that occurred outside hospital sites.

| ��? | Malen=21 (%) | Femalen=14 (%) | Alln=35 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (S.D.) | 51.6 (17.8) | 48.8 (19.3) | 50.5 (18.2) |

| Age | |||

| 10-19 | 0 | 1 | 1 (3) |

| 20-29 | 3 | 1 | 4 (11.4) |

| 30-39 | 3 | 2 | 5 (14.3) |

| 40-49 | 3 | 4 | 7 (20) |

| 50-59 | 3 | 3 | 6 (17.1) |

| 60-69 | 5 | 2 | 7 (20) |

| 70-79 | 3 | 0 | 3 (8.6) |

| 80-89 | 1 | 1 | 2 (5.7) |

| Diagnosis (ICD-10) | |||

| F1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| F2 | 10 | 8 | 18 |

| F3 | 9 | 5 | 14 |

| F4 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| F5 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Suicide Method | |||

| Hanging | 10 | 11 | 21 |

| Jumping in front of a moving vehicle | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| Jumping from height | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Head injury | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Cutting | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Drowning | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Gas-poisoning | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Suffocation | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Suicide Location | |||

| Within hospital site | 8 | 11 | 19 |

| Outside hospital site | 13 | 3 | 16 |

F1: Mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use

F2: Schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders

F3: Mood disorders

F4: Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders

F5: Behavioural syndromes associated with physiological disturbances and physical factors

Table 1: Characteristics of psychiatric inpatients and methods of suicide attempt

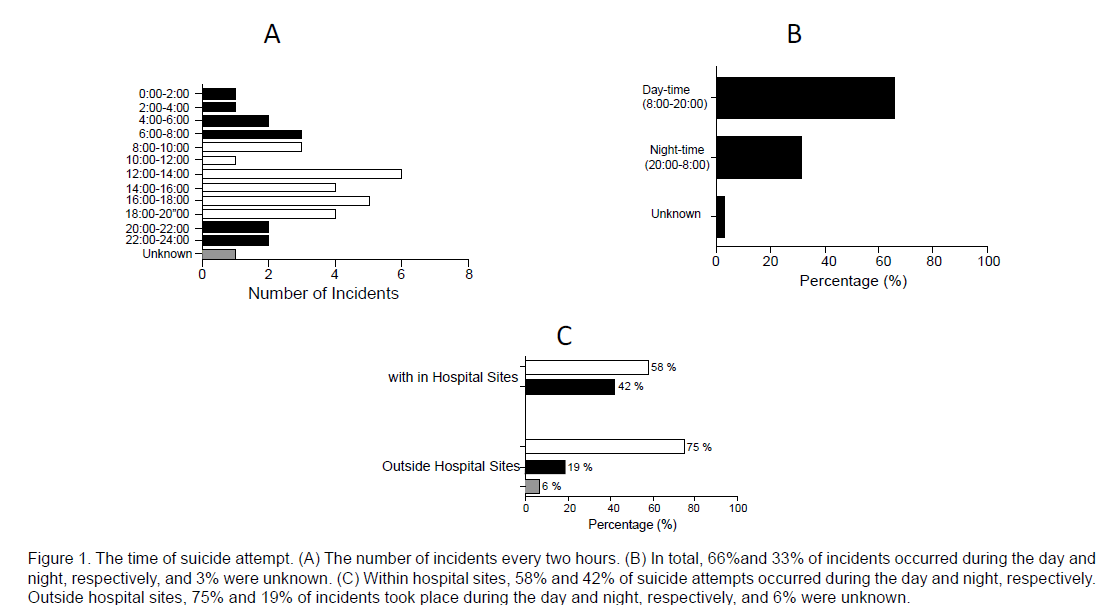

Eleven of 16 attempts occurred while patients were on a medical leave from the hospital and the other five occurred after patients eloped. Suicide attempts outside hospital sites occurred predominantly during the day (75%; n=12) versus the night (19%; n=3), with one occurring at an unknown time (Figure 1). Hanging (60%; n=21) was the most common method of suicide attempt followed by jumping in front of moving objects (14.3%; n=5), and jumping from height (11.4%; n=4) (Table 1). The relation between suicide locations and methods is shown in Table 2. Fifty-four percent (n=19) of these suicide attempts occurred within hospital sites, 79% (n=15) of which were completed by hanging. Of the 46% (n=16) of suicides that occurred outside hospital sites, 37.5% (n=6), 31.3% (n=5), and 18.8% (n=3) were completed by hanging, jumping in front of moving objects, and jumping from height, respectively. Hanging with a towel or belt on a doorknob or a bedside rail was the most common method of suicide in hospital rooms (data not shown). With regard to outcome, 80% of the incidents (n=28) resulted in completed suicide and 17% (n=6) survived with serious aftereffects such as cognitive impairment and persistent vegetative state; one case was unknown (Figure 2).

| Within hospital site n=19 (54 %) | Outside hospital site n=16 (46 %) | |

|---|---|---|

| Hanging | 15 (78.9 %) | 6 (37.5 %) |

| Jumping in front of a moving vehicle | 0 (0 %) | 5 (31.3 %) |

| Jumping from height | 1 (5.3 %) | 3 (18.8 %) |

| Head injury | 1 (5.3 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| Cutting | 1 (5.3 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| Drowning | 0 (0 %) | 1 (6.3 %) |

| Gas-poisoning | 0 (0 %) | 1 (6.3 %) |

| Suffocation | 1 (5.3 %) | 0 (0 %) |

| Bold number: percentage of total incidents��? ��? | ||

| Italic number: percentage of incidents either within hospital site or outside hospital site | ||

Table 2: Relationship between Location and Methods

Figure 1: The time of suicide attempt. (A) The number of incidents every two hours. (B) In total, 66%and 33% of incidents occurred during the day and night, respectively, and 3% were unknown. (C) Within hospital sites, 58% and 42% of suicide attempts occurred during the day and night, respectively. Outside hospital sites, 75% and 19% of incidents took place during the day and night, respectively, and 6% were unknown.

Discussions

While suicide attempts in hospitals seem rare (Crammer, 1984), the prevalence rate in hospitalized patients is three times higher than that in the general population (Dhossche, 2001). As noted, completed suicide is the second most common adverse event in hospitals (Dhossche, 2001), and incidents typically result in the medical staff feeling guilty (Bowers, Banda & Nijman, 2010). Because previous studies have reported that psychiatric inpatients are at high risk for suicide (Appleby, 1992; Powell, 2000), and since there have been no studies on suicide attempts in psychiatric inpatients in Japan where the prevalence rate is very high, we retrospectively investigated the clinical characteristics of suicide attempts in psychiatric inpatients in the Nara prefecture over eleven years.

The results of our study are very similar to those from other countries (Elizabeth, David, Julia, et al., 2001; Proulx, Lesage & Grunberg, 1997). The male/female ratio was 1.5:1 in our study, which is similar to those in most previous studies (Elizabeth et al., 2001, Proulx et al., 1997). The most common psychiatric diagnoses were schizophrenia spectrum disorders (51.4%) followed by affective disorders (40%), which is also similar to those in previous reports (Proulx et al., 1997). These studies, including ours, suggest that clinicians should give more attention to suicide risk in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders and affective disorders.

With regard to the method used for suicide attempts, hanging was the most frequent means in nearly all reports, including ours (Elizabeth et al., 2001; Proulx et al., 1997), and seems to be a typical means of inpatient suicide. Similar to a previous report (Proulx et al., 1997), the rate of hanging in our study was much higher in hospital sites (79%) than outside of them (37.5%), indicating that hangings in hospital sites could possibly be prevented by removing likely means. Whereas one study suggests that the time during which the risk for suicide is the greatest is between the hours of 15:00–18:00 (Vollen, et al., 1975), another study shows that 08:00–12:00 is the riskiest period (Powell et al., 2000).

We had expected the risk of suicide attempts would increase during the night when fewer staff were working. However, our study revealed that only 31% (n=11) of all incidents occurred during the night (20:00–8:00) and more than double (66%; n=23), during the day (8:00–20:00). In addition, our investigation on the time and location of the incidents showed that suicide attempts occurred more frequently during the day than the night, regardless of whether they took place inside or outside hospital sites. These results suggest that even during the day when many staff can observe and care for inpatients, it is necessary to pay attention to the risk of suicide attempts. As for the tools used for hanging, towels and belts on doorknobs and bedside rails were the most common, seemingly due to their ease of access, even in locked wards. Therefore, removing towels and belts as much as possible, particularly within hospital sites, and refurbishing hospital rooms without doorknobs or bedside rails could possibly reduce the number of suicides among psychiatric inpatients.

Despite the compelling results from this study, there were some limitations that should be noted. First, this study relies on a small amount of data retrospectively collected through incident reports. Second, we were unable to assess some key information, for example length of stay and noted stressors. Finally, although we used data from several sites, our results cannot be generalized to all Japanese facilities. Therefore, an increased number of prospective samples in larger areas is needed to better delineate the characterization of suicide attempts in psychiatric inpatients. Although the ability to predict suicide accurately is limited, we may be able to prevent some fatal outcomes by understanding more characteristics of psychiatric inpatient suicide attempts.

Acknowledgement

We thank Mr. Kiyoshi Nishikawa for collecting data.

References

- Appleby, L. (1992). Suicide in psychiatric patients: Risk and prevention. British Journal of Psychiatry, 161, 749-758.doi:10.1192/bjp.161.6.749

- Bowers, L., Banda, T., &Nijman, H. (2010). Suicide inside: A systematic review of inpatient suicides. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 198, 315-328. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181da47e2

- CabinetOffice, Government of Japan (2013). Retrieved April 26, 2014, fromhttp://www8.cao.go.jp/jisatsutaisaku/toukei/h25.html

- Conwell, Y., Duberstein, P. R., Cox, C., Herrmann, J. H., Forbes, N. T., & Caine, E.D. (1996). Relationships of age and Axis I diagnoses in victims of completed suicide: a psychological autopsy study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 153, 1001-1008

- Crammer, J. (1984). The special characteristics of suicide in hospital in-patients. British Journal of Psychiatry, 145, 460-463.doi:10.1192/bjp.145.5.460

- Dhossche, D., Ulusarac, A., &Syed, W. (2001). A retrospective study of general hospital patients who commit suicide shorty after being discharged from the hospital. Archives of Internal Medicine, 161, 991-994.doi:10.1001/archinte.161.7.991

- Elizabeth,A., David, S., Julia, M., &Campbell, M. (2001).The Wessex recent in-patient suicide study, 2.case-control study of 59 in-patient suicides.BritishJournal of Psychiatry,178, 537-542.doi:10.1192/bjp.178.6.537

- Foster, T., Gillespie, K., &McCelland, R. (1997).Mental disorders and suicide in Northern Ireland.British Journal of Psychiatry, 170, 447-452. doi:10.1192/bjp.170.5.447

- Hawton, K., &Heeringen, K.(2009). Suicide. Lancet, 373, 1372-1381. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60372-X

- Isometsa, E., Henriksson, M., Marttunen, M., Heikkinen, M., Aro, H.,Kuoppasalmi, K., et al. (1995). Mental disorders in young and middle aged men who commit suicide. British Medical Journal, 310, 1366-1367.doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.310.6991.1366

- Mann, J. J., Apter, A., Bertolote, J., Beautrais, A., Currier, D., Haas, A., et al. (2005). Suicide prevention strategies: A systematic review.The Journal of the American medical Association, 26, 2064-2074.doi:10.1001/jama.294.16.2064

- National Police Agency. (2013). Retrieved April 26, 2014, fromhttp://www.npa.go.jp/toukei/index.htm Powell, J., Geddes, J., Deeks, J., Goldacre, M., &Hawton, K.(2000). Suicide in psychiatric hospital in-patients: Riskfactors and their predictive power. British Journal of Psychiatry, 176, 266-272. doi:10.1192/bjp.176.3.266

- Proulx, F., Lesage, A., &Grunberg, F. (1997).One hundred in-patient suicides.British Journal of Psychiatry, 171, 247-250.doi:10.1192/bjp.171.3.247

- TheJoint Commission.(2013). Sentinel eventstatistics.Retrieved April 26,2014, from http://www.jointcommission.org/SentinelEvents/Statistics/

- Vollen, K.H., &Watson, G.(1975).Suicide in relation to time of day and day of week?American Journalof Nursing, 75, 263

- World Health Organization (2013).Suicide prevention (SUPRE).Retrieved April 26, 2014, from http://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicideprevent/en/

Relevant Topics

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 15774

- [From(publication date):

March-2014 - Aug 31, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 10943

- PDF downloads : 4831