Short Communication Open Access

Suicide Prevention Education in Schools in Japan

Kenji Kawano*Center for Suicide Prevention, National Institute of Mental Health, National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, Tokyo, Japan

Visit for more related articles at International Journal of Emergency Mental Health and Human Resilience

Abstract

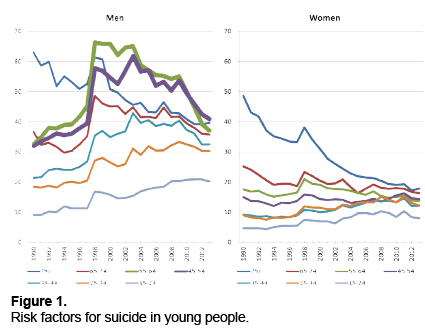

In Japan, suicide rates increased in all age groups in 1998, particularly in men aged 45 to 64 years. In recent years, suicide rates have decreased in middle-aged and the elderly, but the same cannot be said for those aged 15 to 34-years. According to the Cabinet Office, in 2014, the suicide rate for those in their 40s, 50s, and 60s was 23.0, 27.1, 24.5, respectively, showing a 32.9%, 39.6%, and 39.8% decrease from the 1998 rate, respectively. In contrast, the suicide rate for those in their 20s and 30s was 20.8 and 21.2, respectively, with a reduction rate of 14.4% and 19.1%, respectively. According to the data provided by the National Police Agency, work problems were the common cause of suicides in those in their 20s and 30s; however, more commonly, the cause was unknown. In other words, although suicide in young people is an urgent issue in Japan, there is a need for further research on its risk factors (Figure 1).

Risk Factors for Suicide in Young People

In Japan, suicide rates increased in all age groups in 1998, particularly in men aged 45 to 64 years. In recent years, suicide rates have decreased in middle-aged and the elderly, but the same cannot be said for those aged 15 to 34-years. According to the Cabinet Office, in 2014, the suicide rate for those in their 40s, 50s, and 60s was 23.0, 27.1, 24.5, respectively, showing a 32.9%, 39.6%, and 39.8% decrease from the 1998 rate, respectively. In contrast, the suicide rate for those in their 20s and 30s was 20.8 and 21.2, respectively, with a reduction rate of 14.4% and 19.1%, respectively. According to the data provided by the National Police Agency, work problems were the common cause of suicides in those in their 20s and 30s; however, more commonly, the cause was unknown. In other words, although suicide in young people is an urgent issue in Japan, there is a need for further research on its risk factors (Figure 1).

Approaches toward Upstream Prevention

“In contrast to risk factors, protective factors guard people against the risk of suicide. While many interventions are geared towards the reduction of risk factors in suicide prevention, it is equally important to consider and strengthen factors that have been shown to increase resilience and connectedness and that protect against suicidal behavior” (WHO, 2014). Implementation of the “upstream prevention approach” early in life is likely to lead to better adjustment. Consequently, it is important to identify a field for young people which would be appropriate to use the related protective factors as a preventive strategy.

In Japan, suicide prevention education in schools could be considered a promising approach for upstream prevention. In recent years, the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) have issued three booklets on suicide prevention in schools. These booklets on “Suicide prevention in children for teachers,” “emergency response guide for a suicide attempt by a child,” and “prevention of suicide in children-a guide for suicide prevention education in schools” are available from HP of MEXT. Based on these, the prerequisites, goals and content for suicide prevention education have been proposed. In future, exploratory research in this field is expected to accumulate evidence for the effectiveness of suicide prevention education.

A School based Suicide Prevention Program-GRIP

Several suicide prevention education programs have been developed abroad (Gould & Kramer, 2001). Similarly, we have developed a suicide prevention education program called GRIP, it stands for Gradual approach, Resilience, In a school setting, and Prepare scaffoldings (Shiraga et al., 2015). Based on a theoretical study, we assumed that the assistance provided to students with serious difficulties in the classroom needs to be based on four goals: understanding of feelings, expression of emotions, understanding and learning coping behavior, and understanding and experiencing consultation.

To achieve these goals, the GRIP program adopts group learning that included a workbook, a card game, and a DVD. By learning to provide support to a friend and to consult an adult in the class, the sense of belonging to the class is improved in each student, and their feeling of being a burden is reduced. That is, with reference to the interpersonal theory of suicide (Joiner et al., 2009), the GRIP program is assumed to lead to strengthening of the protective factors related to suicide. Feasibility studies have been conducted in several schools to examine the effectiveness of the GRIP program. The program has been found effective in reducing destructive expression, improving self-esteem, and intentionality of seeking support from adults (Shiraga et al., 2015)

In fact, the occurrence of suicide has led to an increase in the awareness of prevention of the same. However, by definition, the upstream prevention approach is implemented before the suicide occurs. Therefore, necessity is not always well accepted in the field. While safety management of students is an important issue, currently suicide prevention is not considered a high priority in Japanese schools. Therefore, in order to incorporate suicide prevention education in the regular school activities, and to develop a feasible suicide prevention education program, it is necessary to convince schools about the significance of the suicide prevention education. Discussions need to be conducted on the value of suicide prevention in Japanese schools, including the significance of reducing destructive expression and promoting support-seeking behavior, which are subindexes of the GRIP program. It would also be beneficial to learn from successful suicide prevention education programs being conducted in other countries

References

- Gould M.S., & Kramer R.A. (2001). Youth suicide prevention. Suicide Life Threat Behavior. 31, 6-31.

Shiraga, K. et al. (2015). The measurement for evaluation of suicide prevention education programs in junior high school. Suicide prevention and crisis ntervention, 36, 23-32. - Van Orden, K.A., Witte, T.K., Cukrowicz, K.C., Braithwaite, S., Selby, E.A., & Joiner, T.E. (2009). The interpersonal theory of suicide. American psychological association.

- WHO (2014). Preventing suicide: A global imperative, Accessed from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/suicide-prevention/world_report_2014/en/

Relevant Topics

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 18633

- [From(publication date):

specialissue-2015 - Aug 30, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 13792

- PDF downloads : 4841