Research Article Open Access

The Communication Attitude Test for Adults who Stutter (BigCAT): A Test-Retest Reliability Investigation among Adults who do and do not Stutter

Vanryckeghem M1* and Muir M21Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders, University of Central Florida, USA

2Department of Speech and Hearing, Melbourne Terrace Rehabilitation Center, Florida Ave, Melbourne, Australia

- *Corresponding Author:

- Martine Vanryckeghem

Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders

University of Central Florida

Scorpius Street, Orlando, USA

Tel: +1+407-823 4808

Fax: +1+407-823 4816

E-mail: martinev@ucf.edu

Received date: January 27, 2016; Accepted date: May 02, 2016; Published date: May 10, 2015

Citation: Vanryckeghem M, Muir M (2016) The Communication Attitude Test for Adults who Stutter (Big CAT): A Test-Retest Reliability Investigation among Adults who do and do not Stutter. J Speech Pathol Ther 1:110. doi: 10.4172/2472-5005.1000110

Copyright: © 2016 Vanryckeghem M et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Speech Pathology & Therapy

Abstract

Background: Stuttering within a multi-dimensional framework revolves around the recognition that affective, behavioral and cognitive variables play a role in the nature and persistence of the disorder. Aside from clinical observations, the value of self-report standardized measures to explore the ‘below the surface’ structures that go along with stuttering has been acknowledged by many workers in the field of fluency disorders. As it relates to the investigation of the cognitive correlate of stuttering, self-report tests exploring speech-associated attitude have been established. The Communication Attitude Test for Adults who Stutter (BigCAT) is one of the more recently developed standardized assessment tools that serves this purpose.

Aims: The aim of this investigation was to determine the BigCAT’s test-retest reliability.

Methods and Procedure: The BigCAT was administered to a group of 33 adults who stutter and 50 adults who do not stutter. All participants were given the test twice between 5 and 7 days apart.

Outcomes and Results: The test scores on the first and second administration of the BigCAT proved not to be statistically significantly different for both groups of participants. In addition, the correlations between the two BigCAT test scores were strong. As a side issue, it was observed that the scores of adults who do and do not stutter differed significantly on both occasions.

Conclusion and Implications: In addition to previous data that have pointed to the BigCAT’s usefulness in discriminating individuals who stutter from those who do not based on their speech-associated belief system, and the test’s internal reliability, the present study indicates that the BigCAT has good test-retest reliability.

Keywords

BigCAT; Communication attitude test; Speech-associated attitude; Stuttering; Stammering

Background

The viewpoint that not only the overt component of stuttering is characteristic of the person who stutters (PWS), but that other factors make up the totality of what constitutes a PWS has been generally accepted. By the time an individual who stutters reaches adulthood, the affective, behavioral and cognitive correlates of stuttering have grown due one’s experience history. The co-existing sequel of the disorder have intensified and crystallized and different experiences, one after another, have added to the complexity of the disorder. The contributory factors of the stuttering disorder relate to negative emotional reaction, anxiety and worry being evoked by particular sounds or words and/or different speech situations that are being dreaded, and frequently induce speech breakdown [1-6]. They might set the stage for the use of coping behaviors in anticipation of stuttering or to escape its occurrence [7]. These experiences often lead to negative thoughts and create a negative speech-associated attitude [8-11].

These inner components that accompany stuttering are best explored through introspection and serve to augment the observations made by the clinician [12,13]. Aside from making use of interviews, the most systematic way to search for the intrinsic features that accompany stuttering involves the administration of self-report measures. Starting around the middle of the 1900’s, various qualitative and quantitative attempts have been made by clinicians and applied researchers to assess and compare the attitude of PWS to those who do not stutter (PWNS) [14-16]. Of the test procedures currently available for adults, few make it possible to inventory communication attitude in a way that is un-confounded by elements that explore other concomitants of stuttering that are more affective and behavioral in nature. This is not to ignore that the affective (A), behavioral (B) and cognitive (C) dimensions that are accessory to the stuttering itself are interrelated [12,17,18] and have an overall impact on a person’s quality of life [19]. However, some models describe these ABC’s in a molar, others in a more molecular, denotative and typographical way [20].

Among the first who attempted to assess the cognitive component of stuttering, as part of the ABC tripartite model, was Erickson (1969) whose S-Scale and subsequent S-24 revision [21,22]. Contain statements that make no reference to dysfluency, and allowed for comparison of the attitudinal reactions of PWS and PWNS. Despite the notable difference in the means of the two groups, their distributions showed considerable overlap. This finding led Erickson to suggest that, while the communication attitudes of PWS and PWNS differ, they do so "primarily in degree" (p.722) rather than in a dichotomous way. He noted that it “emphasizes … our urgent need for a greater variety of refined and standardized techniques for diagnosing and assessing" (p. 722) those who stutter.

The Erickson S-24 has long been the predominant instrument for measuring speech-associated attitude among PWS. However, research has suggested that the internal validity of the S-24 items can be questioned [17]. Moreover, as mentioned earlier, the S-24 results comparing PWS to PWNS, though statistically significant show notable overlap.

Given the above information, the fact that the original Erickson scale was designed close to 50 years ago, and some of its items have been outdated, stimulated the development of the Communication Attitude Test for Adults who Stutter (BigCAT) [11], as a component of the Behavior Assessment Battery for Adults who Stutter [21]. It was designed to determine the presence, and extent of, mal-attitude toward speech among adults who stutter. Data from the [11] study have shown that the BigCAT is a useful tool in differentiating PWS from PWNS based on their speech-associated attitude. More specifically, the mean score for PWS was 6 standard deviations above that of PWS and the effect size of 5.36 can be considered very large. In addition, analysis of its items indicated that the BigCAT has good internal consistency (Cronbach Alpha .89 and .86 for PWS and PWNS).

In a follow-up investigation comparing the BigCAT with the Erickson S-24, it was revealed that the overlap in the scores of PWS and PWNS was greater for the Erickson S-24 than it was for the BigCAT [23]. In addition, the effect size was larger for the BigCAT (4.98) than it was for the Erickson S-24 (2.73), indicating that the BigCAT seemed to be the more powerful of the two instruments assessing speech-associated attitude.

What has yet to be determined was the consistency with which participants answer questions on the BigCAT. Consequently, the present study was designed to determine the BigCAT’s test-retest reliability.

Methods and Procedure

Participants

Thirty-three stuttering and 50 non stuttering adults were administered the Communication Attitude Test for Adults who Stutter (BigCAT) (Brutten & Vanryckeghem, 2011). The age for the PWS sample ranged from 18 to 54 (mean age: 29) and from 18 to 58 for the PWNS (mean age: 34). Twenty-one of the PWS were male and 12 were female. The PWNS population included 22 males and 28 females.

The participants who stutter were selected from clinics and private practices across the USA. Fifty-seven percent of the participants reported their stuttering onset to be between the ages of two and six, whereas 19% reported an onset between ages six and twelve. The remaining participants (24%) reported they could not recall the exact onset of their stuttering, but mentioned that it was sometime during childhood. Three percent of the PWS received a doctorate degree, 24% held a master’s degree, 32% achieved a bachelor’s degree, 3% received an associate’s degree, and 38% reported having a high school diploma. Only two out of the 37 participants in the PWS group claimed to have a concurrent speech problem, both related to voice issues, more specifically, bilateral VF edema and a paralyzed vocal fold. One participant reported receiving previous speech treatment for articulation /r/ in elementary school. Each participant was given a severity rating by their clinician using a five-point scale. Nineteen percent were considered to be very mild, 30% were rated as mild, 19% were given a rating of moderate, 21% were deemed severe, and 11% were classified as very severe.

The sample of PWNS also came from different regions in the United States. None of the PWNS indicated a current speech and/or language disorder. Four out of the 50 participants reported receiving previous speech/language treatment for reading, writing, articulation, and a dialectal difference. According to the demographic questionnaire, 10% reported earning a master’s degree, 28% received a bachelor’s degree, 20% held an associate’s degree, 4% attended vocational school, and 34% had a high school diploma.

Procedure

Each participant was instructed to determine whether the 35 statements that make up the BigCAT were ‘True or False’ as far as their own speech is concerned. The directions for the assessment were verbally presented, as the subjects read along silently. After the instructions had been given, the participants were asked whether or not they had any questions. If so, these were addressed prior to the participant being allowed to begin completing the self-report test. Answers implying a negative speech-associated attitude received a score of 1, and positive responses were scored 0, resulting in possible scores ranging from 0 to 35. All participants were given the BigCAT on two different occasions, no longer than a week and no fewer than five days apart. The participants were not informed in advance that they would be completing the assessment twice.

Each participant in the PWS group was individually administered the BigCAT by their clinician. All clinicians received a letter in advance outlining specific instructions to be followed for correct test administration. The participants in the PWNS group received the test instructions for the BigCAT from the senior author or a graduate research assistant who had been trained to properly administer the self-report test. Also this group of participants filled out the questionnaire individually.

Outcomes and Results

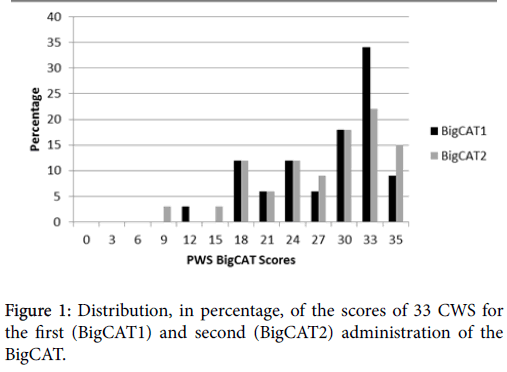

As described in Table 1, the average scores obtained on the first and second administration of the BigCAT (BigCAT1 and BigCAT2) by PWS were 27.03 (SD=6.44) and 26.18 (SD=7.01). In addition, the median scores obtained for BigCAT1 and BigCAT2 were 29 and 28, and the mode was 33 and 28. As made evident by the score distributions in Figure 1, the scores on BigCAT1 ranged from 10 to 34, a range almost identical to the BigCAT2 scores, between 9 and 35.

| BigCAT 1 | BigCAT 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PWS | PWNS | PWS | PWNS | |

| Mean | 27.03 | 4.22 | 26.18 | 4.06 |

| Stand. Dev. | 6.44 | 3.76 | 7.01 | 3.78 |

| Median | 29 | 3 | 28 | 3 |

| Min. | 10 | 0 | 9 | 0 |

| Max. | 34 | 15 | 35 | 14 |

Table 1: Measures of Central Tendency and Variation on the First and Second BigCAT Administration (BigCAT 1 and 2, respectively) for PWS and PWNS.

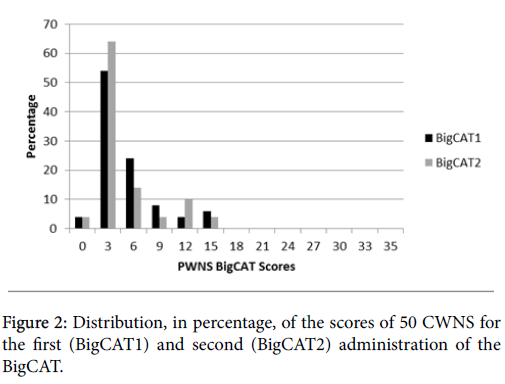

The data obtained from PWNS resulted in an essentially identical mean score for BigCAT1 and BigCAT2 of 4.22 and 4.06, with a standard deviation of 3.76 and 3.78. The median and modal scores were 3 and 2 for both administrations. The score distributions (Figure 2) show that the range of scores was 0 to 15 for BigCAT 1, and 0 to 14 for BigCAT 2, out of a total score of 35.

The purpose of the current study was to establish whether or not the scores obtained for BigCAT1 and BigCAT2 showed stability when administered up to 1 week apart. The average BigCAT1 and BigCAT2 scores of PWS were proven not to be significantly different (t=1.129; p=.267). Neither did the BigCAT1 and BigCAT2 mean scores for PWNS differ (t=.429, p=.670). The Pearson correlation between the two test administrations was .80 for the PWS, and for the PWNS it was .76.

Although not the purpose of the study, as a tangential issue in this investigation, the scores of the PWS and PWNS were compared in order to see whether or not they confirm previous comparative data with the BigCAT. In this investigation, the mean BigCAT1 and BigCAT2 scores of PWS were 6 SD elevated over those of PWNS. Once again, the means of the two groups of participants differed significantly for the first (t=19.319, p=.000) as well as the second test administration (t=17.837, p=.000).

Conclusions and Implications

The above results add important information to the already present data on the BigCAT, which indicated that this instrument is a powerful tool in discriminating adults who do and do not stutter based on their speech-associated attitude, given the fact that the average PWS score fell 6 standard deviations above that of PWNS [11]. The current data add to the usefulness of the BigCAT to the extent that they indicate the consistency and positional stability of the test scores over repeated test administration. The test-retest reliability results mirror those of an investigation with the Communication Attitude Test for School-age Children (CAT) pointing to a test-retest reliability of .83 following a hiatus of one week between repeated testing [24]. The current data, together with the high internal reliability results (.89 and .86 for PWS and PWNS) [11], add weight to the fact that the BigCAT is a reliable test exploring the extent to which negative attitudes play a role in the disorder faced by PWS. As such, it can be considered a useful addition to the Behavior Assessment Battery for Adults who Stutter [24], and is a supplement to the already existing assessment instrument options available to speech-language pathologists interested in a multidimensional evaluation of their adult client who stutters.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the individuals who participated in this study and the Board Certified Fluency Specialists who assisted with this investigation.

References

- Cooper E (1999) Is stuttering a speech disorder? ASHA 10: 11.

- Craig A, Tran Y (2014) Trait and social anxiety in adults with chronic stuttering: Conclusions following meta-analysis. Journal of Fluency Disorders 40: 35-43.

- Ezrati-Vinacour R, Levin I (2004) The relationship between anxiety and stuttering: A multidimensional approach. Journal of Fluency Disorders 29: 135-148.

- Guitar B (2014) Stuttering: An integrated approach to its nature and treatment (4th edn). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Iverach L, Rapee RM (2014) Social anxiety disorder and stuttering: Current status and future directions. Journal of Fluency Disorders 40: 69-82.

- Manning W (2010) Clinical decision making in fluency disorders (3rd edn). Clifton Park NY: Delmar Cengage Learning.

- Vanryckeghem M, Brutten G, Uddin N, Van Borsel J (2004) A comparative investigation of the speech-associated coping responses reported by adults who do and do not stutter. Journal of Fluency Disorders 29: 237-250.

- Barber Watson J (1995) Exploring the attitudes of adults who stutter. Journal of Fluency Disorders 28: 143-164.

- Erickson R (1969) Assessing communication attitudes among stutterers. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research 12: 711-724.

- Iverach L, Menzies R, Jones M, O’Brian S, Packman A, et al. (2011) Further development and validation of the Unhelpful Thoughts and Beliefs About Stuttering (UTBAS) scales: relationship to anxiety and social phobia among adults who stutter. Int J Lang CommunDisord 46: 286-299.

- Vanryckeghem M, Brutten G (2011) The BigCAT: A normative and comparative investigation of the communication attitude of stuttering and nonstuttering adults. Journal of Communication Disorders 44: 200-206.

- Barber Watson J (1988) A comparison of stutterers’ and nonstutterers’ affective, cognitive, and behavioral self-reports. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research 31: 377-385.

- Perkins W (1990) What is stuttering. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders 55:370-382.

- Ammons R, Johnson W (1944) Studies in the psychology of stuttering: XVIII. The construction and application of a test of attitude toward stuttering. Journal of Speech Disorders 9: 39-49.

- Brown SF, Hull HC (1942) A study of some social attitudes of a group of stutterers. Journal of Speech Disorders 7: 323-324.

- Johnson W (1952). Form 14: "Stutterers' self-ratings of reactions to speech situations". In W. Johnson, F. Darley & D. Spriestersbach, Diagnostic manual in speech correction (151-152). New York: Harper and Brothers.

- Brutten G, Vanryckeghem M (2003) Behavior Assessment Battery: A multi-dimensional and evidence-based approach to diagnostic and therapeutic decision making for adults who stutter. Destelbergen Belgium: StichtingIntegratieGehandicapten&Acco Publishers.

- Vanryckeghem M (2008) People who stutter: A view from within. California Speech-Language-Hearing Association 37: 9-10, 20.

- Yaruss JS, Quesal R (2006) Overall Assessment of the Speaker’s Experience of Stuttering (OASES): Documenting multiple outcomes in stuttering treatment. Journal of Fluency Disorders 31: 90-115.

- Franic DM, Bothe AK (2008) Psychometric evaluation of condition-specific instruments used to assess health-related quality of life, attitudes, and related constructs in stuttering. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 17: 60-80.

- Vanryckeghem M, Brutten G (in press) Behavior Assessment Battery for Adults who Stutter. San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing, Inc.

- Andrews G, Cutler J (1974) Stuttering therapy: The relationship between changes in symptom level and attitudes. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders 39: 312-319.

- Vanryckeghem M, Brutten G (2012) A Comparative investigation of the BigCAT and Erickson S-24 measures of speech-associated attitude. Journal of Communication Disorders 45: 340-347.

- Vanryckeghem M, Brutten G (1992) The Communication Attitude Test: A test-retest reliability investigation. Journal of Fluency Disorders 17: 177-190.

Relevant Topics

- Stuttering therapy

- Active listening

- Aphasia

- Articulation disorders:

- Autism Speech Therapy

- Bilingual Speech pathology

- Clinical Linguistics

- Communicate Speech pathology

- Interventional Speech Therapy

- Late talkers

- Medical Speech pathology

- Spectrum Pathology

- Speech and Language Disorders

- Speech and Language pathology

- Speech Impediment / speech disorder

- Speech pathology

- Speech Therapy

- Speech Therapy Exercise

- Speech Therapy for Adults

- Speech Therapy for Children

- Speech Therapy Materials

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 16572

- [From(publication date):

June-2016 - Aug 31, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 15361

- PDF downloads : 1211