Research Article Open Access

Using Aggregate Data on Health Goals, Not Disease Diagnoses, to Develop and Implement a Healthy Aging Group Education Series

Lamarche L1*, Oliver D1,2, Cleghorn L1, Werstuck MMD1,2, Pauw G1,2, Bauer M1,2, Doyle L1,2, Colleen McPhee1,2, O’Neill C1,2, Guenter D1,2, Winemaker S1,2, White J1,2, Price D1,2 and Dolovich L11Department of Family Medicine, McMaster University, Hamilton ON, Canada

2McMaster Family Health Team, Hamilton ON, Canada

- Corresponding Author:

- Larkin Lamarche

Research Associate, Department of Family Medicine

David Braley Health Sciences Centre

100 Main Street West, 5th Floor

Hamilton ON L8P 1H6, Canada

Tel: 905.525.9140

E-mail: lamarche@mcmaster.ca

Received Date: June 20, 2017; Accepted Date: July 13, 2017; Published Date: July 17, 2017

Citation: Lamarche L, Oliver D, Cleghorn L, Werstuck MMD, Pauw G, et al. (2017) Using Aggregate Data on Health Goals, Not Disease Diagnoses to Develop and Implement a Healthy Aging Group Education Series. J Community Med Health Educ 7:535. doi: 10.4172/2161-0711.1000535

Copyright: © 2017 Lamarche L, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Community Medicine & Health Education

Abstract

Background: The Healthy Aging Group Education Series was developed by interprofessional primary healthcare team and researchers to address the health needs and goals of nutrition, fitness and function, and advance care planning identified using data from a randomized controlled trial.

Methods: Older adults from one family practice were invited to attend the series and participate in the descriptive evaluation. The series was developed based on aggregated patient-reported data on health goals; risks and needs gathered using a structured process. Surveys which included open-ended feedback and rated items of content and delivery evaluated the series. Program delivery expenses were itemized.

Results: Of 69 people invited, a range of 26 to 37 people attended sessions. The overall series was rated positively with respect to meeting attendees’ expectations and being well-organized; 69.2% and 76.9% of attendees gave a positive rating respectively. Individual session feedback indicated a range of positive ratings (82.8-100%) for categories of effective and engaging presenters and providing new and relevant information. The majority of attendees (76.9%) indicated they would recommend the series to friends. The series continues to be offered regularly in the family practice.

Conclusion: Unlike other types of group care, health goal information (and not disease diagnoses) was used to develop and deliver the program.

Keywords

Older adults; Health goals; Primary care; Group education; Interprofessional healthcare

Introduction

Using aggregate data on health goals, not disease diagnoses, to develop and implement a healthy aging group education series.

Healthcare systems are not well designed to maintain or improve the health of individuals [1-3]. Much of our healthcare system uses processes that are reactive and not proactive or preventative [4]. People who may seem well or may not have an obvious morbidity can benefit from strategies to prevent decline. Creating systems that focus on people well have benefits for individuals, communities and the overall healthcare system. The primary healthcare system is in need of novel care models that leverage interprofessional team members to provide alternatives to physician-centred care. In diabetes care for example, alternative care models [5-8] have been explored as approaches outside of traditional physician-led visits [9]. Group medical visits, selfmanagement education and group education have been increasingly popular. These approaches can to improve efficiency and encourage patient self-management across a variety of patient groups [10-21].

The concept of leveraging aggregate data compliments the approach of delivering care to groups of patients with shared needs. Using such data to identify care gaps does not detract from individuality but rather adds another dimension, as individuals benefit from the guidelines developed for the populations to which they belong as well as the sharing of peer-to-peer experience that group visits are based upon [22]. Although group medical visits have been fairly common in delivering care across people with shared care medical needs, this approach has been relatively limited to shared chronic disease diagnoses and is not necessarily focused on prevention nor on groups of patients who may be considered “well”. Addressing patient priorities and goals effectively is increasingly a focus of discussion in primary care. Interprofessional primary care teams are well suited to rise to the challenge of identifying and responding to goals of well, yet at-risk, patients. Doing this in a cost-effective manner will be important. This program used aggregate health information and health goals to develop and implement a group educational series (Healthy Aging Group Education Series; Healthy AGES). It was developed with the intention that it could be adapted based on updated data.

Methods

The idea of the Healthy AGES organically emerged from the review of aggregate data from a study to evaluate the effectiveness of the Health TAPESTRY approach in partnership with the McMaster Family Health Team (MFHT). Health TAPESTRY is an approach that centres on meeting a person’s health goals and health needs explicitly gathered with the support of technology, community volunteers, an interprofessional team, system navigation, and better links between primary care and community organizations [23]. The data on health goals indicated that participants wanted to stay or become more physically active, stay socially connected, managing chronic conditions, stay at home, and improve dietary habits. The data on health needs and risks were also examined and showed that nutrition, fitness and function, and advance care planning (ACP) were areas identified as topics to be addressed (Table 1).

| Information | Proportion of sample |

|---|---|

| A fall in the last year | 23.9% |

| Five or more medications | 28.4% |

| Urinary incontinence | 36.3% |

| Nutritional risk | 41.3% |

| Sub-optimal physical activity | 80.6% |

| Abnormal clock | 68.1% |

| Wants a discussion about advance care planning | 59.2% |

Table 1: Needs, alerts and key information reviewed (based on initial 201 client responses).

Key healthcare providers were invited to address the topics as working groups. The format agreed upon included an introductory session, then a 2-hour session for each topic, with one topic per week. Each session had learning objectives, an agenda, and activities. The introductory “teaser” session would review the concept of the series and be used to gather targeted information about the three topics from attendees. A survey was developed by the working groups and allowed attendees to indicate specific areas of interest for nutrition, fitness and function, and ACP. For each topic, attendees were also asked to list two questions they wanted to ask experts (Table 2 for intake questions and summary answers gathered for planning the series).

| Teaser | Nutrition | Fitness and Function | Advance care planning | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Session title | Health Aging through Healthy Living | Take a Bite out of Nutrition! | Is Vacuuming Enough? | Your Last Transition…Doing it Well |

| Number of clients who responded to invitation (proportion) | 50 (72%) | 44 (64%) | 46 (67%) | 47 (68%) |

| Attendance | 30 | 26 | 33 | 35 |

| Members on working groups | 2 family doctors 2 registered dieticians 1 research coordinator from Health TAPESTRY |

2 registered dieticians 1 research coordinator from Health TAPESTRY |

2 occupational therapists 2 physiotherapists 1 research coordinator from Health TAPESTRY |

2 family doctors Co-lead 1 Palliative Care Physician 1 registered nurse 1 research coordinator from Health TAPESTRY |

| Intake survey questions | Not Applicable | Indicate which of the 7 common questions related to nutrition and aging in which you are interested: Nutrition and decreased appetite Weight issues and age Changes in appetite and how food tastes with age Nutrients for maintaining muscle mass and preventing falls Supplements Food to help with slow bowels Preventing malnutrition |

Identify barriers to exercise you experience and the areas you are most interested in learning about: Community programs Things to do to stay healthy Keeping active in the winter Any other topics you are interested in learning about related to fitness and function. |

Define advance care planning in your own words Identify if you know who your decision-maker is in the event you could not speak for yourself Identify things you have done related to advance care planning including making a will, identifying your power of attorney, having end-of-life conversations with your circle of care, and making those wishes known to your circle of care and your doctor. |

| Not Applicable | 95% wanted to know about nutrients 95% wanted to know about supplements Losing weight Medications and food |

48% wanted to learn about community programs 62% wanted to know some ways to stay active in the winter 62% wanted to learn about things to do to stay healthy Most common barrier was pain (38%) |

100% has a will 95% know who speaks for me if I am unable 85% has identified a Power of Attorney 60% has had conversations with family 50% has made wishes known to circle of care 5% has made wishes known to family physician |

|

| Number of clients responding to intake survey (proportion) | 22 (73%) | 21 (70%) | 20 (67%) | |

| Session learning objectives | Definition of health aging Introduction to each of the 3 planned topics |

Nutrient needs for older adults How to get enough protein Staying healthy by building stronger bones and preventing falls Common challenges |

Learning how much activity is needed to do to stay healthy? Being active in the winter |

Definition of advance care planning Reasons to develop a plan Components of an advance care planning (5 steps of advance care planning) |

| Session agenda | Presentation | Presentation Truth or myth exercises about food information Activity: reading food labels Activity: recognizing serving size |

Presentation | Presentation Small group discussion |

| Session materials/space considerations | Package with presentation slides Intake survey Pen Note pad Pedometer and step log Large classroom with screen |

Package with presentation slides Food label examples Plastic examples of serving sizes Large classroom with screen |

Package with presentation slides Walking poles Hand weights/therabands 7 chairs with backs Stop watch Large classroom with screen 3 small breakout rooms |

Package of presentation slides Copies of Speak Up Canada material |

Table 2: Summary of information gathered for planning and implementation for each session.

To meet individual patient needs, working groups were encouraged to use information from the intake survey prior to their session. The working groups were responsible to develop session content and any activities to foster learner engagement. A researcher was present in each working group to help maintain a unified focus around the series as a whole and bring the Health TAPESTRY perspective were necessary. Working groups met at least once in person, and then refined their session over email or informally in-person at the clinic.

The Health TAPESTRY research team was responsible for logistical considerations and costs of the series. The location of the series was Stonechurch Family Health Centre, a clinic within MFHT, which had free patient overflow parking (located about one block away from the clinic). A shuttle was available in anticipation of any mobility issues from the parking lot or poor weather. Hospitality ideas such as a registration table, an information package, signage, a greeter, refreshments, text size of handouts, and the use of a microphone were also considered. The series was developed in such a way to consider sustainability; it was flexible enough to address future areas of focus based on new, incoming aggregate data.

Evaluation

Rating of the overall event was completed as well as rating of how well each presentation provided relevant information, new information, and if the information was presented engagingly and effectively. Key messages attendees took away from the session were solicited. Informal feedback was solicited from the presenters. The cost of series and potential cost saving strategies were recorded. Research and program costs were separated.

Results

Invited individuals (N=69) were 70 years of age or older, community-dwelling and rostered within the MFHT who were the first group of intervention participants in the Health TAPESTRY study 23; control participants were not invited so as not to interfere with the main study. Of the people invited, 26-37 people attended sessions of the series. The average response rate to the invitation was 68%. Table 2 summarizes planning information of each session as well as identifies the interprofessional team members who comprised the working groups. A summary of information from implementation including attendance is shown in Table 2.

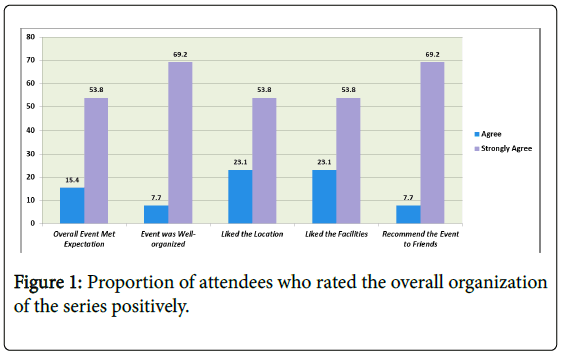

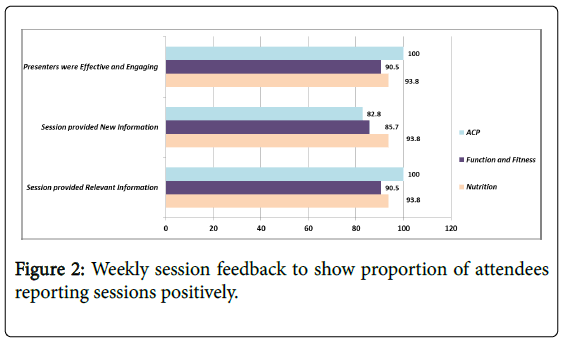

Notably, the learning objectives link to the results of the intake survey. The response rate to the evaluation form was 43% (teaser), 62% (nutrition), 75% (fitness/function), and 78% (ACP). The majority of attendees rated all aspects of the series positively (Figures 1 and 2). Commonly reported key messages included: the importance of eating proper food, sharing end-of-life desires with the one’s circle of care, including their family doctor, and the need to keep moving. Attendees suggested running the series in retirement homes. Presenters suggested holding recurrent sessions, providing information about community programs related to the topics and noting that the series should be open to all seniors within MFHT, not only those in Health TAPESTRY.

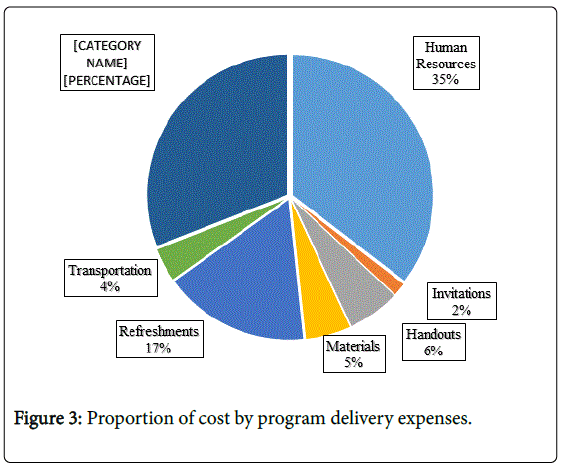

Costs for developing and implementing Healthy AGES are shown in Figure 3. Research costs were $3,193.98. The total program cost for initial development and implementation was $7,126.72, with the majority of costs related to human resources. The cost estimate of a second offering of the same series was $5,788, assuming less development costs as well as considering one-time costs.

This type of program can be offered at a much lower cost by reducing or eliminating several items (i.e., shuttle service, pedometers, food/beverages, full-colour materials, fewer providers involved). We believe the series could still meet its objectives by having one family doctor, one registered dietitian, and one physiotherapist/occupational therapist involved. Considering all cost saving strategies, we estimate it would cost $1,025 per series offering.

Discussion

A healthcare approach using aggregate health information and health goals was used to develop and implement a group educational series. Overall, the series was perceived positively by both attendees and presenters. Strengths and challenges are discussed.

Strengths

Additional expertise was not required as development leveraged existing knowledge within the clinic. Secondly, bundling sessions together as “healthy aging” allowed multiple domains of aging to be addressed. Development was done in such a way that translated findings from a research study directly into clinical practice. Using the information from a large RCT to assess health goals and needs allowed for the identification of potential topics, then content of each session was augmented based on the intake survey, allowing for the series to address individual needs. It married findings from aggregate data with individual-based data collected at the first session. However, unlike other types of group care, health goal data (and not disease diagnoses) was used. This approach may push the healthcare system’s focus on being proactive about health concerns, as well as group individuals based on function versus disease.

Positive by-products

Using aggregate data allowed for the identification of client needs that the clinic was either unaware of or had not systematically figured out how to address. Incontinence, for example, was one common health issue identified in the RCT, but it was decided not to initially include within the series. Identifying who and how to address the topics of nutrition, fitness and function and ACP was easier than identifying who and how to address incontinence in a group format. However, the process of developing the Healthy AGES was done in such a way to account for the addition of new topics. This process could also easily engage community leaders to address any topics that might be more efficiently addressed using resources outside the clinic walls.

Promoting sense of connection to the clinic was another positive by-product. Although not measured specifically, it is possible that individuals attending the Health AGES felt a closer connection to members of their healthcare team and to other patients sharing similar health needs and health goals. Getting the healthcare team out of their office environment and interacting with groups of patients can promote a sense of community and connectedness with the clinic.

Challenges

To address the multidimensionality of healthy aging, a variety of disciplines was required. Ensuring the message was consistent across sessions was challenging albeit not impossible. Commitment from clinic leadership is essential to allow for time to develop the series and space to run the sessions. Also, finding a balance between population and individual care goals is difficult. Healthy AGES did not by any means replace the need for individual care but instead offered complementary care to a group of healthy seniors on topics that are often not addressed in usual clinical practice yet extremely important for health.

Our team found it challenging to “categorize” the Healthy AGES within the literature. A core feature of this program was education to target knowledge, akin to group education and group medical visits 12. However, unlike group medical visits, medical assessment in any form were not completed. Part of the difficulty in categorizing Healthy AGES is that there is no standard approach to such group care models 12,19. Perhaps all types of models have a purpose depending on the needs of the patients.

Limitations

Limitations to the evaluation design should be noted. Assessment of face validity of the surveys was done through team review; no other validation of the survey was completed. Further, no pre-measures of outcomes were measured, thus, the impact of the Health AGES on outcomes (i.e., knowledge, behaviour), including objective measures (i.e., body composition, muscle strength), is unknown. It should also be noted that the purpose of the study was not to determine effectiveness, but rather understand the process of developing a series using aggregate data on health goals and needs; thus, the sample size is small. Future research should include effectiveness measures, particularly those which are validated, to provide evidence of this type of care model and help to support the need for sustainability. A larger sample size as well as a comparison group are critical. In addition, modifying variables including learning style or cognitive capacity, may influence how an individual experiences the Health AGES.

Considerations for sustainability

Healthy AGES was a series developed and implemented as a partnership between the Health TAPESTRY research team and members of MFHT. Offering the series regularly requires the consideration of clinic resources and work flow. Working closely with the MFHT from the start allowed for such factors to be considered, however, some costs need to be reduced for the clinic to offer the Health AGES consistently. The goal was to develop the materials and a process to develop content in a way that was reproducible by the clinic and transferable to the clinic workflow. In essence, by handing over all materials and the process outline, the clinic could run the series on its own. Considering cost savings, we estimate that the Healthy AGES would cost approximately $1,025 per offering. This amount does not consider what the clinic could bill. Further, using aggregate health goal and need information requires a database that can be used by the clinic. Because MFHT was a key implementation site for Health TAPERSTRY, this database was readily available. With minimal support from the research team, MFHT is currently running Healthy AGES as an ongoing program, with an added topic of brain and bladder function, a sign of its potential sustainability.

Acknowledgements and Funding

Acknowledgements

We would also like to acknowledge the clinic and research staff that made the Health AGES possible and continue to dedicate time and energy to its current form.

Source of funding

Health TAPESTRY was funded by Health Canada, with additional support from the Government of Ontario (MOHLTC), Labarge Optimal Aging Initiative, McMaster Family Health Organization, and the Department of Family Medicine at McMaster University.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Policy Paper (2010) Patient-Centred Care. Ontario medical association.

- (2011) Health Care Cost Drivers: The facts. Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI).

- Lewis S (2015) A system in name only-access, variation, and reform in Canada's provinces. N Engl J Med 372:497-500.

- Tinetti ME, Fried TR, Boyd CM (2012) Designing health care for the most common chronic condition multimorbidity. JAMA 307:2493-2494.

- Davidson MB (2007) The effectiveness of nurse and pharmacist-directed care in diabetes disease management: A narrative review. Curr Diabetes Rev 3: 280-286.

- Litaker D, Mion L, Planavsky L, Kippes C, Mehta N, et al. (2003) Physician nurse practitioner teams in chronic disease management: The impact on costs, clinical effectiveness and patients' perception of care. J Interprof Care 17:223-237.

- Parchman ML, Pugh JA, Romero RL, Bowers KW (2007) Competing demands or clinical inertia: The case of elevated glycosylated hemoglobin. Ann Fam Med 5:196-201.

- Taylor CB, Miller NH, Reilly KR, Greenwald G, Cunning D, et al. (2003) Evaluation of a nurse-care management system to improve outcomes in patients with complicated diabetes. Diabetes Care 26:1058-1063.

- Davis AM, Sawyer D, Vinci L (2008) The potential of group visits in diabetes care. CliDiab26:58-62.

- Clancy DE, Cope DW, Magruder KM, Huang P, Wolfman TE (2003) Evaluating concordance to american diabetes association standards of care for type 2 diabetes through group visits in an uninsured or inadequately insured patient population. Diabet Care 26:2032-2036.

- Hollander SA, McDonald N, Lee D, May LJ, Doan LN, et al (2015) Group visits in the pediatric heart transplant outpatient clinic. Pediatr Transplant 19:730-736.

- Jaber R, Braksmajer A, Trilling J (2006) Group visits for chronic illness care: Models, benefits and challenges. Family practmanang 13:37-40.

- Masley S, Sokoloff J, Hawes C (2000) Planning group visits for high-risk patients. Family practice manag7:33-37.

- Miller D, Zantop V, Hammer H, Faust S, Grumbach K (2004) Group medical visits for low-income women with chronic disease: A feasibility study. J women's health 13:217-225.

- Moitra E, Sperry JA, Mongold D, Kyle BN, Selby J (2011) A Group medical visit program for primary care patients with chronic pain. Prof Psychol-Res Pr 42:153-159.

- Pastore LM, Rossi AM, Tucker AL (2014) Process improvements and shared medical appointments for cardiovascular disease prevention in women. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract 26:555-561.

- Trento M, Passera P, Borgo E, Tomalino M, Bajardi M, et al (2004) A 5-year randomized controlled study of learning, problem solving ability, and quality of life modifications in people with type 2 diabetes managed by group care. Diabetes Care 27:670-675.

- Beck A, Scott J, Williams P, Robertson B, Jackson D, et al. (1997) A Randomized trial of group outpatient visits for chronically Ill older HMO members: The Cooperative - Health Care Clinic. JAGS 45:543-549.

- Barud S, Marcy T, Armor B, Chonlahan J, Beach P (2006) Development and implementation of group medical visits at a family medicine center. AJHP 63:1448-1452.

- Levine MD, Ross TR, Balderson BH, Phelan EA (2010) Implementing group medical visits for older adults at group health cooperative. J AmeGeriatSoc 58:168-172.

- Ciccone MM, Aquilino A, Cortese F, Scicchitano P, Sassara M, et al. (2010) Feasibility and effectiveness of a disease and care management model in the primary health care system for patients with heart failure and diabetes (Project Leonardo). Vasc Health Risk Manag6:297-305.

- Halpern R, Boulter P (2000) Population-based health Care: Definitions and Applications. Tufts Managed Care Institute.

- Dolovich L, Oliver D, Lamarche L, Agarwal G, Carr T, et al. (2016) A protocol for a pragmatic randomized controlled trial using the health teams advancing patient experience: Strengthening quality (Health TAPESTRY) platform approach to promote person-focused primary healthcare for older adults. Implement Sci11:49.

Relevant Topics

- Addiction

- Adolescence

- Children Care

- Communicable Diseases

- Community Occupational Medicine

- Disorders and Treatments

- Education

- Infections

- Mental Health Education

- Mortality Rate

- Nutrition Education

- Occupational Therapy Education

- Population Health

- Prevalence

- Sexual Violence

- Social & Preventive Medicine

- Women's Healthcare

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 9001

- [From(publication date):

August-2017 - Aug 13, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 8087

- PDF downloads : 914