Review Article Open Access

Structure and Implementation of United States Biological Export Control Policy

Michael A. Bailey1*, George W. Christopher1 and John C. David2

1Transformational Medical Technologies, JPEO-Chemical and Biological Defense, Fort Belvoir, VA, USA

2The Tauri Group, Alexandria, VA, USA

- *Corresponding Author:

- Michael A. Bailey

Transformational Medical Technologies

JPEO-Chemical and Biological Defense

Fort Belvoir, VA, USA

E-mail: michael.a.bailey132.civ@mail.mil

Received Date: August 17, 2012; Accepted Date: September 25, 2012; Published Date: September 27, 2012

Citation: Bailey MA, Christopher GW, David JC (2012) Structure and Implementation of United States Biological Export Control Policy. J Bioterr Biodef 3:118. doi:10.4172/2157-2526.1000118

Copyright: © 2012 Bailey MA, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Bioterrorism & Biodefense

Abstract

Treaties governing the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction in general, and biological weapons specifically, derive their value from the norms set forth in their articles. They provide a common starting point for signatory nations as they traverse the complex world of dual-use technologies and transfer of potentially dangerous materials. Treaties, however, are not enforceable regulations. Such regulations are developed separately, and are codified into law by the controlling authorities within national governments. This review will analyze the structure, implementation and administration of the United States’ export controls related to biological weapons; it will evaluate the U.S. government’s work with like-minded governments to harmonize regulations to achieve a common goal of stopping the proliferation of biological weapons. Further, the shortcomings of current policy in this area will be examined and recommendations for improvement will be offered. A review of the literature revealed surprisingly little academic research in the area of Biological Export Control regimes, and their effectiveness from a policy standpoint. This review seeks to add to and broaden the policy discussion in this important area.

Economic Analysis of the Market for Weapons Proliferation

Proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD) occurs because there is a market for them. In their publication Arms Export Controls and Proliferation [1], Levine and Smith point out that the arms trade exists at the intersection of foreign policy and economic concerns. Actors in this market consider factors such as security and international order alongside factors like profit, trade and jobs. In 2000, the arms trade market was estimated to be $30 billion. When this market is left unchecked, arms races inevitably flourish. Arms buyers have a utility function measured by their security which is a function of their own stock of arms compared with those of rival countries or other antagonists.

Countries can increase their security by increasing military capability, but as they do so, the security of their rival decreases, forcing them to attempt matching or exceeding their adversary’s strength. Therefore security has a negative externality that makes an arms race more likely. Based on the economic framework detailed in this analysis, arms are a “bad,” therefore restricting supply is warranted. Suppliers in this market have options to restrict supply, one of which is to jointly regulate arms exports. In fact, in this model “… the optimal market structure for the arms industry could be a cartel of cooperating producer countries [1].” In other words, treaties and arms control regimes are a good solution, allowing producers to act as a joint monopoly, driving up prices and reducing quantity. There is, however, a drawback to this approach, which is that when suppliers drive up prices and reduce quantity, buyers will be driven towards acquiring the capability to produce weapons domestically, or acquire them by some other means, thereby increasing the likelihood of non-cartel actors participating.

Another important factor is the worldwide proliferation of the biotechnology industry. In a Biodefense Net Assessment released in early 2012 [2], Robert Carson details the important economic factors leading to increased demand for biotechnology infrastructure in numerous countries including Pakistan, India, and China. This is a key concern because diverting existing biotechnology infrastructure towards nefarious purposes is easier than establishing the infrastructure in the first place. As the biotechnology industry proliferates for peaceful purposes, it will become more difficult for analysts to track these capabilities across the globe.

It is for these reasons that an effective export control regime should be associated with concurrent measures to prevent the spread of key technologies to potential producers. With this economic framework in mind, a biological arms race in which the state parties have agreed to the cartel theory with no production is considered and analyzed.

Background on American Participation in Biological Arms Control

The Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production and Stockpiling of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxin Weapons and on Their Destruction, also known as the Biological Weapons Convention (BWC), is the key treaty binding the United States to its position in opposition to the proliferation of biological weapons. Member nations agree:

“never in any circumstances to develop, produce, stockpile or otherwise acquire or retain:

(1) Microbial or other biological agents, or toxins whatever their origin or method of production, of types and in quantities that have no justification for prophylactic, protective or other peaceful purposes;

(2) Weapons, equipment or means of delivery designed to use such agents or toxins for hostile purposes or in armed conflict [3].”

Further, Article III of the BWC, which came into force in 1975, states that:

“Each State Party to this Convention undertakes not to transfer to any recipient whatsoever, directly or indirectly, and not in any way to assist, encourage, or induce any State, group of States, or international organizations to manufacture or otherwise acquire any of the agents, toxins, equipment or means of delivery specified in Article I of this convention [3].”

The intent of the language is clear. States Parties are seeking to eliminate the spread of biological weapons. However, Article X of the BWC suggests that developed nations assist developing nations in establishing scientific and research infrastructure for peaceful purposes. This illustrates the difficult position producer nations find themselves in when navigating these regulations. On one hand we seek to control the proliferation of dual use technologies, and on the other hand we seek to help developing nations build infrastructure for peaceful purposes.

The development of a biological agent capable of causing harm, or at least capable of inciting terror on a significant scale, requires little more than some rudimentary laboratory skills and access to highly infectious biological material. Developing and delivering an actual biological weapon in a battlefield setting would be a considerable feat, but carrying out an attack in a public setting would be much easier and has been done (albeit with limited success) on a number of occasions [4]. State-level infrastructure (large power sources, capital equipment, and large numbers of highly skilled personnel) is not required to accomplish a small scale attack on innocent civilians. An actor intent on developing such a capability would need to acquire a few key pieces of equipment, a suitable pathogen, and perhaps some technology in the form of specific information related to the handling, growth and dissemination of their agent. It’s fair to say that a treaty so broadly written as the BWC is not, by itself, adequate insurance against preventing an actor intent on acquiring these materials from gaining access on an international level. Far more detailed regulations, implemented by numerous key supplier countries are required to ensure that manufacturers, exporters, and shippers are not permitted to make those materials available to potential adversaries. In the case of biological weapons materials, such regulations do exist and they are based on the collaborative recommendations of a group founded to address this very issue, The Australia Group (AG).

The Australia Group (AG) provides the basis for a specific export control regime. The group defines itself as an “informal forum of countries which, through the harmonization of export controls, seeks to ensure that exports do not contribute to the development of chemical or biological weapons [5].” The Australia Group’s work directly supports the BWC. The BWC has been criticized due to the lack of a robust verification mechanism, but the AG’s work constitutes an important continuing movement towards solving this important problem. The AG does not seek to limit biological or chemical trade or cooperation that is not related to chemical and biological weapons activities or terrorism. This is an important consideration because many of the technologies on the group’s Common Control List, or list of controlled dual-use technologies, have utility in a number of medical and research settings related to the very important fields of public health and medicine. Furthermore, many of these technologies are used for the development of chemical and biological defense efforts of the United States Government as well as governments of other States party to the BWC. Banning them entirely makes little sense.

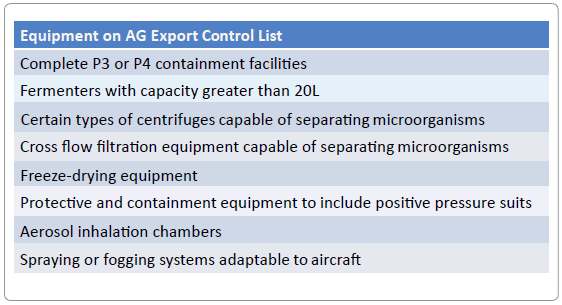

Appreciation for the technologies controlled by this regime can be gained by reviewing the Australia Group’s Common Control List [6] which includes the following types of Equipment:

Also included on the control list are 39 viral pathogens, 17 bacterial pathogens, 19 toxins, and 2 fungi. There are also restrictions on related technology, and certain types of computer software, as they each pertain to biological agents or dual use biological equipment. The Australia Group recommends that member countries require export licenses on all items on their Common Control Lists. In addition, specific regulatory guidelines must be followed when member countries are considering the potential transfer of these materials and equipment.

Membership and Participation in the Australia Group

The Australia Group currently has 41 members, far fewer than the 165 signatories to the BWC. To become a member in the AG a country must be a manufacturer, exporter, or trans-shipper of AG controlled items. This limits membership to only those countries in a position to regulate exports. The process of becoming a member is fairly straight forward [7]. An interested country may submit a letter to the AG Chair, who will then begin the process of seeking advice from AG members. This will be followed by discussion at the AG plenary meeting taking place the year following the country’s application. The AG Chair will meet with the interested country to ensure that it meets all the requirements for membership, and review the country’s policy and legislation regulating export controls. Member countries have the opportunity to raise any concerns they may have with the applicant. Once this process is complete a unanimous vote is required to admit the applicant.

Eighteen countries formed the AG in 1985, and since then countries have steadily been added, although no new members have been admitted since 2005. Key founding members are the United States, The United Kingdom, France, Germany, Canada, and Australia. Several states from the former Soviet Union have joined including Ukraine, Lithuania, and Estonia. Notably absent from membership are Russia, China, and India, all of which are signatories to the BWC and all of which produce and export items on the AG control lists. One possible reason that some key countries may not seek membership in the AG may be found in the membership criteria, which states, in part, that member countries must create “relevant channels for the exchange of information including: accepting the confidentiality of the information exchange; creating liaison channels for expert discussions; and creating a denial notification system protecting commercial confidentiality [7].” This is effectively an intelligence sharing provision, which could be considered intrusive to regimes not wanting outside parties to have access to their intelligence apparatus.

For the sake of developing more inclusive, more effective export control policy, further discussion of the countries notably absent from AG membership is warranted. In 2003 the CIA published an Unclassified Report to Congress in which it noted that:

“Iran continued to vigorously pursue indigenous programs to produce WMD-nuclear, chemical, and biological-and their delivery systems as well as ACW [Advanced Conventional Weapons]. To this end, Iran continued to seek foreign materials, training, equipment, and know-how. During the reporting period, Iran still focused particularly on entities in Russia, China, North Korea, and Europe [8].”

From this report it seems clear that states seeking WMD, most notably Iran, viewed Russia and China as potential sources of restricted materials. Therefore, understanding why these countries, and other major exporters such as India, are not participating in the predominant biological export control regime would benefit policy makers attempting to strengthen these regulations.

In 1997 China declined an invitation to join the AG. The official Chinese position is that the AG’s trade restrictions are too harsh, discriminatory, and not compatible with the Chemical Weapons convention [9]. Interestingly, and despite their official position, China has updated its export control regulations to include restrictions on all major items on AG control lists. According to the State Department, the United States still sees “…proliferation activity by some Chinese entities, however, which has resulted in sanctions against these, companies [10].” There is, therefore some nuance to the Chinese position opposed to membership in the AG, but in favor of implementing similar export controls.

India, for their part, had several entities sanctioned by the George W. Bush administration for transferring technologies and knowhow to Iraq that could contribute to chemical or biological weapons programs [11]. Considering that India is a major manufacturer of chemicals and drug products, and considering that India has a robust biological defense program, its proliferation record is a serious concern. According to David Albright of the Institute for Science and International security, India’s export control system is poorly run, and therefore it will remain a target for States seeking to develop biological weapons [12].

Implementation of the AG’s Export Control Regime in the United States

In the United States responsibility for implementation of these export controls is left to a number of federal agencies. Leading the pack is the Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS). The implementation policies are outlined in the 2006 Foreign Policy Report, Chapter 7 [13], and explicitly support Australia Group objectives and the BWC. Generally, compliance with the norms established by the Australia Group the Department of Commerce requires a license to export certain human pathogens, genetically modified microorganisms, and the technology for their production. Surprisingly, these regulations do not prohibit exporting these commodities to recipients they know will use them to develop or stockpile biological weapons; the exporter need only apply for a license to do so. It is up to the Department of Commerce to deny the license application when it determines that the export in question will be used for nefarious purposes.

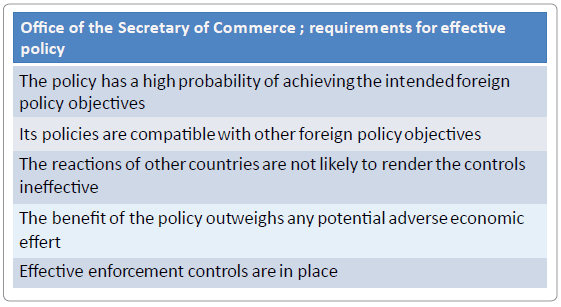

As the controlling authority for these matters, the Office of the Secretary of Commerce performs an analysis of these control regimes to ensure that the United States is implementing a meaningful policy, consistent with objectives. This analysis is complex. The Secretary must ensure the following [13]:

The Secretary of Commerce approves a license when it is determined that these standards have been met, with the caveat that this control regime alone is not sufficient to achieving the very broad overarching goal, stated in the Geneva Protocol of 1925, eliminating the use of biological weapons. It is important to note, however, that this list does not include the development of specific, measurable outcomes that can be empirically shown to result in a desired policy outcome. This is, of course, very difficult to do in such a complex environment, especially considering the explosion in the global biotechnology industries. Nevertheless, it will be essential to ultimately determine the effectiveness of these policies.

Structure of America’s Export Control Regulations

To further evaluate the effectiveness of America’s export control regime it is useful to examine the structural elements of the program itself, and the administration of the program within the federal bureaucracy. This is the area where abstract policy goals meet concrete enforcement techniques. By examining the structure of the bureaucracy, the authorities of the various regulators, and their ability to prevent dangerous materials from getting into the wrong hands, we can gain a better understanding of the prospects for long-term success.

Export control enforcement falls mainly to the Department of Commerce and the Department of State. Department of Commerce regulates export of dual-use items, while the Department of State regulates the trade of actual armaments. Occasionally these lines are blurred, especially with regard to biological materials. Within the Department of Commerce, the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) oversees dual-use export control regulations. These regulations are contained in 15 Code of Federal Regulations, Chapter 7, and the Export Administration Regulation [14]. This regulation lapsed in 2001, and since then Presidents have relied on Executive Order 12924, which is effectively an extension of the Export Administration Act. The authority to do this is based on invocation of emergency powers under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act [15]. It is unclear why the Export Administration Regulation has not been established as a permanent regulation.

Three offices within the Bureau of Industry and Security take the lead in export control activities: the Office of Export Enforcement (OEE), the Office of Enforcement Analysis (OEA), and the Office of Anti boycott Compliance. Their stated mission is in line with the goal of the Australia Group which is to ensure that exports do not contribute to the development of biological weapons. These offices combine to form an “elite law enforcement organization [16].” This paper will only look at the OEE and the OEA.

The Office of Export Enforcement (OEE) works to keep items on control lists out of the hands of potential terrorist organizations. OEE Special Agents have the authority to make arrests, execute search warrants, serve subpoenas, and detain and seize goods about to be illegally exported. One major activity conducted by OEE Special Agents is called an “end-use check.” It is part of the OEE’s Sentinel Program. Trained Special Agents travel to importer countries to visit end-users of controlled commodities to determine if the products are being used in accordance with license conditions and the Export Administration Regulation. In other words they work to ensure that dual use technologies are not used to produce biological weapons.

Also within BIS is the Office of Enforcement Analysis (OEA), focused on ensuring that export transactions are in compliance with the Export Administration Act. Mainly an administrative organization, OEA screens license applications and tracks end-users in an attempt to confirm compliance with regulations on the use of imported dual use material. OEA stations some Special Agents overseas at key embassies to ensure that dual use goods in their region are used in accordance with export control laws and regulations. OEA also retrospectively analyzes Shippers Export Declarations to identify those that may have violated statutes within the Export Administration Regulation. These cases are referred to OEE for investigation by Special Agents. OEA also reviews visa applications to prevent unauthorized access to controlled technology or information by foreign nationals visiting the United States. The OEA keeps lists of persons and entities that are restricted or prohibited from trading with persons and entities within the United States.

Within the Department of State, authority to regulate arms exports is derived from Section 38 of the Arms Export Control Act (22 U.S.C. 2778) which authorizes the President to control the imports and exports of defense related items and technologies [17]. The specific authority to enact export control regulations was delegated to the Secretary of State in Executive Order 11958. The Secretary of State in turn designated authority to the Deputy Assistant Secretary for Defense Trade Controls and the Managing Director of Defense Trade Controls, the latter working within the Bureau of Political Military Affairs.

Like the Department of Commerce, the Department of State maintains a control list called the United States Munitions List [18], Part 121 of the International Trade in Arms Regulation (ITAR). While the Department of Commerce’s Common Control List contains numerous specific viral and bacteriological threat agents, the Department of State’s United States Munitions List is far more general, as seen in Category XIV of the United States Munitions List, Toxicological Agents, Including Chemical Agents, Biological Agents, and Associated Equipment. Although this list contains numerous specific chemical agents, the only mention of biological agents comes in Paragraph (b) which regulates:

“Biological Agents and biologically derived substances specifically developed, configured, adapted, or modified for the purpose of increasing their capability to produce casualties in humans or livestock, degrade equipment or damage crops [18].”

Interestingly, this Paragraph (h) also regulates access to medical countermeasures to treat diseases caused by biological weapons, along with relevant types of equipment. It not only restricts access to biological materials, but in medical countermeasures able to treat those infected with such materials. This is logical when considering that it would be easier to work with potential threat agents if accidentally exposed workers could be treated. This restriction would in theory make it more difficult to develop biological weapons, and therefore contributes to the overall nonproliferation goal.

With two major regulators in the arena of biological export controls, both operating from different lists of controlled substances, equipment and technologies, and each with different levels of specificity, the resulting confusion concerning applicable statutes and agency jurisdiction is understandable. This is a key issue and will be discussed at more length in the following sections.

Measuring the Effectiveness of Export Controls

In terms of measuring the effectiveness of this export control regime there are several key resources we can examine. First, in a 1992 report to then Senator Al Gore [19], The United States General Accounting Office (GAO) stated that the Biological Weapons Convention itself “…has not been effective in stopping the development of biological weapons.” Key among the GAO findings was the fact that in 1972 when the BWC was opened for signature, four countries were suspected of developing biological weapons, and by the time the report was written in 1992, that number had risen to 10 and some of the 10 were actually signatories to the BWC. The report acknowledged the establishment of the Australia Group’s export control regime, but noted that it could not be effective unless the group’s membership was expanded. Since the 1992 GAO report was published, the Australia Group membership has grown from an initial membership of 15 to the current 41. The GAO predicted that:

“The ultimate effectiveness of export controls will be limited because the nature of biological agents makes it difficult to enforce such controls. They are most effective when complemented by other international agreements such as the Biological Weapons Convention. However, for the Convention to be effective, some form of verification regime may be needed [19].

GAO also noted that coordination and education efforts surrounding licensing requirements would be needed to strengthen these regimes. This effort has had some success when measured by the number of export license applications received. During the six-month period from March to August 1991, only 2 licenses for equipment were applied for. Further, for the six weeks following imposition of export controls, The Department of Commerce reported no license applications for toxins. Contrast that with the 2006 report from Commerce showing that in fiscal year 2005, 1,333 license applications valued at $39M were approved for the export of biological agents and equipment, the vast majority of which were for toxins. Three applications were denied, and 24 more were returned without action. The primary reason for return was insufficient information about the transaction [20]. Clearly, some improvement has been made in strengthening these regimes. But is it enough?

Measuring the effectiveness of an export control regime is very difficult, and requires a full understanding of the goals of the export regime itself. The Australia Group seeks to ensure that “…exports do not contribute to the development of chemical or biological weapons [5].” The goal of the specific export control regime is not to stop the development of biological or chemical weapons, or even to stop their proliferation. Those are broader goals expressed in the BWC. Export control regulations derived from the AG seek only to ensure that exports do not contribute to proliferation, and they are only one tool used to achieve the goals of the broader treaties.

Another GAO report entitled “Fundamental Reexamination of System Is Needed to Help Protect Critical Technologies” [21] provides more insight into the U.S. government’s view on the effectiveness of export control regimes. Based on the testimony of Anne-Marie Lasowski, GAO’s Director of Acquisition and Sourcing Management, there are a number of flaws in the programs we rely on to protect critical technologies. Several of these flaws stem from a complex, cumbersome bureaucracy administered by multiple federal agencies, each responsible for regulating different technologies. The Dual-Use Export Control System is administered by seven different federal agencies: the Department of Commerce (lead), Department of State, Central Intelligence Agency, Department of Defense, Department of Energy, Department of Homeland Security, and Department of Justice. “Each agency represents various interests, which at times can be competing and even divergent [21].”

The two Departments regulating the most in this arena, Commerce and State, suffer from poor communication and coordination, and have significant backlogs of license applications. Further, they often disagree on which materials and technologies are controlled by which agency. These jurisdictional disputes were specifically identified in the GAO’s testimony before Congress. Because the State Department regulates arms, and Commerce regulates dual-use items, Commerce’s controls tend to be less restrictive than State’s. Therefore, the GAO argues, determining who has jurisdiction over different items is key to ensuring the effectiveness of these regulations. Jurisdictional disagreements are based on differing interpretations of the underlying regulations, but are exacerbated by poor communication and coordination. GAO concludes in this testimony that these shortcomings increase the risk that restricted items will be exported without proper oversight [21].

Despite the difficulties with measuring the effectiveness of export control regimes, some available data may help provide insight. The number of export violations prosecuted by the Bureau of Industry and Security can be evaluated to gain insight into how the volume of violations changes over time. While this is not a true measure of the overall effectiveness of the regulations, when coupled with the increase in license applications cited above, it does show the degree to which American exporters are complying with regulations. Based on data provided by BIS, listing prosecuted export violations from January 2006 to the present, we can track the number of cases over a nearly six year period [22]. According to this data, the number of prosecuted export violations dropped from 93 in 2006 to 46 in 2011, a 50% decrease. It is not known whether this is the result of a better informed producer base avoiding inadvertent violations, or simply the result of a decreased number of transactions involving sensitive materials. A full evaluation of the effectiveness of these policies is an area for future research.

Conclusions

Harmonizing biological export controls at the national and international levels is a significant challenge, but vital for reducing the risk of attack with a biological agent. Our primary recommendation, and probably the easiest to achieve is for all federal agencies to come to some agreement on what specific items fall under each one’s jurisdiction. And because each agency’s regulatory bodies are likely to encounter items falling under another’s jurisdiction, some communication mechanism must be established for easy referral between them.

At the international level, several key countries do not participate in the Australia Group, and therefore the ability of the group to ensure that exports are not contributing to the proliferation of biological weapons is really in question. Therefore a recommendation for federal policy makers is to devise national and international measures of effectiveness, again, at strategic, operational and tactical levels. Establishing the BWC and the Australia Group were important first steps taken to reduce the hazard of biological weapons. It is time now to continue the very difficult process of policy evaluation in this area. It is important to know how the Australia Group’s collective biodefense posture is affecting the motivation of countries to proliferate dual-use technologies.

At the national level, a full review of the effectiveness of export control policies has not been done, and therefore it is unclear if current policies are having the desired effect of ensuring that exports are not contributing to the proliferation of biological weapons. We recommend that the Departments of Commerce and State differentiate between the strategic, operational and tactical policy goals of their regulations. Our research did not uncover a statement from these departments that drew a clear line between specific regulations and the broader policy goals they hoped to achieve. Without this, outside policy analysts will be unable to determine if a desired end state is being met. For example, at a tactical level, do export licensing requirements result in less proliferation of dual-use technologies? If so, by how much? From an operational perspective, has a reduction in the proliferation of dualuse technologies resulted in fewer state actors with the infrastructure capable of being used for nefarious purposes? Finally, from a strategic standpoint, has there been any reduction in the number of states believed to be pursuing biological weapons?

In support of Article III of the BWC the US Government has made a concerted effort to establish regulations intended to stem the proliferation of biological weapons technology. The effort is substantial and justifiably requires a multi-agency approach. As the lead agency for the Executive Branch, Commerce bears the responsibility for the coordination of this effort. Understanding the multiple facets of export control (domestic vs. international, state vs. non-state actors) requires communication and coordination among the many Departments that have a stake in the effort. Commerce cannot undertake the effort on its own and because each agency’s regulatory bodies are likely to encounter items falling under another’s jurisdiction, some communication mechanism must be established for easy referral between them.

Commerce’s role should be focused on the domestic side of the equation but receiving input from State and others on how those domestic decisions impact the role of the US internationally. This will require Commerce to be the single agency administering the Dual-Use Export Control System with all other agencies providing some means of support.

The State Department should focus its efforts on encouraging other nation states to equitably enforce the regulations they have enacted or participate on equal footing with the larger world community to explicitly support the BWC. This effort begins with additional encouragement for non-participatory nations to join The Australia Group.

These recommendations will result in a more managable export control system that can be analyzed more rigorously. In the end the stakeholder community will have more confidence that the system is aiding efforts to meet national and international non-proliferation goals.

Acknowledgements

The views expressed in herein are those of the authors only, and do not represent an official position of the Transformational Medical Technologies program, the Joint Program Executive Office for Chemical and Biological Defense, or the United States Army.

The author’s thank COL Jonathan Newmark for helpful discussion and Theresa Brady for editorial input.

Portions of this review were originally conducted at George Mason University School of Public Policy as part of a final research project for the class WMD Arms Control Policy (Professor Wayne D. Perry, Fall Semester 2011).

References

- Levine P, Smith R (2000) Arms Export Controls and Proliferation. J Conflict Resolut 44: 885-895.

- Carlson R (2012) Causes and Consequences of Bioeconomic Proliferation: Implications for U.S. Physical and Economic Security. Biodefense Net Assessment.

- (1972) Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production and Stockpiling of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxin Weapons and on Their Destruction.

- Carus SW (2002) Bioterrorism and Biocrimes: The illicit Use of Biological Agents since 1900. Fredonia Books, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

- https://www.australiagroup.net/en/index.html

- https://www.australiagroup.net/en/dual_biological.html

- Australia Group Membership.

- Central Intelligence Agency, Unclassified Report to Congress (January- June 2003) Attachment A, Unclassified Report to Congress on the Acquisition of Technology Relating to Weapons of Mass Destruction and Advanced Conventional Munitions.

- (2004) Nuclear Threat Initiative. China and Multilateral Export Control Regimes.

- (2012) Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs.

- Arms Control and Proliferation Profile: India.

- Albright D, Basu S (2006) Neither a Determined Proliferator Nor a Responsible Nuclear State: India’s Record Needs Scrutiny. Institute for Science and International Security (ISIS).

- (2006) Foreign Policy Report. Bureau of Industry and Security United States Department of Commerce.

- Policies and Regulations. Bureau of Industry and Security United States Department of Commerce.

- Streamlining and Strengthening Export Controls. Bureau of Industry and Security United States Department of Commerce.

- Export Enforcement. Bureau of Industry and Security United States Department of Commerce.

- (2011) International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) Part 120.

- International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) Part 121, The United States Munitions List.

- (1992) Arms Control: U.S. and International Efforts to Ban Biological Weapons. United States General Accounting Office, Report to the Honorable Albert Gore, Jr. United States Senate.

- (2006) Biological Agents and Associated Equipment and Technology. Foreign Policy Report, Bureau of Industry and SecurityUnited States Department of Commerce.

- (2009) Export Controls. Fundamental Reexamination of System is needed to Help Protect Critical Technologies. United States Government Accountability Office.

- Export Violations. Bureau of Industry and Security Electronic FOIA Reading Room US Department of Commerce.

Relevant Topics

- Anthrax Bioterrorism

- Bio surveilliance

- Biodefense

- Biohazards

- Biological Preparedness

- Biological Warfare

- Biological weapons

- Biorisk

- Bioterrorism

- Bioterrorism Agents

- Biothreat Agents

- Disease surveillance

- Emerging infectious disease

- Epidemiology of Breast Cancer

- Information Security

- Mass Prophylaxis

- Nuclear Terrorism

- Probabilistic risk assessment

- United States biological defense program

- Vaccines

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 13889

- [From(publication date):

September-2012 - Nov 12, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 9229

- PDF downloads : 4660