Research Article Open Access

Treatment of Breast Cancer in Women Aged 80 and Older: A Systematic Review

Sarah Blair*, Julie Robles, Anna Weiss, Erin Ward and Jonathan UnkartUniversity of California San Diego Health System La Jolla, CA, USA

- *Corresponding Author:

- Sarah Blair

University of California San Diego Health System La Jolla

CA, USA

Tel: (858) 822-1230

E-mail: slblair@ucsd.edu

Received date: October 10, 2016; Accepted date: November 07, 2016; Published date: November 12, 2016

Citation: Blair S, Robles J, Weiss A, Ward E, Unkart J (2016) Treatment of Breast Cancer in Women Aged 80 and Older: A Systematic Review. Breast Can Curr Res 1:115. doi:10.4172/2572-4118.1000115

Copyright: © 2016 Blair S, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Breast Cancer: Current Research

Abstract

Background: The elderly population is growing in the United States. Most clinical trials exclude patients over 80, therefore there is a paucity of data regarding the correct treatment of this group. The purpose of this systematic review was to investigate the treatment patterns for women with primary breast cancer aged 80 years old and older - modalities include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation and hormonal treatment, alone or in combination.

Methods: A formal systematic review was performed with the support of the medical research librarian at the University of California San Diego Biomedical Library. PubMed and Web of Science were the databases used. A patient population of 2,947 was derived from the 16 papers reviewed.

Results: Patients diagnosed over 80 were more likely to be diagnosed by clinical exam. Patients who had standard surgical treatment had an improved disease free survival. Surgical resection and radiation had a low morbidity.

Conclusion: Multimodality treatment is safe in elderly women and is associated with better breast cancer specific survival outcomes.

Keywords

Breast cancer; Elderly breast cancer; Elderly cancer treatments; 80 years and older; Oncologic surgery in the elders

Introduction

According to the latest United States census, there are 16.7 million Americans aged 80 and older, and 65% of these seniors are women [1]. The elderly are the fastest growing segment of the population, and the risk of cancer greatly increases with age. In the US, cancer is the second most common cause of death in women aged 75 years and older [2]. The risk of breast cancer nearly triples for women aged 70 to 80 to a rate of 43 in 1000 women, compared to 15 in 1000 women aged 40-50 [2].

There is no agreed upon standard of care for elderly women with breast cancer. In addition, the screening guidelines for yearly mammograms are vague and contradictory [2-6]. The decision for elderly women to continue breast cancer screening is a controversial issue, [7] and the pursuit of treatment for newly discovered breast cancer is an equally complex decision that is lacking in data. Factors that influence treatment patterns are difficult to measure and report. Though patients apply their own psychosocial factors, physician recommendation was the most influential factor in treatment decision [8]. Given the heterogeneity of the population, providers may not recommend treatment, even though there is evidence that octogenarian women with breast cancer die from their disease as often as younger women [9]. Furthermore, evidence shows that older women tend to face the same as younger women with comparable treatment [10,11].

Patients over 65, and especially over 80, are underrepresented in clinical trials and are either overtly excluded or not enrolled [12-14]. The National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project studies, for example B-18 and B-32, [15,16] compare treatments in patients younger or older than 50 years of age. Hutchins et al. [17] examined the underrepresentation of patients over 65 years of age in cancertreatment trials, and found that only 9% of breast patients enrolled in clinical trials are over 65. In a trial by Muss et al. [18], which specifically studied the use of chemotherapy in the elderly (over 65), only 4.4% of the patient cohort was over 80. Furthermore, it could be argued that a 65-year cohort is not elderly anymore, as our population continues to age and life expectancy rises. Little to no research exists for the oldest of old, specifically octogenarians. The goal of this review is to investigate the treatment patterns used for women with primary breast cancer aged 80 years old and older-modalities include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation and hormonal treatment, alone or in combination-and their survival.

Methods

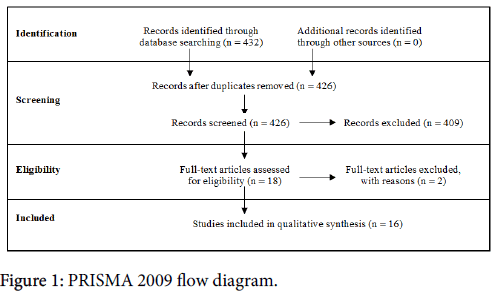

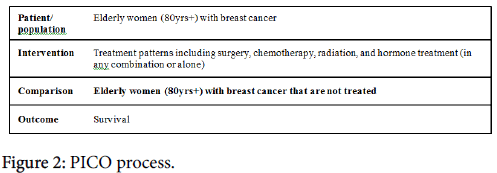

A formal systematic review was performed with the support of the medical research librarian at the University of California San Diego Biomedical Library. PubMed and Web of Science were the databases used and a search was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) Statement, issued 2009 (Figure 1). PICO was used to build the search criteria (Figure 2). The PRISMA Group worked to revise prior reviews and meta-analyses guidelines that had been established called QUOROM (Quality of Reporting of Meta-analyses), and released the PRISMA statement [19]. The goal of these groups was to address poor quality reviews and reporting of randomized data in the format of metaanalyses. The principle is simple – researchers can follow the PRISMA guidelines to develop high quality research questions, capture the relevant studies, and critically appraise the relevant studies. The PRISMA guidelines include a 27-point checklist, and a four-phase flow diagram that guides researchers through the review process.

An updated search on PubMed and Web of Science was conducted using MeSH terms (Medical Subject Headings) in PubMed, and keywords in both PubMed and Web of Science. The search terms used include the following: "Breast Neoplasms"[MeSH] OR "Breast Neoplasms" AND "elderly"; then keywords “treatment”, “surgery”, “chemotherapy”, “hormone therapy” and the associated MeSH term for each treatment modality. Lastly “survival” or “recurrence” search terms were added, AND NOT "metastatic" NOT "advanced”; filter: “aged 80 and over” was applied. Eligible literature included randomized trials and retrospective studies on the treatment of elderly women. The papers had to be written in English, full-text peer-reviewed, and published after 1/1/1997.

The year 1997 was chosen because this is the year that anastrazole was approved, thus including publications that would have modern era hormonal treatments available. Selection criteria included primary breast cancer, early stage breast cancer, and patients 80 years old and older. Case reports, reviews, book chapters, patients with metastases, and patients with inflammatory cancer were excluded.

The literature review was performed in July of 2015. 432 papers were identified by JR. After duplicates were removed, 426 papers were screened using the abstracts in parallel by JR and AW. Early on during abstract review, it was recognized that there were very few papers that reported specifically on the over 80 population and early stage breast cancer. Thus the inclusion criteria was expanded to include all stages of breast cancer, except metastatic. 18 papers fit the above inclusion criteria and were selected to undergo full-text review. Every manuscript and patient cohort was closely examined. One study was excluded from the final review [20] because the patient population was identical to a prior study by the same author group [21]. A second manuscript was excluded because it is a SEER based study, which includes all patients in the United States, which inherently overlaps the trials or institutional retrospective patient cohort studies [9].

Two independent reviewers reviewed the remaining 16 papers, and data was separately tabulated [21-36]. Data extracted included number of patients ≥80 years old, stage of disease at time of treatment, tumor characteristics, the different types of treatment plans, and survival (when available). Data integrity and any discordance were settled by consensus between AW and JR. Data was pooled and presented. GRADE analysis was then performed to determine the quality of evidence, and strength of recommendation.

Results

A patient population of 2,947 was derived from the 16 papers reviewed. A summary of the papers reviewed is shown in Tables 1-3. At time of treatment, 93 (3.2%) women had non-invasive disease, 1,736 (58.9%) women had early stage breast cancer (stage 1 or stage 2), 527 (17.9%) women had late stage breast cancer (stage 3 or stage 4), and 169 (5.7%) women had an unknown or unreported stage of disease. Table 4 shows stage, tumor size and hormone status when reported. See Supplemental Table 1 for the complete list and summary of the papers reviewed. The significant heterogeneity of treatments provided and outcomes studied is displayed.

| Paper | Year | Median follow-up | # of pts | Treatment | Overall survival | Breast cancer specific survival | Study design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mery et al. [18] | 2014 | 39 weeks | 44 | Radiation | 88% | NR | Retrospective cohort study |

| Bouchardy et al. [15] | 2003 | 5 years | 48 | None | 5-yr: 11% | 5-yr: 46% | Retrospective cohort study |

| 132 | Hormone tx | 5-yr: 18% | 5-yr: 51% | ||||

| 28 | BCS alone | 5-yr: 27% | 5-yr: 63% | ||||

| 55 | Mastectomy | 5-yr: 52% | 5-yr: 82% | ||||

| 78 | Mastectomy +adjuvant tx | 5-yr: 44% | 5-yr: 62% | ||||

| 57 | BCS +adjuvant tx | 5-yr: 67% | 5-yr: 91% | ||||

| 9 | Misc | 5-yr: 22% | 5-yr: 42% | ||||

| Cortadellas et al. [16] | 2013 | 65 months | 30 | Unspecified surgery + chemo | NR | Early stage cancer: 108mos(95%CI 101-115); Late stage cancer: 76mos (95% CI 62-89) |

Retrospective cohort study |

| 42 | Unspecified surgery + radiation | ||||||

| 140 | Unspecified surgery + hormone tx | ||||||

| 58 | Hormone tx | Early stage cancer: 50mos (95%CI 39-61) Late stage cancer: 68mos (95% CI 49-86) |

|||||

| 10 | Chemo + hormone tx | ||||||

| 16 | Radiation + hormone tx | ||||||

| Dialla et al. [19] | 2012 | 3 years | 15 | None | 1-yr RS: 93.5% (95%CI 91-96)* 5-yr RS: 78.2% (95%CI 72-83)* |

NR | Retrospective cohort study |

| 33 | Unspecified surgery alone | ||||||

| 62 | Hormone tx | ||||||

| 94 | BCS + unspecified adjuvant tx | ||||||

| 119 | Mastectomy + unspecified adjuvant tx | ||||||

| 8 | Other |

Table 1: Studies that included nonsurgical treatment arms. *Relative Survival. These numbers were not stratified by age group or treatment type. NR=Not reported, TX=Treatment, BCS=Breast Conserving Surgery.

| Paper | Year | Median follow-up | # of pts | Surgical tx | Adjuvant tx | Overall survival | Disease free survival | Study design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Litvak et al. [13] | 2006 | NR | 103 | Mastectomy, BCS | Radiation, hormone tx, chemotherapy | NR | NR | Prospective database |

| Morishita et al. [32] | 1997 | NR | 39 | Mastectomy, BCS | Radiation, hormone tx, chemotherapy | 10-yrs: 78% | 77% | Retrospective cohort study |

| Strader et al. [31] | 2014 | NR | 50 | Mastectomy, BCS | Radiation, hormone tx | NR | NR | Retrospective cohort study |

Table 2: Surgical treatment excluding the axilla. NR=Not Reported, TX=Treatment, Mast=Mastectomy, BCS=Breast Conserving Surgery.

| Paper | Year | Median follow-up | # of pts | Surgical tx | Adjuvant tx | Overall survival | Disease free survival | Breast cancer specific survival | Study design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angarita et al. [14] | 2015 | 14 months | 217 | Mastectomy, BCS, SLNB, ALND | Radiation, hormone tx, chemotherapy | ≥80: 53mos | ≥80: 17.5mos | NR | Retrospective cohort study |

| Besic et al. [21] | 2014 | 5.3 years | 154 | Mastectomy, BCS, SLNB, ALND | Radiation, hormone tx, chemotherapy | NR | NR | 5-yr: 83% | Retrospective cohort study |

| Chatzidaki et al. [25] | 2011 | NR | 129 | Mastectomy, BCS, ALND | NR | NR | NR | Retrospective cohort study | |

| Cyr et al. [22] | 2011 | 34 months | 134 | Mastectomy, SLNB, ALND | Radiation, hormone tx, chemotherapy | 65% | NR | NR | Retrospective cohort study |

| Evron et al. [17] | 2006 | 70 months | 135 | Mastectomy, BCS ALND | Radiation, hormone tx, chemotherapy | 75% | Median: 22mos | 91% | Retrospective cohort study |

| Guth et al. [20] | 2013 | 13 months | 79 | Mastectomy, BCS, SLNB, ALND | Radiation, hormone tx, chemotherapy | NR | NR | NR | Prospective database |

| Joerger et al. [12] | 2012 | NR | 462 | Mastectomy, BCS, SLNB | Radiation, hormone tx, chemotherapy | NR | NR | NR | Prospective database |

| Rosenkranz et al. [24] | 2006 | 4 years | 213 | Mastectomy, BCS, SLNB, ALND | Radiation, hormone tx, chemotherapy | Median OS: 7.28yrs | NR | NR | Retrospective cohort study |

| Vetter et al. [23] | 2013 | 14 months | 151 | Mastectomy, BCS, SLNB, ALND | Radiation, hormone tx, chemotherapy | 36% | NR | NR | Prospective database |

Table 3: Multi-modality treatment, surgery in all patients.

| Size | Stage | Receptor expression | ||||||||||||||||||

| Paper | Mean | Median | Range | In situ | Early Stage | Late stage | Unk | ER+ | ER- | ERunk | PR+ | PR- | PR unk | HER2/ neu + | HER2/ neu - | HER2/ neuunk | ||||

| Mery et al. [18] | 4 | 38 | 17 | 1 | 34 | 9 | 1 | 27 | 16 | 1 | 2 | 41 | 1 | |||||||

| Bouchardy et al. [15] | 30mm | 4-130mm | 6 | 254 | 98 | 49 | 88 | 20 | 299 | |||||||||||

| Cortadellas et al. [16] | 189 | 70 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Dialla et al. [19] | 27mm +/- 19.8 | 22mm | 2-160mm | Positive 590, Negative 80, Unknown 11** | ||||||||||||||||

| Litvak et al. [13] | 2cm +/- 2.4 | 5 | 85 | 13 | 43 | 14 | 47 | |||||||||||||

| Morishita et al. [32] | 2.38cm | 2.2cm | 1-7.5cm | |||||||||||||||||

| Strader et al. [31] | 20.1mm +/- 20.2 | 11 | 37 | 38 | 49 | |||||||||||||||

| Angarita et al. [14] | Invasive:2.4cm DCIS: 3cm |

Invasive: 1.7-3cm DCIS: 1.7-4cm |

24 | 184 | 9 | 180 | 37 | 165 | 52 | 31 | 155 | 8* | ||||||||

| Besic et al. [21] | 37mm | 25mm | 5-150mm | 134 | 20 | 90 | 64 | |||||||||||||

| Chatzidaki et al. [25] | 5 | 100 | 23 | 12 | 100 | 16 | 24 | 78 | 36 | 26 | ||||||||||

| Cyr et al. [22] | 16 | 103 | 9 | 94 | 19 | 33 | 11 | 101 | 34 | |||||||||||

| Evron et al. [17] | 121 | 11 | 3 | Positive 102, Negative 21, Unknown 12** | ||||||||||||||||

| Guth et al. [20] | 63 | 16 | All "HR-positive", part of inclusion criteria | 13 | 61 | 5 | ||||||||||||||

| Joerger et al. [12] | 340 | 178 | 104 | 438† | 88†† | 96 | 49 | 256 | 317 | |||||||||||

| Rosenkranz et al. [24] | 22 | 151 | 40 | 132 | 27 | |||||||||||||||

| Vetter et al. [23] | 25mm | 108 | 43 | Positive 94, Negative 27, Unknown 8** | 15 | 10 | 1 | |||||||||||||

Table 4: Tumor Characteristics. Unk = unknown. * HER2/neu equivocal. ** Did not differentiate between ER or PR. † >50% ER expression. †† 65 with <10% ER expression, 23 with 10-50% ER expression.

Four papers included non-surgical treatment strategies alone as a treatment arm, representing 1,078 patients. One paper had radiation alone as the only treatment modality. Two papers had hormone therapy alone, surgery alone, or surgery plus adjuvant treatment as the three treatment arms. Lastly, one paper reported hormone therapy, hormonal and chemotherapy, hormonal and radiation therapy, and surgery plus adjuvant treatments as the treatment arms. One paper reported overall and breast cancer specific survival, two papers reported overall survival only, and one reported breast cancer specific survival only. The longest follow up was 65 months. All studies were retrospective in nature.

Forty-four women (1.5%) underwent radiation as their only form of treatment.

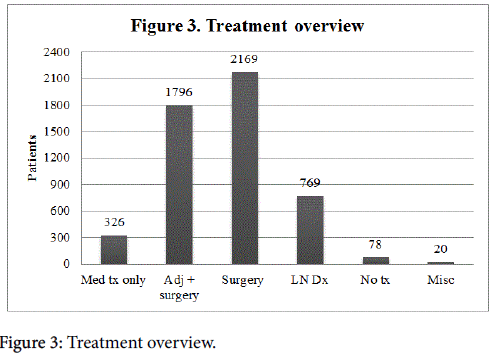

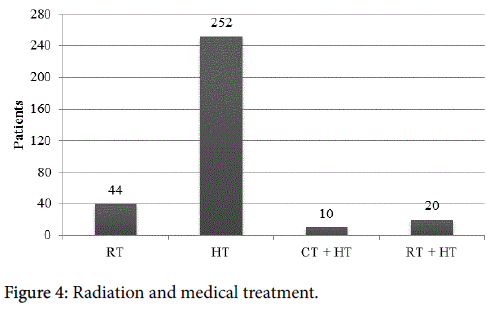

There were multiple treatment modalities, as shown in Figure 3. Three hundred and twenty-six (11.1%) patients received only medical management. Of these women, 252 (77.3%) received hormone treatment, 10 (3.1%) received both chemotherapy and hormone treatment, and 20 (6.1%) underwent radiation and hormone treatment (Figure 4). Seventy-eight (2.6%) women elected for no treatment. Twenty (0.68%) patients were categorized as receiving miscellaneous treatment including 8 that underwent an unspecified combination of chemotherapy, radiation, chemotherapy and hormone treatment, chemotherapy and radiation, radiation and hormone treatment, chemotherapy and radiation and hormone treatment, neo-adjuvant chemotherapy and surgery and adjuvant treatment, neo-adjuvant chemotherapy and surgery; 3 underwent an unknown surgical procedure; and 9 underwent an unspecified treatment.

Three papers included surgical treatment strategies that excluded management of the axilla. This represented 192 patients. All three papers examined mastectomy and breast conserving surgery. Two papers treated with radiation, hormonal, and chemotherapy; one paper treated with hormonal and radiation therapy only. One paper reported both overall and disease free survival; two did not report survival at all. Follow up terms were not reported. One study was a prospectively collected database study; the other two were retrospective studies.

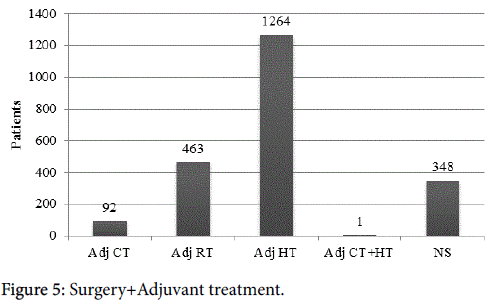

Nine papers included surgical treatment strategies with combinations of adjuvant or neoadjuvant treatments, representing 1,674 patients. All papers included both mastectomy and breast conserving surgery, two papers included axillary node dissection as the only treatment of the axilla, one paper included sentinel node biopsy only, and the remaining six included a combination of the two axillary treatments. All papers included radiation, hormone therapy, and chemotherapy in different combinations. Three papers did not report survival of any kind. One paper reported disease free, breast cancer specific, and overall survivals. Three reported overall survival only, one reported both disease free and overall survival, and one reported breast cancer specific survival only. The range of follow up was 13-70 months, two studies did not report follow up length. Three studies were prospective, and the other six were retrospective in nature. Overall, 2,169 surgical operations were performed (including breast-conserving surgery or mastectomy) with some women undergoing one or more procedures. Seven hundred sixty-nine (35.5%) lymph node dissections were done. Some of these patients (60.9%) underwent some form of adjuvant treatment, often more than one type of therapy. Ninety-two (5.1%) had adjuvant chemotherapy (1 woman in this group was given chemotherapy as neo-adjuvant treatment), in 14 (0.78%) of these women it was unclear whether this was the primary treatment or adjuvant. 463 (25.8%) underwent adjuvant radiation; 1,264 (70.1%) received adjuvant hormone treatment; 1 (0.06%) had both adjuvant chemotherapy and hormone treatment; and 384 (21.4%) underwent an unspecified adjuvant treatment (Figure 5). In general, breast surgery and radiation were associated with low complication rates (37.1%), with few being serious complications (5.7%) [25]. Evron et al. [29] found that women who did not have axillary staging had a higher axillary failure rate, 5.3% versus 0% who underwent axillary staging. Chatzidaki et al. found it would be reasonable to recommend surgery for patients over 80 [25].

Rosenkranz et al. reported that surgical resection was safe in the older age group (0.5% major complications, 5% minor complications) but that intravenous chemotherapy was associated with a higher complication rate (30% major complications) [21].

Overall, the quality of the literature regarding treatment of elderly patients with breast cancer is low quality. Tables 5-7 present the GRADE analysis for each of our clinical questions. The risk of bias is very serious, since all papers are observational or retrospective; there are significant selection and observation biases. This causes the literature to be low quality. The overall treatment recommendation that could be gathered from these studies is weak.

| Outcome | Quality assessment | Summary of findings | Importance | ||||||||||

| No of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Number of patients | Effect | Quality | ||||

| Treated | Untreated | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute (95% CI) | ||||||||||

| Survival | 4 | Retrospective cohort study, prospective database | Serious* | ** | Not serious | Not serious | None | 1018/1037 | 107/1037 | *** | *** | Low | Critical |

Table 5: Studies that included non-surgical treatment arms compared with no treatment for elderly women (80+) with breast cancer. Patients or population: Elderly women (80 yrs+) with breast cancer. Intervention: Medical treatment with or without surgery. Comparison: Elderly women (80 yrs+) with breast cancer that are not treated. *All studies are observational, which carry an inherent risk of bias. **Unable to assess from the data available. ***Unable to be calculated from the data available.

| Outcome | Quality assessment | Summary of findings | Importance | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Number of patients | Effect | Quality | ||||

| Treated | Untreated | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute (95% CI) | ||||||||||

| Survival | 3 | Retrospective cohort study, prospective database | Serious* | ** | Not serious | Not serious | None | 192/192 | NR | *** | *** | Low | Critical |

Table 6: Surgical treatment excluding the axilla compared with no treatment for elderly women (80+) with breast cancer. Patients or population: Elderly women (80 yrs+) with breast cancer. Intervention: Surgical treatment excluding the axilla. Comparison: Elderly women (80 yrs+) with breast cancer that are not treated. NR = not reported. *All studies are observational, which carry an inherent risk of bias. **Unable to assess from the data available. ***Unable to be calculated from the data available.

| Outcome | Quality assessment | Summary of findings | Importance | ||||||||||

| No of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Number of patients | Effect | Quality | ||||

| Treated | Untreated | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute (95% CI) | ||||||||||

| Survival | 9 | Retrospective cohort study, prospective database | Serious* | ** | Not serious | Not serious | None | 1674/1674 | NR | *** | *** | Low | Critical |

Table 7: Multi-modality treatment, surgery in all patients compared with no treatment for elderly women (80+) with breast cancer. Patients or population: Elderly women (80 yrs+) with breast cancer. Intervention: Multi-modality treatment, surgery in all patients. Comparison: Elderly women (80 yrs+) with breast cancer that are not treated. NR = not reported. *All studies are observational, which carry an inherent risk of bias. **Unable to assess from the data available. ***Unable to be calculated from the data available.

Discussion

From this patient population of 2,947, the most common form of treatment was surgery (mastectomy or breast conserving surgery). A total of 2,169 operations were performed, and some women underwent multiple procedures. The most common form of adjuvant treatment was hormonal therapy, which was given to 1,264 (70.1%) women (pre or post-surgical timing of hormonal therapy is not specified in the studies).

The characteristics of primary tumors in elderly women are relatively homogeneous. More than 75% were ER positive, more than 60% were PR positive, and very few were HER2/neu positive (16.2%) [14,18,21,22,24,27,33]. In this population, less than 3% of women refused to undergo treatment of any kind, once their tumor was identified. This seemingly low rate of treatment refusal may not represent the population as a whole, though, since the percentage of octogenarians foregoing mammography is unknown.

There are several limitations of this systematic review, many of which are limitations of the body of literature as a whole. First, this lack of knowledge regarding rates of screening mammograms in octogenarians is a limitation; rates are not reported in any of the studies. The literature highlights that more than half of the tumors in octogenarians were discovered as palpable masses. Once the tumors were identified only 3% refused treatment. However, the rate of octogenarians who sought treatment (97%) may be an overrepresentation since the number of patients that continue to refuse mammograms is never captured. On the other hand, although many patients were not seeking routine screening, when a mass was identified most decided to pursue treatment. This brings to light that perhaps not enough elderly women, who would want treatment, are receiving screening mammograms.

Most of the limitations of this review are due to a wide variety of reporting styles that made the review and classification of our collected data difficult. While most of the papers reported the stage of the patients at time of diagnosis, very few continued the breakdown of treatment modality by stage of disease and some did not report it at all. This presents a unique problem in that survival was reported without adjusting for stage. Specific treatment plans were also reported inconsistently and varied greatly between the papers. Some only reported whether surgery occurred, while others reported the specific surgical intervention (breast-conserving surgery, mastectomy, axillary lymph node dissection, and/or sentinel lymph node biopsy). The reporting of adjuvant treatment also varied, and many reported the specific adjuvant treatment (chemotherapy, radiation, and/or hormone treatment) but not the timing. Other papers reported if the patient was given any adjuvant treatment, without specifying modality (radiation, chemotherapy, hormonal therapy). Some included several study arms in which one cohort received medical treatment only, another cohort received surgery and adjuvant treatment, but these were not compared to each other; instead observations were reported in a retrospective fashion. In a few cases, it was unclear if the medical treatment was the primary treatment or an adjuvant treatment. In summary, the quality of the data is low in all the existing studies regarding treatment of elderly patients with breast cancer.

Despite these weaknesses, this review brings to light several important ideas. Multiple studies show elderly breast cancer patients receive the same survival benefit as younger patients with similar disease [10,11,37-39]. Yet, multiple studies have shown age to be the greatest influence on treatment choice, especially when adjuvant radiation is indicated [20,28,29,31,32,36]. Bouchardy et al. found that less than half of women aged 80 and older received standard treatment [40].

Surgery, including mastectomy, breast-conserving surgery, and axillary dissection, has been shown to have a low complication rate overall and a very low rate of major complications [23,25]. Mery et al. found that 80% of elderly patients were able to complete radiation therapy [33]. In addition, studies by Bouchardy et al., Guth et al., Litvak et al., Van Leeuwen et al., and Vetter et al. showed that both medical and surgical treatment are safe for use in elderly women and multi-modality therapy should not be withheld [20,24,30,32,36]. In the face of these studies touting the safety of multimodality treatment, elderly women with breast cancer continue to receive less treatment than their younger counterparts.

Undertreatment does not uniformly result from ageist beliefs of the physician. Treatment may be discontinued due to recurrence or another serious medical problem unrelated to breast cancer [30]. Undertreatment may also be the result of patient refusal. Noncompliance, especially with adjuvant treatment, is much higher in elderly women than in younger cohorts [35,36]. Vetter et al. found that 13% of elderly patients chose to forgo adjuvant hormone therapy and 49% of elderly patients refused adjuvant radiation [36].

Regardless of the reason, undertreatment is associated with a decreased breast cancer specific survival rate. Bouchardy et al. found 5- year specific breast cancer survival rate dropped from 90% in women receiving breast conserving surgery and adjuvant treatment to 46% in women receiving no treatment [40]. In comparing single modality treatment, women who underwent mastectomy had a much higher 5- year specific breast cancer survival rate at 82% compared to 51% for women receiving only hormonal treatment [24]. Cortadellas et al. have similar results - women who underwent surgery had a mean breast cancer specific survival of 108 months while women who received only medical treatment had a mean breast cancer specific survival of 50 months [26].

Despite an aging population, the relative safety of treatments and the apparent survival benefits of treatment of the elderly, it is difficult to draw firm conclusions from the current body of literature. Although most of the large, randomized-controlled multi-institutional studies exclude the elderly [12-17], CALGB 9343 examined the benefit of radiation following breast-conserving surgery with tamoxifen, in patients over 70 with smaller ER positive tumors [41]. While CALGB 9343 was not included in this systematic review because it studied a slightly younger 70-year-old cohort, it is an important study to discuss. In women with stage 1 estrogen sensitive tumors that took tamoxifen, radiation showed a modest improvement in loco-regional recurrence, but there was no difference in survival. Thus, it is reasonable given this strong level of evidence for elderly patients with favorable histology to forego radiation in this circumstance. It is difficult, though, to expand these types of conclusion to other treatments without evidence. It is necessary to perform more studies like CALGB 9343, and it is the opinion of these authors that clinical trials should begin to include an elder cohort.

Conclusions

Women aged 80 years old and older with breast cancer are most often treated surgically. The majority of these women pursue adjuvant treatment, the most common modality of which is hormone treatment. The overall quality of literature regarding treatment of elderly breast cancer is low, and only weak recommendation to provide standard treatment can be made. Future randomized clinical trials should consider including an elderly cohort to provide better evidence, and guide decision-making in this growing population.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Alexander Ushinsky, MD and Ashley Jameson, BA for their contributions to the manuscript. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest

None

References

- Werner CA (2010) The older population: 2010: 2010 census briefs. U.S. Dept. of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, U.S. Census Bureau. Washington, DC.

- Kimmick GG, Muss HB (2015) Chapter 95. Breast Disease. In: Halter JB, Ouslander JG, Tinetti ME, Studenski S, High KP, Asthana S. eds. Hazzard's Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology, 6e. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- ACOG (2015) Practice Advisory on Breast Cancer Screening. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Accessed.

- Oeffinger KC, Fontham ETH, Etzioni R (2015) Breast Cancer Screening for Women at Average Risk 2015 Guideline Update From the American Cancer Society JAMA 314: 1599-1614.

- NAPBC responds to USPSTF breast cancer screening recommendations. (2015) American College of Surgeons.

- Arias E (2015) United States life tables, 2010. National vital statistics reports: from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System 63: 1.

- Pace LE, Keating NL (2014) A systematic assessment of benefits and risks to guide breast cancer screening decisions. JAMA 311: 1327-1335.

- Puts MTE, Tapscott B, Fitch M, Howell D, Monette J, et al. (2015) A systematic review of factors influencing older adults’ decision to accept or decline cancer treatment. Cancer Treat Rev 41: 197-215.

- Weiss A, Noorbakhsh A, Tokin C, Chang D, Blair SL (2013) Hormone receptor-negative breast cancer: Undertreatment of patients over 80. Ann Surg Oncol 20: 3274-3278.

- Fisher B, Anderson S, Redmond CK et al. (1995) Reanalysis and results after 12 years of follow-up in a randomized clinical trial comparing total mastectomy with lumpectomy with or without irradiation in the treatment of breast cancer. N Engl J Med 333: 1456- 1461.

- Solin LJ, Schultz DJ, Fowble BL (1995) Ten-year results of the treatment of early-stage breast cancer in elderly women using breast- conserving surgery and definitive breast irradiation. Int J Rad Oncol Biol Phys 33: 535-537.

- Murthy VH, Krumholz HM, Gross CP (2004) Participation in cancer clinical trials: Race-, sex-, and age-based disparities. JAMA 291: 2720-2726.

- Lewis JH, Kilgore ML, Goldman DP (2003) Participation of patients 65 years of age and older in cancer clinical trials. J of Clinic Oncol 21: 1383-1389.

- Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) (2005) Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomized trials. Lancet 365: 1687-1717

- Fisher B, Brown A, Mamounas E (1997) Effect of preoperative chemotherapy on local-regional disease in women with operable breast cancer: Findings from national surgical adjuvant breast and bowel project B-18. J of Clinical Oncol 15: 2483-2493.

- Krag DN, Anderson SJ, Julian TB (2010) Sentinel-lymph-node resection compared with conventional axillary-lymph-node dissection in clinically node-negative patients with breast cancer: Overall survival findings from the NSABP B-32 randomized phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 11: 927-933.

- Hutchins LF, Unger JM, Crowley JJ, Coltman CA, Albain KS (1999) Underrepresentation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer-treatment trials. The New Eng J of Med 341: 2061-2067.

- Muss HB, Berry DA, Cirrincione CT (2009) Adjuvant chemotherapy in older women with early stage breast cancer. The New Eng J of Med 360: 2055-2065

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J (2010) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg 8: 336-41.

- Van Leeuwen BL, Rosenkranz KM, Feng LL, Bedrosian I, Hartmann K et al. (2011) the Department of Surgical Oncology, MD Anderson Cancer Center. The effect of under-treatment of breast cancer in women 80 years of age and older. Critical Rev in Oncol /Hematol 79: 315-320.

- Rosenkranz KM, Bedrosian I, Feng L (2006) Breast cancer in the very elderly: Treatment patterns and complications in a tertiary cancer center. Am J Surg 192: 541-544.

- Angarita FA, Chesney T, Elser C, Mulligan AM, McCready DR, et al. (2015) Treatment patterns of elderly breast cancer patients at two canadian cancer centres. Eur J Surg Oncol 41: 625-634.

- Besic N, Besic H, Peric B (2014) Surgical treatment of breast cancer in patients aged 80 years or older-how much is enough? BMC Cancer 14:700.

- Bouchardy C, Rapiti E, Fioretta G (2003) Undertreatment strongly decreases prognosis of breast cancer in elderly women. J Clin Oncol 21: 3580-3587.

- Chatzidaki P, Mellos C, Briese V, Mylonas I (2011) Perioperative complications of breast cancer surgery in elderly women >/=80 years). Ann Surg Oncol 18: 923-931.

- Cortadellas T, Gascon A, Cordoba O2013) Surgery improves breast cancer-specific survival in octogenarians with early-stage breast cancer. Int J Surg 11: 554-557.

- Cyr A, Gillanders WE, Aft RL, Eberlein TJ, Margenthaler JA (2011) Breast cancer in elderly women (>/= 80 years): Variation in standard of care? J Surg Oncol 103: 201-206.

- Dialla PO, Dabakuyo TS, Marilier S (2012) Population-based study of breast cancer in older women: Prognostic factors of relative survival and predictors of treatment. BMC Cancer. 12:472.

- Evron E, Goldberg H, Kuzmin A (2006) Breast cancer in octogenarians. Cancer 106: 1664-1668.

- Guth U, Myrick ME, Kandler C, Vetter M (2013) The use of adjuvant endocrine breast cancer therapy in the oldest old. Breast 22: 863-868.

- Joerger M, Thurlimann B, Savidan A (2013) Treatment of breast cancer in the elderly: A prospective, population-based swiss study. J Geriatr Oncol 4: 39-47.

- Litvak DA, Arora R. (2006) Treatment of elderly breast cancer patients in a community hospital setting. Arch Surg 141:90.

- Mery B, Assouline A, Rivoirard R (2014) Portrait, treatment choices and management of breast cancer in nonagenarians: An ongoing challenge. Breast 23: 221-225.

- Morishita Y, Tsuda H, Fukutomi T, Mukai K, Shimosato Y, et al. (1997) Clinicopathological characteristics of primary breast cancer in older geriatric women: A study of 39 japanese patients over 80 years old. Jpn J Cancer Res 88: 693-699.

- Strader LA, Helmer SD, Yates CL, Tenofsky PL (2014) Octogenarians: Noncompliance with breast cancer treatment recommendations. Am Surg 80: 1119-1123.

- Vetter M, Huang DJ, Bosshard G, Guth U (2013) Breast cancer in women 80 years of age and older: A comprehensive analysis of an underreported entity. Acta Oncol 52: 57-65.

- Aapro MS. (2002) Progress in the treatment of breast cancer in the elderly. Ann Oncol 13: 207-210.

- Balducci L, Extermann M, Carreca I (2001) Management of breast cancer in the older woman. Cancer Control 8: 431-441.

- Extermann M, Balducci L, Lyman GH (2000) What threshold for adjuvant therapy in older breast cancer patients? J Clin Oncol 18: 1709-1717.

- Bouchardy C, Rapiti E, Blagojevic S, Vlastos AT, Vlastos G (2007) Older female cancer patients: Importance, causes, and consequences of undertreatment. J Clin Oncol 25: 1858-1869.

- Hughes KS, Schnaper LA, Bellon JR, Cirrincione CT, Berry DA, et al. (2013) Lumpectomy plus tamoxifen with or without irradiation in women age 70 years or older with early breast cancer: long-term follow-up of CALGB 9343. J of Clinic Oncol 31: 2382-2387.

Relevant Topics

- Advances in Breast Cancer Treatment

- Alternative Treatments for Breast Cancer

- Breast Cancer Biology

- Breast Cancer Cure

- Breast Cancer Grading

- Breast Cancer Prevention

- Breast Cancer Radiotherapy

- Breast Cancer Research

- Breast Cancer Therapeutic & Market Analysis

- Breast Screening

- Cancer stem cells

- Fibrocystic Breast

- Hereditary Breast Cancer

- Inflammatory Breast Cancer

- Invasive Ductal Carcinoma

- Making Strides in Breast Cancer

- Mastectomy

- Metastatic Breast Cancer

- Molecular profiling

- Radiotherapy for Breast Cancer

- Smoking in Breast Cancer

- Terminal Breast Cancer

- Tumor biomarkers

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 18861

- [From(publication date):

December-2016 - Aug 23, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 17841

- PDF downloads : 1020